Appendicitis - Pitfalls in US and CT diagnosis

Julien Puylaert and Julie Tutein Nolthenius

HMC, the Hague and Amsterdam UMC; East Kent Hospitals, Canterbury, UK

Publicationdate

In this chapter we will deal with the optimal diagnostic strategy in patients with suspected appendicitis, and the pitfalls leading to a false-positive or false-negative diagnosis.

Special attention will be given to:

- Abnormal location of the appendix

- Differential diagnosis of appendicitis

- Complications.

For critical comments and additional remarks: [email protected]

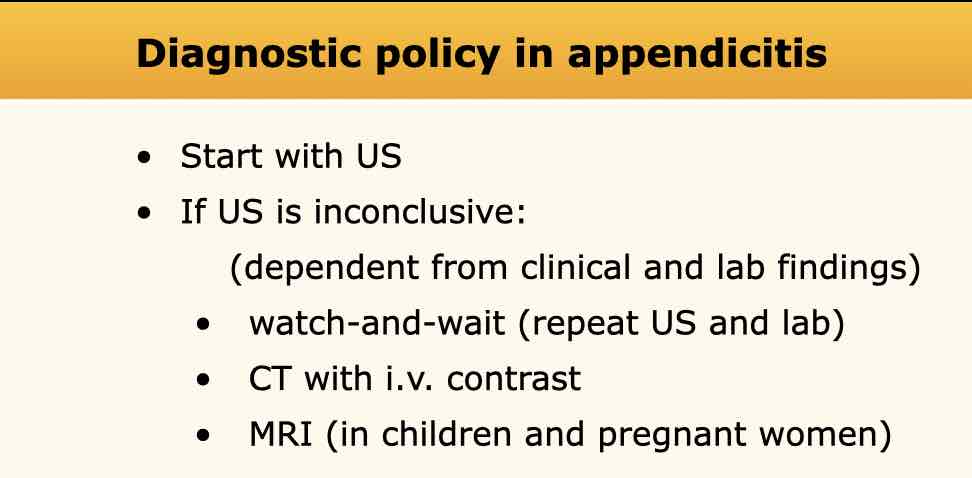

Diagnostic strategy in suspected appendicitis

The policy in patients with an acute abdomen in the Netherlands has a well-established scientific basis (Table) (Lameris et al. BMJ 2009;338: b2431).

CRP and WBC as well as clinical impression, play an important role in choosing between complementary CT scan and watchful waiting.

First US, than CT.

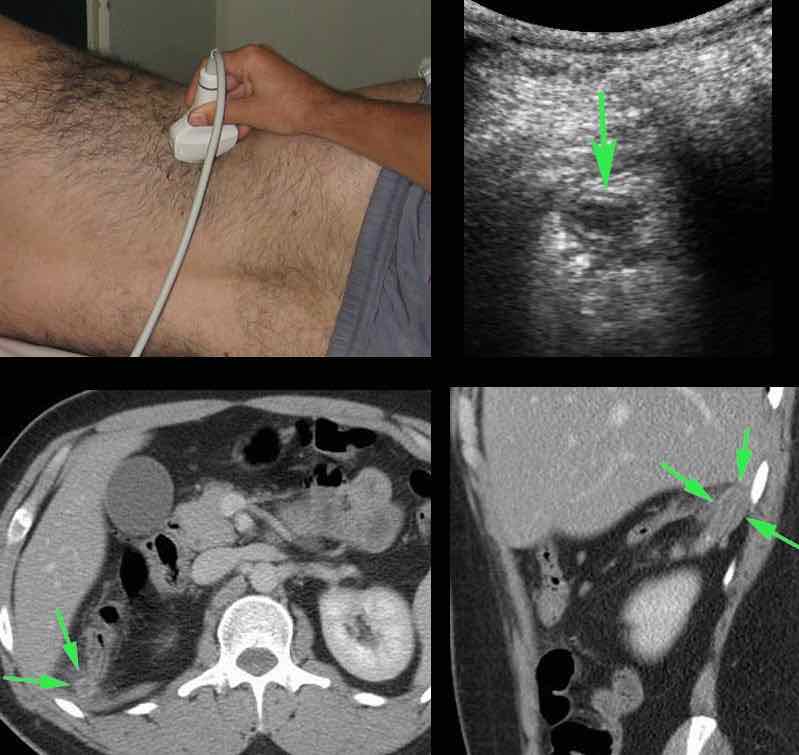

Patients with suspected appendicitis are relatively young, and it seems reasonable to begin with US in most patients.

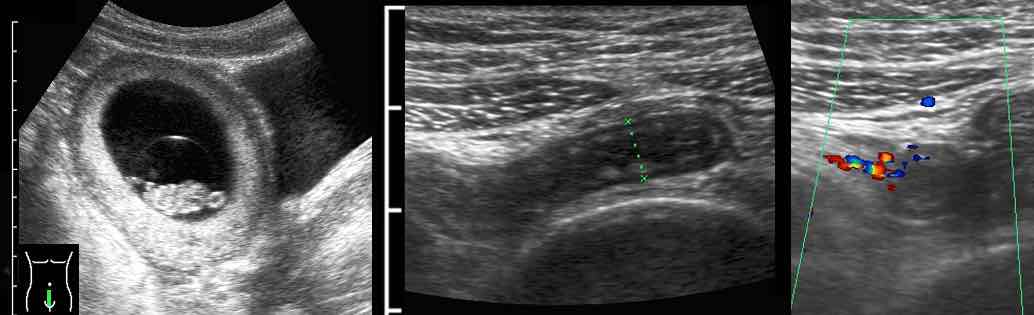

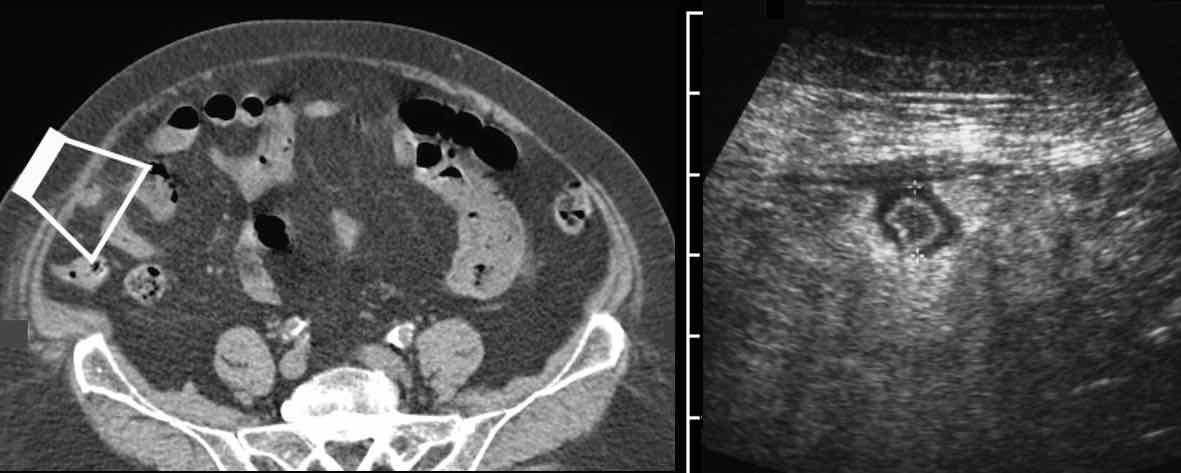

In this 11-week pregnant woman, US confirmed an intact intra-uterine pregnancy as well as acute appendicitis.

Note the different cm-scales.

Laparoscopic removal of the inflamed appendix was successful.

CT if inconclusive US

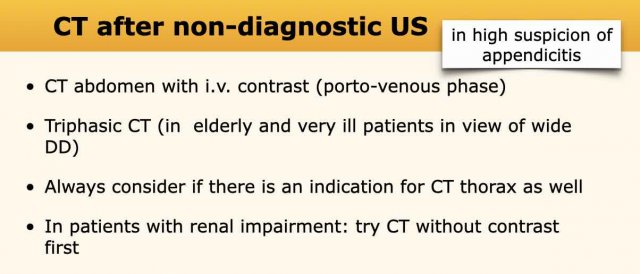

In most patients with an inconclusive US and a high suspicion of appendicitis, CT is the next step.

A fortunate circumstance for CT, is that these patients are often obese.

CT is principally performed with i.v. contrast.

If there is serious pain in elderly patients with a wide differential diagnosis, triphasic CT and even CT-thorax, can be added.

In our hospital of all patients who undergo CT for acute abdomen, in about 15 % a CT thorax is ordered within 24 hours, and vice versa.

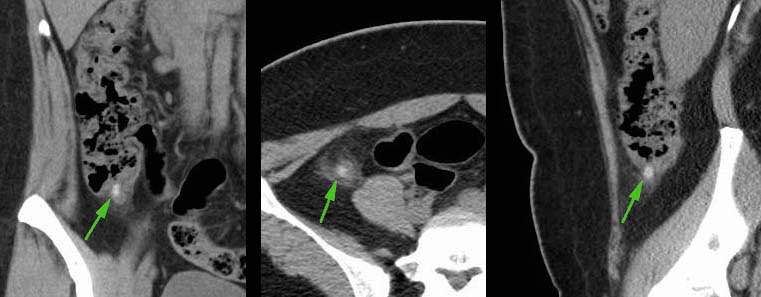

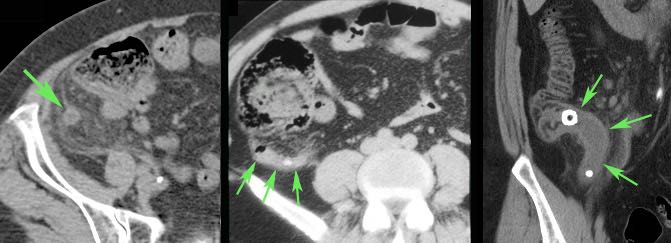

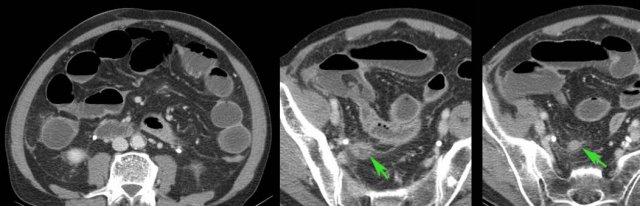

In case of renal impairment, CT without contrast may be diagnostic as in these three patients.

If CT without contrast is non-diagnostic, repeat CT with iv contrast after correction of renal function.

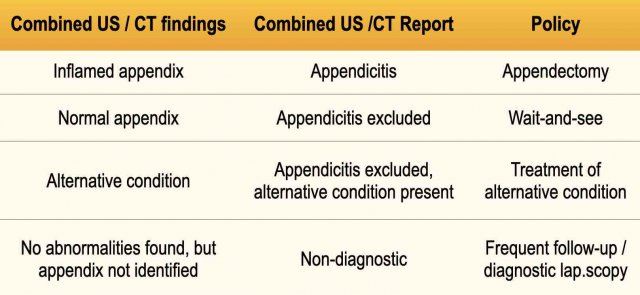

When both US and CT are done, it is important to integrate US and CT findings into a combined report.

The combination of US with optional CT, is highly accurate for appendicitis, and is inconclusive in less than 1% of high-suspicion patients (maybe 2 to 3 patients per year in our hospital).

Repeat US and/or CT and also diagnostic laparoscopy are then helpful.

First CT than US

When for some reason CT scan is chosen as primary investigation, US after CT can also be useful.

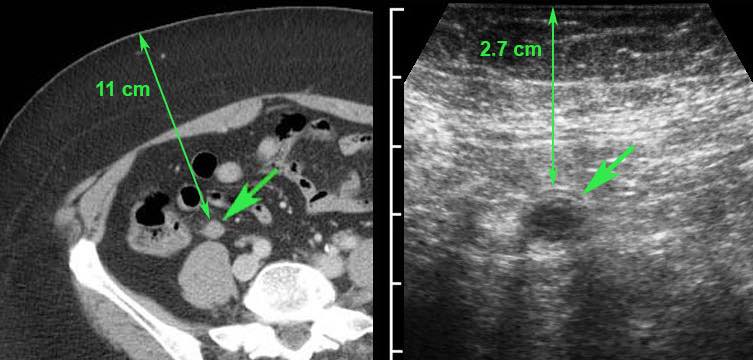

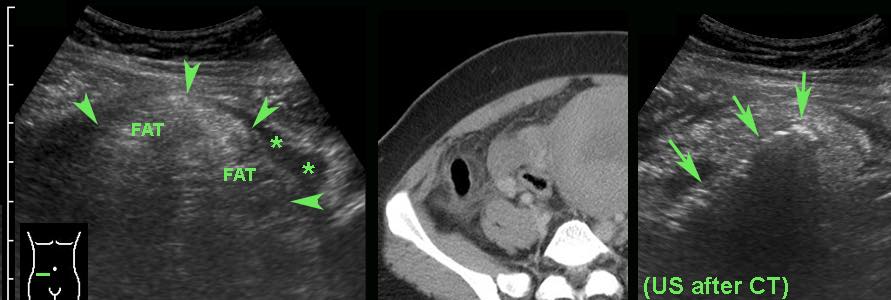

In this elderly lady with atypical abdominal pain and renal insufficiency, a non-contrast CT revealed a dubiously inflamed appendix.

Focused US with a high-frequency probe confirmed that the ventrally located appendix was inflamed.

In this obese patient, CT identified a deeply located, possibly inflamed appendix (arrow) at a distance of 11 cms from the skin.

Focused US with graded compression reduced this distance to < 3 cms, allowing the use of a high frequency probe, which showed a non-compressible, inflamed appendix (arrow).

In this young man the appendix could not be identified on CT scan due to lack of intra-abdominal fat.

US easily demonstrated a normal appendix.

False-negative diagnosis

US non-visualization of the appendix: tricks and tips

The most important reason for a false-negative ultrasound examination is overlooking the inflamed appendix.

The greatest problem is non-visualization of the appendix. In adult patients, the numbers are as follows (Table).

In experienced hands the inflamed appendix can be visualized in 80-90% of patients with acute appendicitis.

Hereunder the pitfalls leading to non-visualization and how to avoid them.

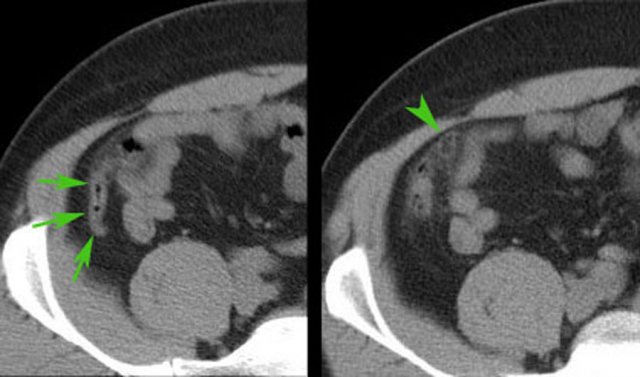

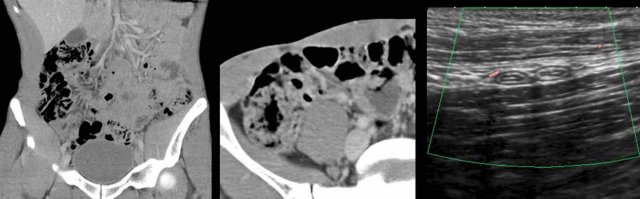

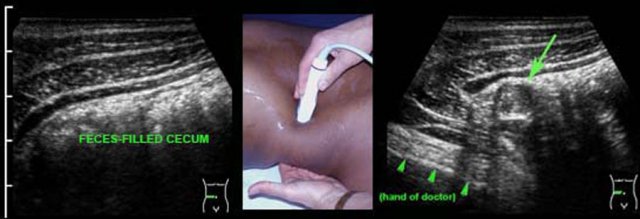

Retrocecal appendicitis

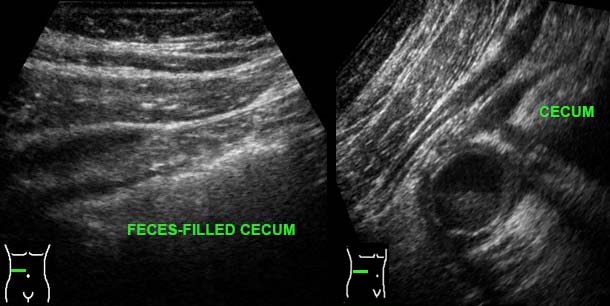

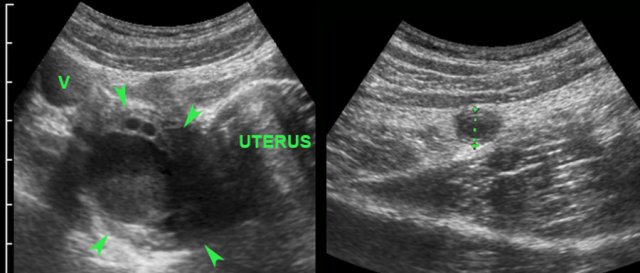

The appendix is usually found at the spot of maximum tenderness.

In retrocecal appendicitis (arrow) the cecum is often pushed medially with the US probe, so that the appendix (arrow) appears to be localized lateral to the cecum than behind it.

Another possibility to visualize the appendix in retrocecal appendicitis is positioning of the probe in the right flank, thereby avoiding the gas and feces-filled cecum.

Another trick in retrocecal appendicitis is to push the inflamed appendix (arrow) with your left hand in the direction of the probe.

To find the appendix, it may be useful at first to identify the ileocecal valve (see also US of the GI tract: normal anatomy).

The base of the appendix is usually found 3 centimeters caudally, where it leaves the cecal pole at the medial side.

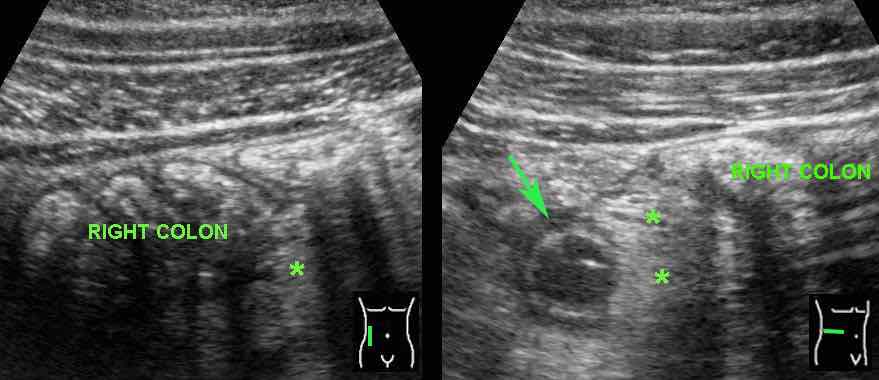

The biggest problem for US is a deep pelvic location of the appendix.

In this pregnant, obese woman, a possible inflamed appendix (arrow with question mark) was visualized during forceful compression deep down in the pelvis.

Subsequent transvaginal US showed a pus-filled, inflamed appendix within 1 cm of the vaginal probe.

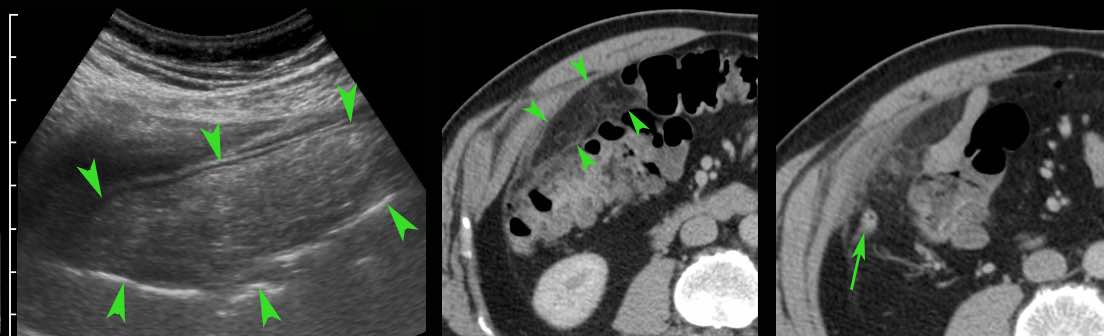

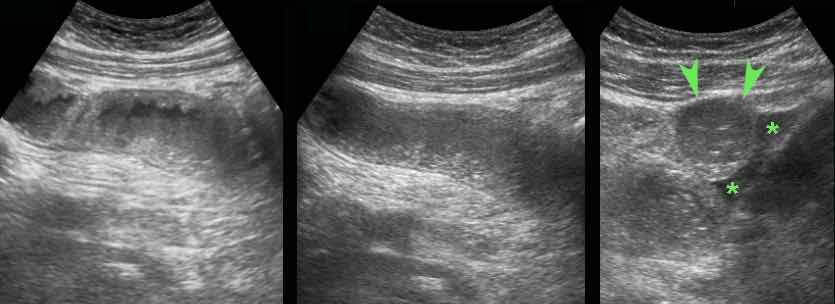

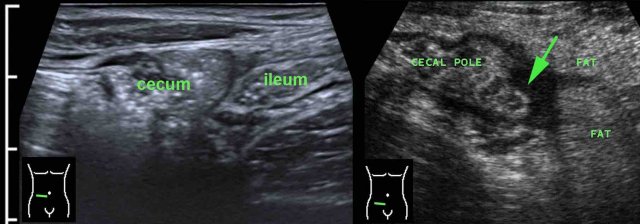

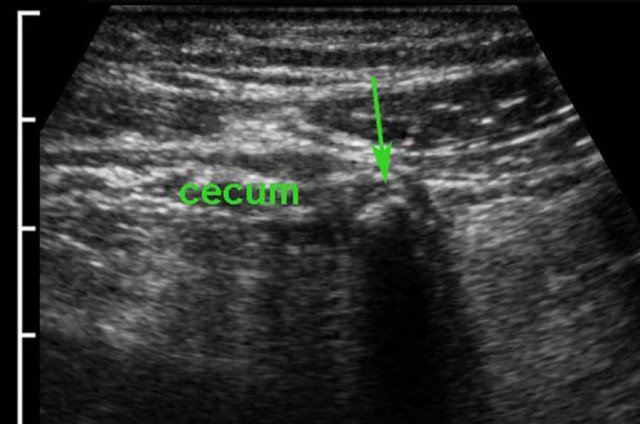

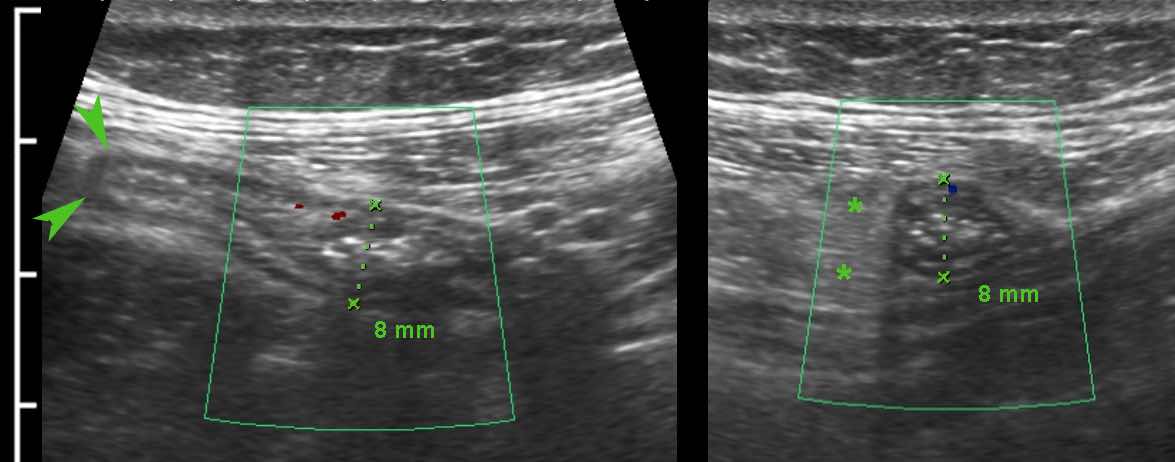

Air in the lumen can make it difficult to identify the inflamed appendix (arrowheads).

The echolucent wall and the surrounding inflamed fat (*), make clear that appendicitis is present.

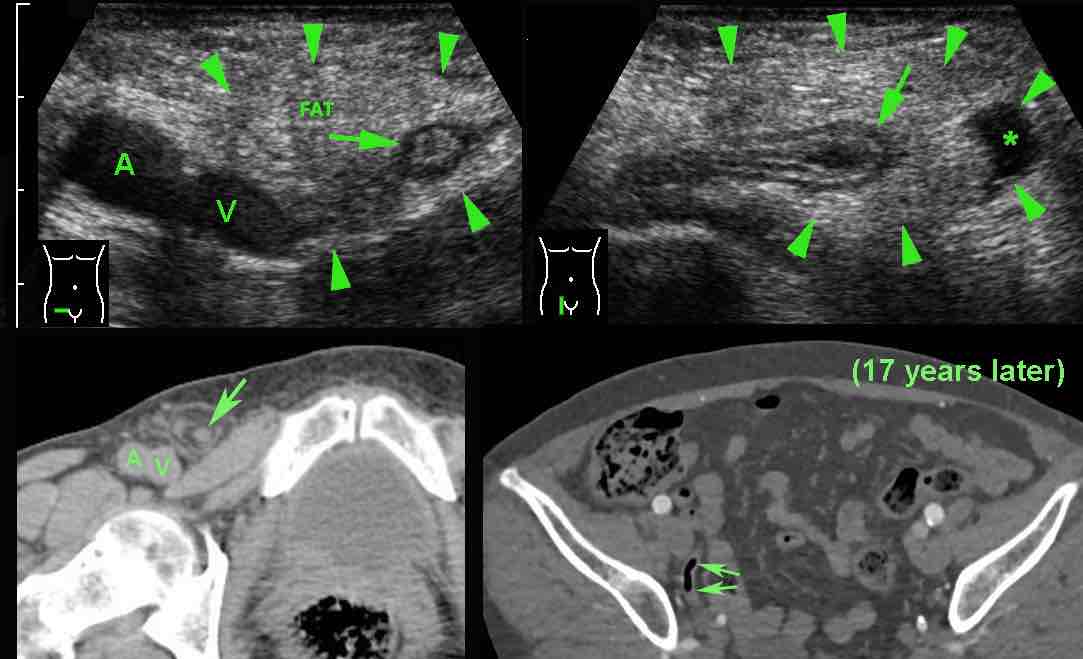

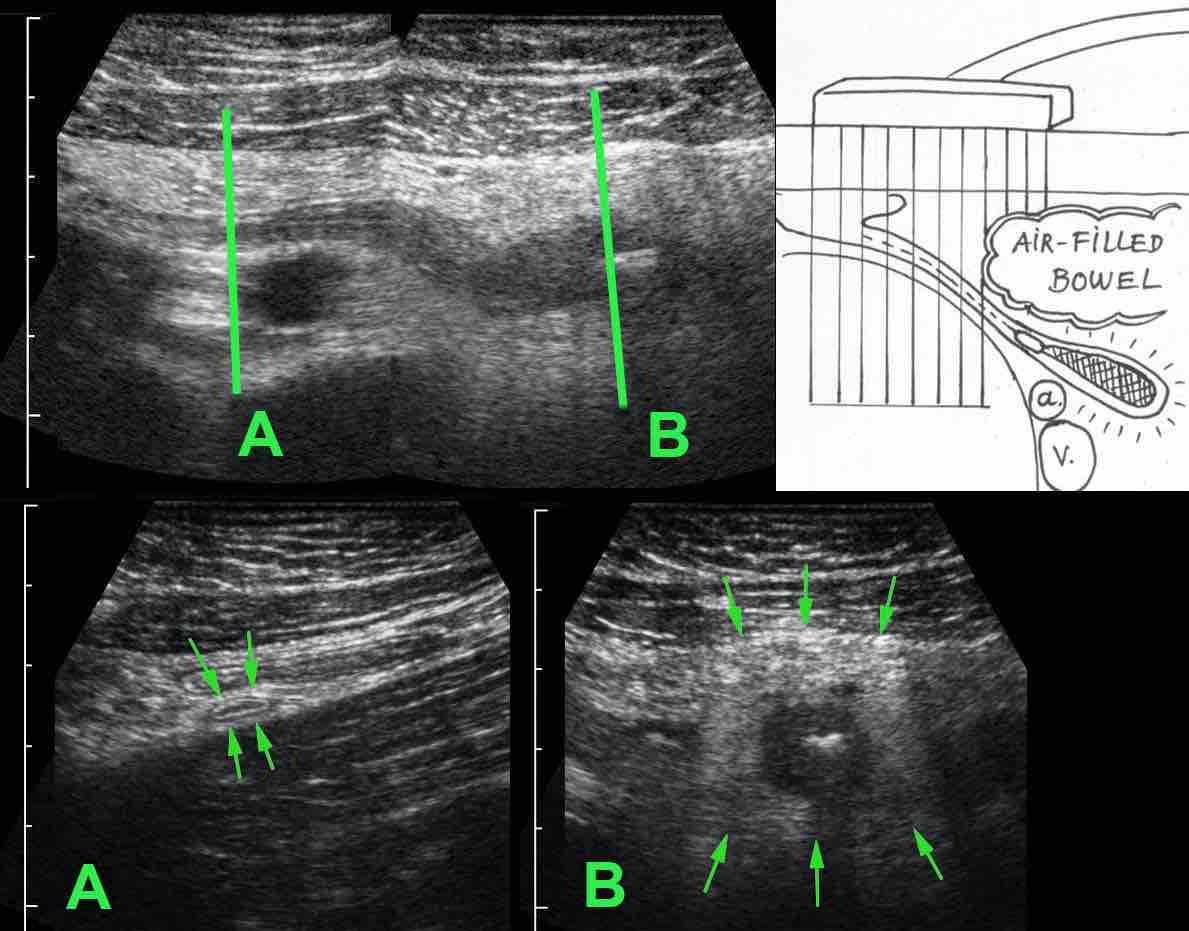

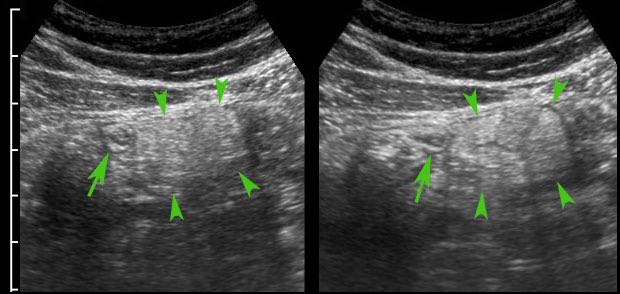

Another pitfall is tip-appendicitis, where the inflammation is confined to the distal tip.

If only the normal, proximal part (arrows in A) is visualized, and the distal end (arrows in B) would have been obscured by bowel gas, a false-negative diagnosis may be the result. (a and v = iliac artery and vein)

The presence of a generalized, paralytic ileus is suspect for perforated appendicitis, and if the inflamed appendix cannot be visualized, CT is mandatory, also to exclude other conditions.

This 66-year old man presented with excruciating abdominal pain with generalized peritonitis and a CRP of 550.

US revealed only dilated small bowel, CT was done for suspected mesenteric ischemia.

CT demonstrated appendicitis (arrow) with a perforated tip and four-quadrant contamination of the peritoneal cavity.

Mistaking an inflamed appendix for a normal appendix

In 7 % of patients with appendicitis, the inflamed appendix has a US diameter of less than 7 mm.

If there is hypervascularity and inflamed fat and the patient has mild symptoms, this is usually a case of spontaneously resolving appendicitis (see Appendicitis: US findings).

This young man had a rapidly subsiding symptoms at the time of US, with CRP 1 and WBC 9.

Surgery was nevertheless performed and histology confirmed ordinary, acute appendicitis.

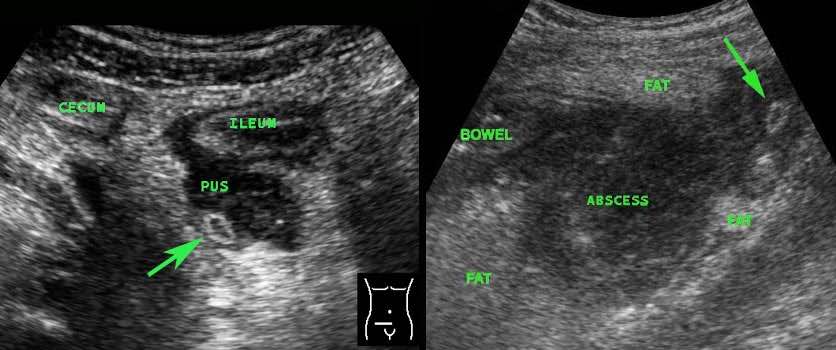

In advanced appendicitis, the inflamed appendix (arrow) may have a very small diameter, because it has emptied itself into an abscess.

In these two cases, the secondary US findings of puscollections and inflamed fat, give away the correct diagnosis.

Incorrect diagnosis of an alternative condition

In some patients, US findings may suggest an alternative condition, while in fact appendicitis is present.

This is obviously a dangerous pitfall.

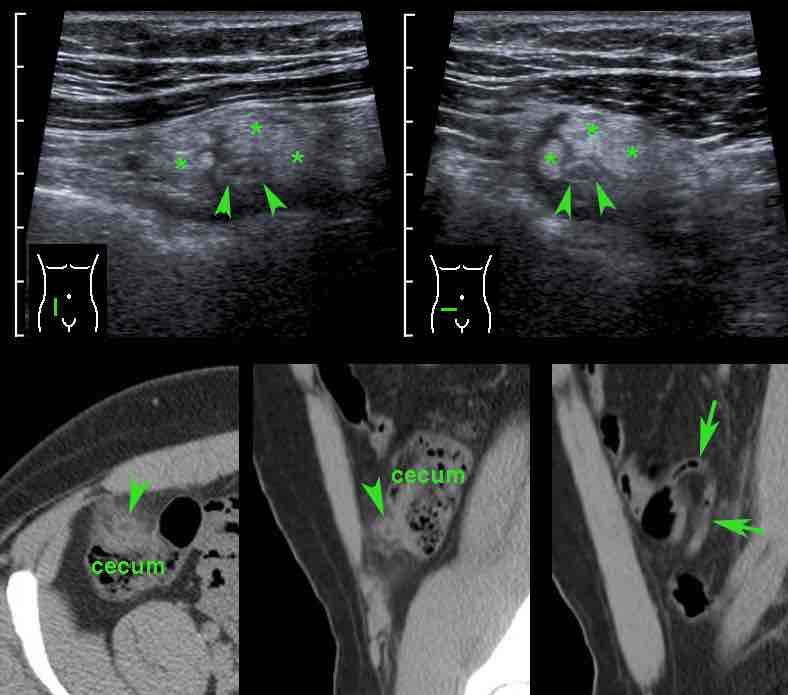

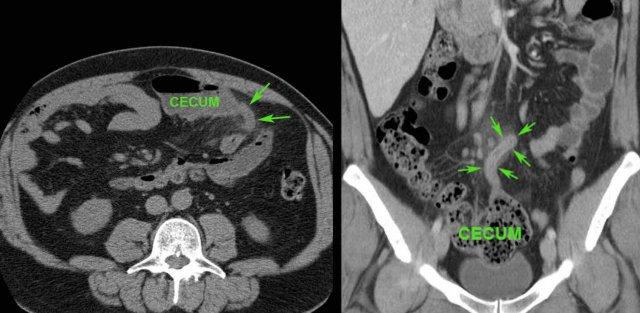

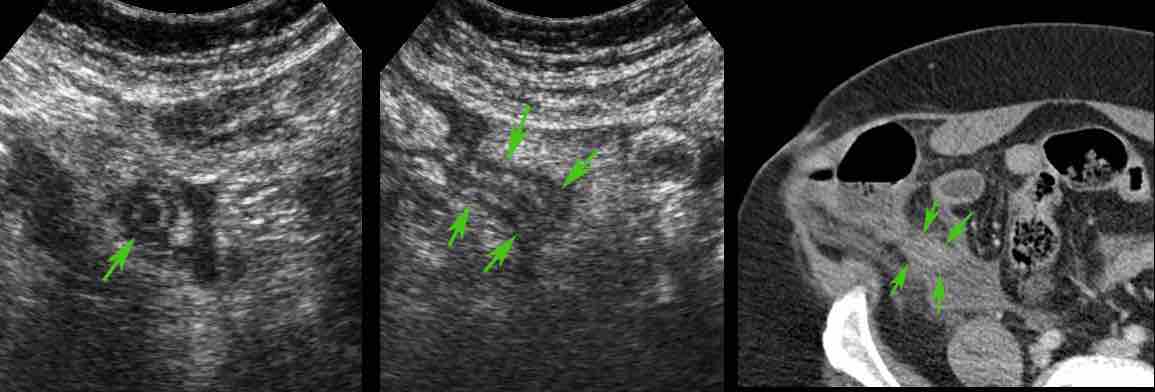

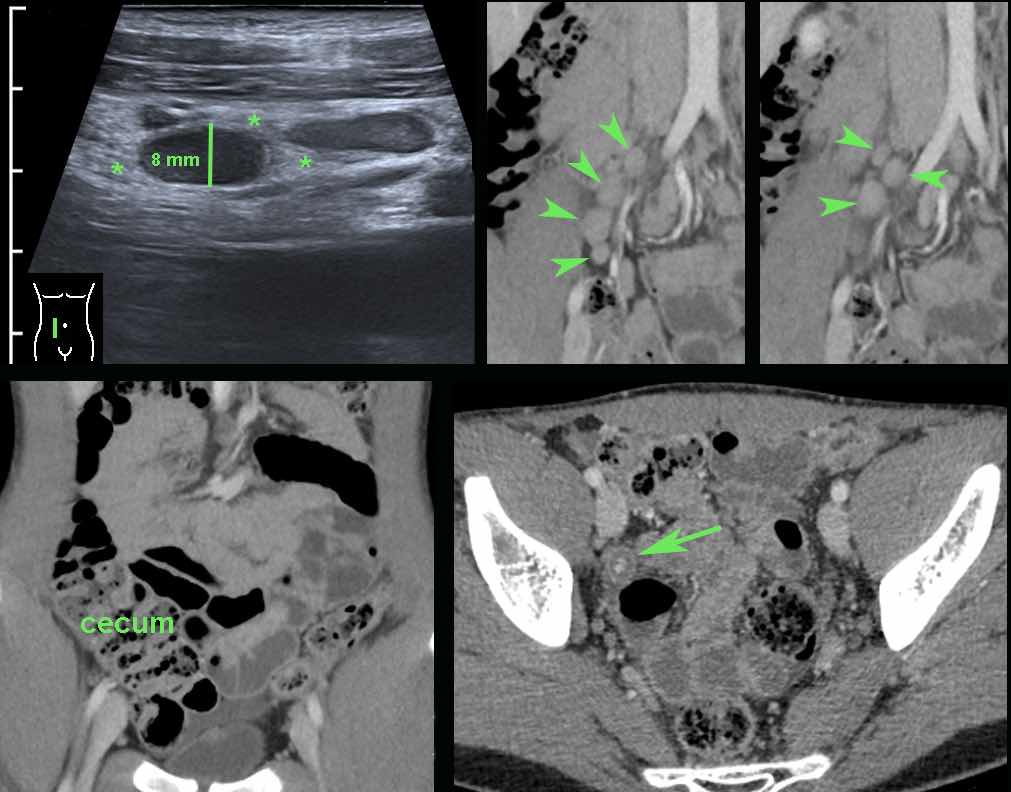

In this 16 year old patient with RLQ pain, enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes surrounded by some inflamed fat (*) were the only US finding and the appendix could not be identified.

CT confirmed the enlarged nodes (arrowheads), but revealed an inflamed appendix (arrow), originating from the cecum in deep pelvic position.

Young patients with acute appendicitis often have secondarily enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes.

Mesenteric lymphadenitis

If enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes are the only US findings in a young patient with RLQ pain, the diagnosis of viral mesenteric lymphadenitis can be considered.

It is however mandatory to identify the normal appendix (arrow) with certainty, because enlarged nodes can be secondary to appendicitis.

Infectious ileocecitis / ileocolitis

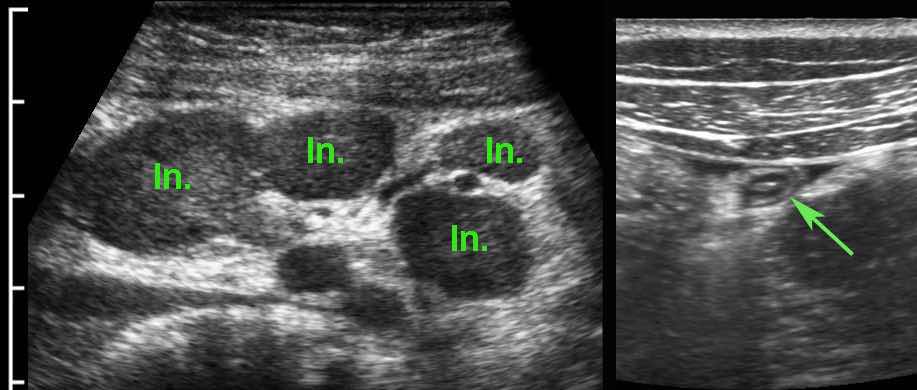

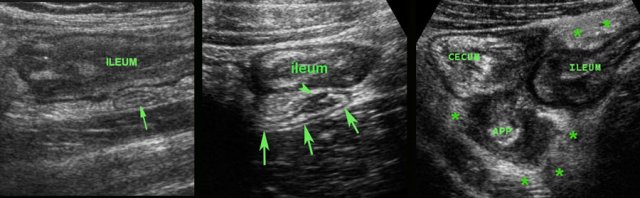

Another pitfall is when secondary wall thickening of ileum or right colon is visualized, but the underlying appendicitis is overlooked.

In this patient initially the submucosal colonic wall thickening was interpreted as infectious ileocolitis by Campylobacter or Salmonella.

Positioning of the probe in the right flank, revealed the inflamed appendix (arrow) surrounded by inflamed fat (*).

The presence of inflamed fat in itself is a key finding, because this is never found in infectious colitis.

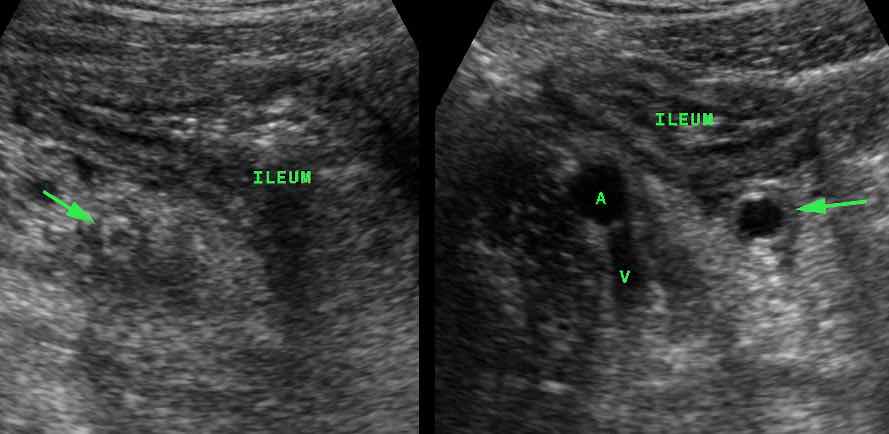

Appendicitis (arrow) causing secondary thickening of the neighboring ileum.(A and V= iliac artery and vein)

Appendicitis (arrow) causing secondary thickening of the neighboring ileum.(A and V= iliac artery and vein)

In these two patients initially the mucosal thickening of the terminal ileum as a sole US finding was interpreted as Crohn’s ileitis or infectious ileitis.

A second US exam revealed the underlying appendicitis (arrow) causing secondary thickening of the neighboring ileum.

Right ovarian cyst

Another pitfall is the erroneous diagnosis of an alternative gynecological condition, while in fact appendicitis is present.

In this young woman, a conspicuous hemorrhagic right ovarian cyst (arrowheads) was visualized and held responsible for her RLQ symptoms.

Further searching however revealed acute appendicitis, the cyst being a confusing coincidental finding.

Cecal diverticulitis

In this young man a fecolith (arrow) attached to the cecum was interpreted as cecal diverticulitis.

He was initially treated conservatively but after 24 hours his symptoms deteriorated and he was operated.

At surgery a perforated appendicitis was found with a fecolith in its base.

In this case, CT scan would certainly have made this important differential diagnosis.

Epiploic appendagitis

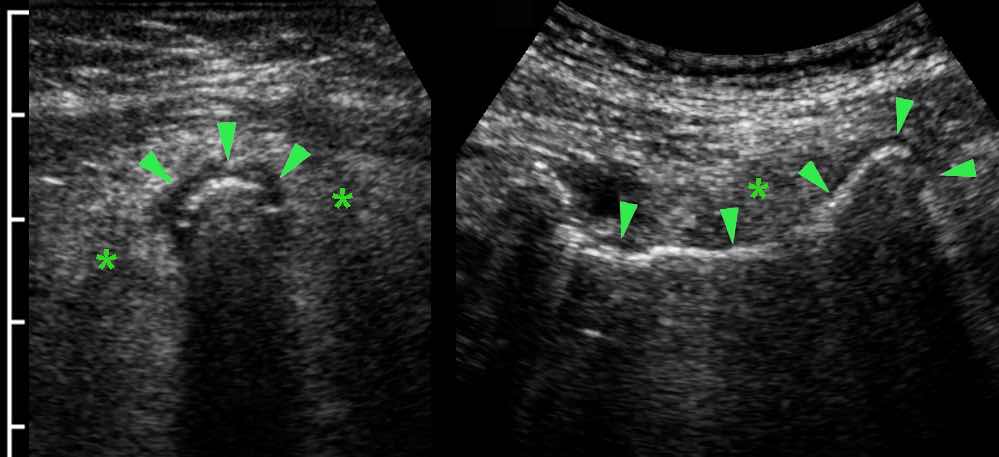

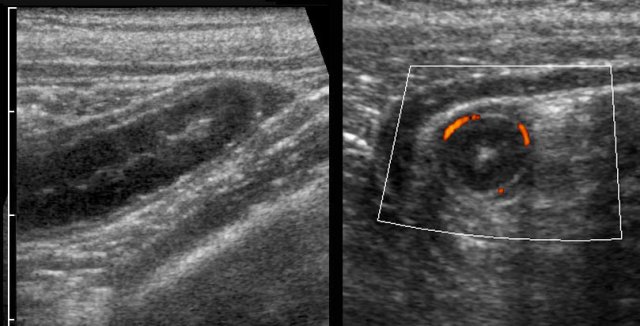

In this obese young woman, US initially showed only a large mass of inflamed fat (arrowheads), surrounded by some fluid (*).

This was interpreted as epiploic appendagitis or omental infarction.

Subsequent CT revealed a gas-filled inflamed appendix, surrounded by fat stranding.

Repeated US after the CT was able to identify the air-filled appendix (arrows).

False-positive US diagnosis

In young children, the normal appendix may be large due to very prominent lymphoid hyperplasia of the deep mucosa.

In this 6-year old, asymptomatic child a large appendix was seen.

Notice that you can identify the normal anatomical layers of the appendix.

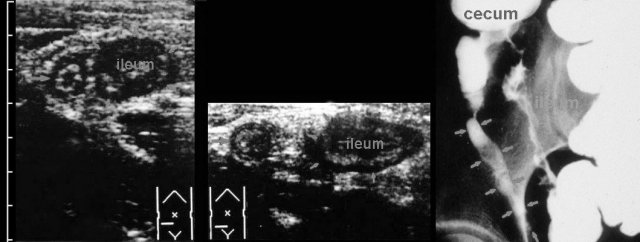

Crohn’s disease

Mistaking a normal for an inflamed appendix may also occur if there is secondary thickening of the appendix associated with another condition.

These images, though 30 years old, are still illustrative.

In this young man with suspected appendicitis both ileum and appendix (arrow) were thickened, due to ileocecal Crohn disease, also affecting the appendix.

Barium study confirms Crohn ileitis and shows irregular filling of the appendix, proving that this is a case of non-obstructive Crohn appendicitis.

Variable involvement of the appendix (arrow) in ileocecal Crohn disease:

- No involvement (left),

- Slight involvement (arrowhead) (middle)

- Severe involvement, with abundant inflamed fat * (right)

This patient with pain RLQ, had a complicated appendectomy with abscess formation 4 years earlier, with intermittent symptoms afterwards.

Now US shows a Crohn ileitis with a fistula (*) in the direction of the cecal pole.

CT and bariumstudy confirm Crohn ileitis (arrowheads) and a fistula (arrow) from the ileum to the cecal pole.

After ileocecal resection, he remained symptom free for at least 15 years.

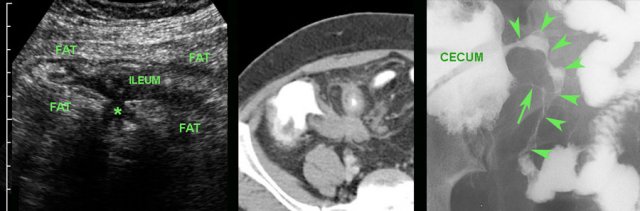

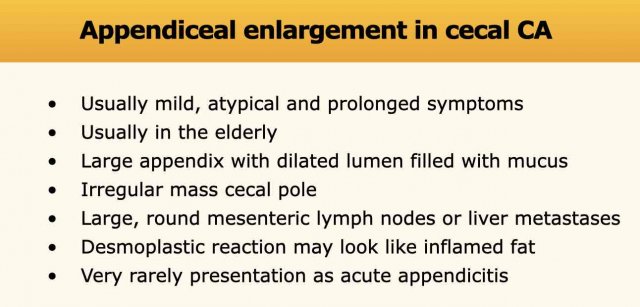

Cecal carcinoma

In cecal carcinoma, atypical clinical findings may lead to serious delay, because the erroneous diagnosis of “appendiceal mass” is made.

US and CT findings may add to the confusion, by showing mucinous dilatation of the appendix due to obstructive ingrowth of tumour in the appendix base.

Tumour-based obstruction rarely leads to full-blown appendicitis.

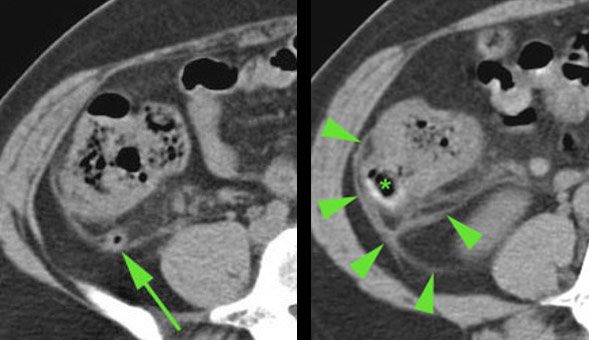

This is a 79-year old woman with vague RLQ pain since six weeks.

Normal lab.

CT shows a large cecal carcinoma with mucinous dilatation of the appendix.

No fat stranding.

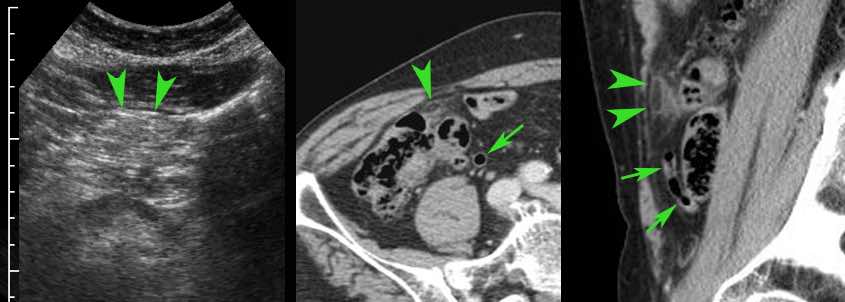

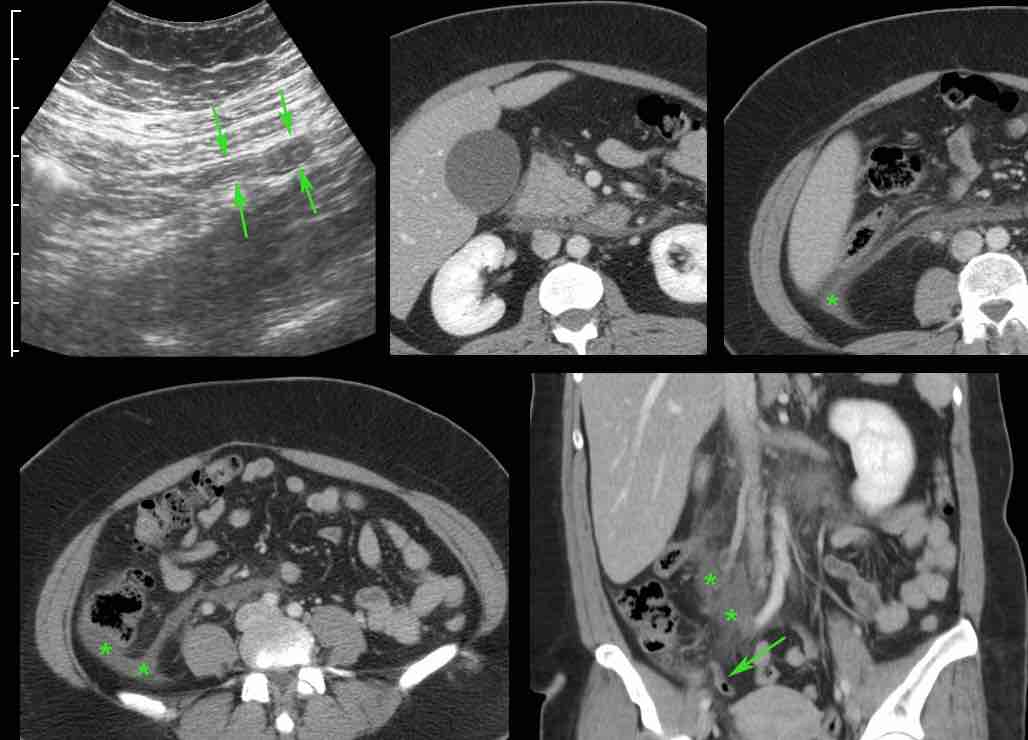

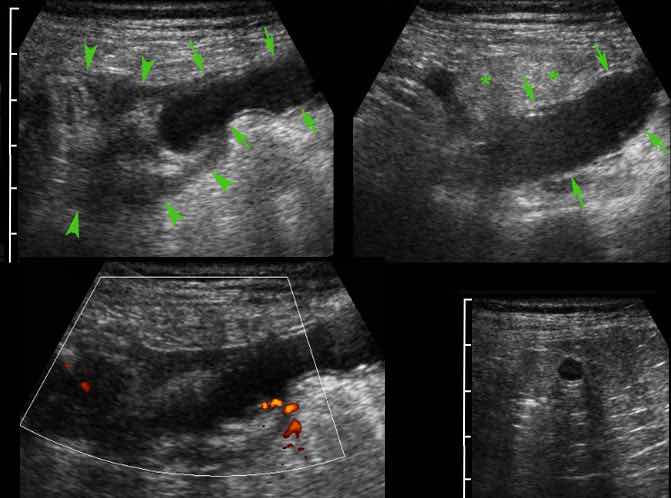

A 73-year old man presents with three weeks of nagging pain in the RLQ and a CRP of 45.

US finds a large appendix (arrows) with mucinous dilatation of the lumen and relatively little inflamed fat (*).

The cecal pole has an irregularly thickened wall with increased vascularization.

There is one small, but remarkably round local lymph node.

The combined clinical and US findings are suspect for cecal carcinoma invading the base of the appendix.

A patient with a dilated appendix (arrow) due to a cecal carcinoma invading the base of the appendix.

This caused protracted and atypical pain symptoms and not full-blown appendicitis.

Cecal diverticulitis

In this patient young patient with cecal diverticulitis the most prominent fat stranding (arrowheads) is found around a cecal diverticulum, containing a fecolith (*).

The appendix (arrow) is secondarily inflamed due to the nearby cecal diverticulitis.

Complete cure with conservative treatment.

Normal appendix mistaken for appendicitis

A false positive diagnosis can be made if the normal appendix is mistaken for an inflamed one.

Of all normal appendices, 7 % is larger than 7 mm (see US of the GI tract).

Clinical presentation and the presence / absence of inflamed fat are the most decisive features.

In doubtful cases like in this patient in whom an 8 mm appendix with dubious inflamed fat (*) was visualized including the blind end (arrowheads), clinical follow-up and repeated US the next day is a safe policy.

Try to convince the surgeon, that an appendix like this will not rupture overnight.

If the patient is painful with a high CRP, CT should be the next step, especially to exclude other conditions.

Epiploic appendagitis

This 39-year old man had 24 hours of pain in the RLQ with severe local peritonitis, clinically very suspect for acute appendicitis.

He had an important business flight to Taiwan the next morning.

US shows a 7 mm not well compressible appendix (arrow) with inflamed fat (arrowheads), which was located medially, rather than surrounding the appendix.

Continue with next images...

During intermittent graded compression, the inflamed fat could be pushed away from the appendix.

Click image for animation.

Continue with next images...

CT confirmed a normal appendix surrounded by normal fat and an adjacent, a small epiploic appendagitis (arrowhead).

He was reassured, was given painkillers and caught his flight to Taiwan the next morning.

This patient also underlines the observation that, in epiploic appendagitis, there is no relation between size and the degree of local peritonitis.

So, in epiploic appendagitis size does not matter.

This 41-year old male had severe local peritonitis in the RLQ.

The longitudinal US image showed a concentrically layered ovoid structure (arrowheads) surrounded by inflamed fat (*), suggestive for an inflamed appendix.

In the transverse plane however the US image structure was also ovoid (arrowheads).

Subsequent CT scan demonstrated that the ovoid structure in fact was a small infarcted epiploic appendage.

CT also identified the normal appendix (arrows).

This was a 73-year old lady with severe RLQ pain, CRP and a local, not well described area of inflamed fat (arrowheads).

CT confirmed a small epiploic appendagitis (arrowheads) and a normal appendix (arrows).

Again, no relation between local pain symptoms and size of the infarcted epiploic appendage.

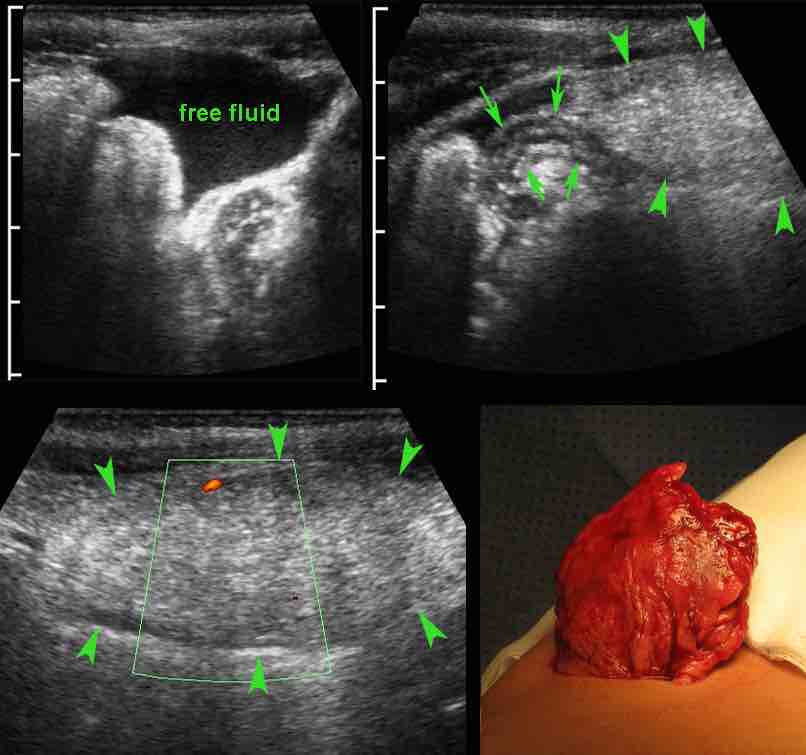

Omental infarction

Images of a 6-year old boy with three days of progressive painin the RLQ, WBC 11 and CRP 80.

US showed free fluid, a normal sized appendix (arrows) and a large mass of inflamed fat (arrowheads) with minimal peripheral vascularization.

Clinical and US features were erroneously interpreted as possible perforated appendicitis.

At surgery a normal appendix was removed as well as a firm mass originating from the omentum.

Diagnosis: segmental omental infarction.

This condition should have been treated conservatively.

Images of a previously healthy 50 years old man, who experienced progressive pain right of the umbilicus.

Lab: WBC 10, CRP 33.

Appendicitis was suspected.

US showed large, cake-like mass of inflamed fat (arrowheads) with ventrally, echolucent thickening of the peritoneum.

The appendix was not identified.

CT confirmed omental infarction (arrowheads) and a normal appendix (arrow), surrounded by some fat stranding, associated with the omental infarction.

Recovery without treatment.

Acute pancreatitis

Many other conditions may cause secondary thickening of the appendix.

Detection of the underlying condition by US or CT is then mandatory.

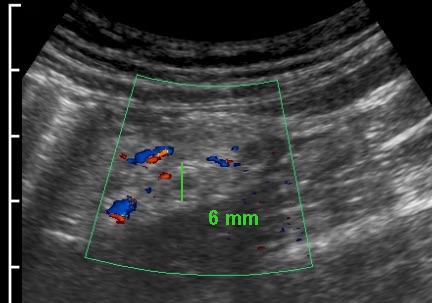

This obese lady presented with RLQ pain, a CRP of 80 and a normal serum amylase.

US identified a 6 mm appendix (arrows) with severe local tenderness.

CT scan revealed acute pancreatitis with retroperitoneal fluid (*) descending to the RLQ, explaining the patient’s symptoms mimicking appendicitis.

The pancreatic exudate (*) approaches the appendix (arrow) closely.

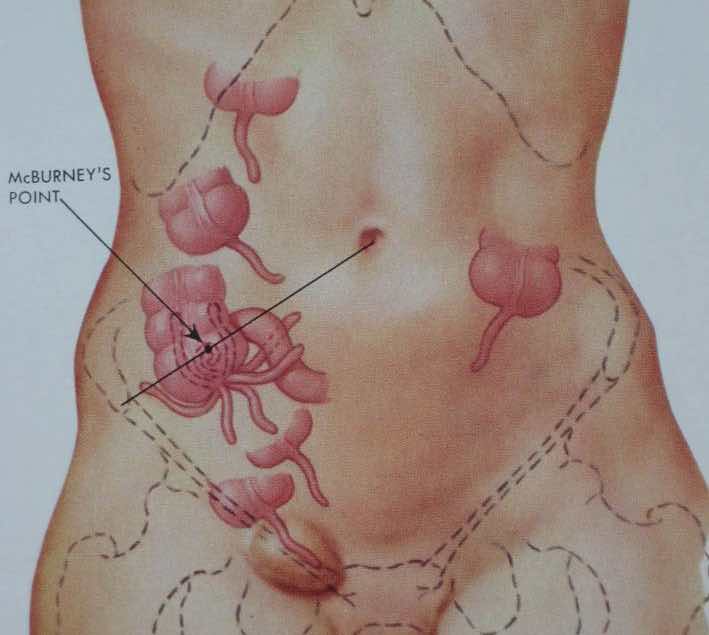

Abnormal location of the appendix

The appendix base most often lies near McBurney’s point.

However there is a wide variation in location of the cecum and also in the orientation of the appendix (figure).

An inguinal hernia containing the appendix, is named Amyand hernia.

A Garengeot hernia is an appendix in a femoral hernia.

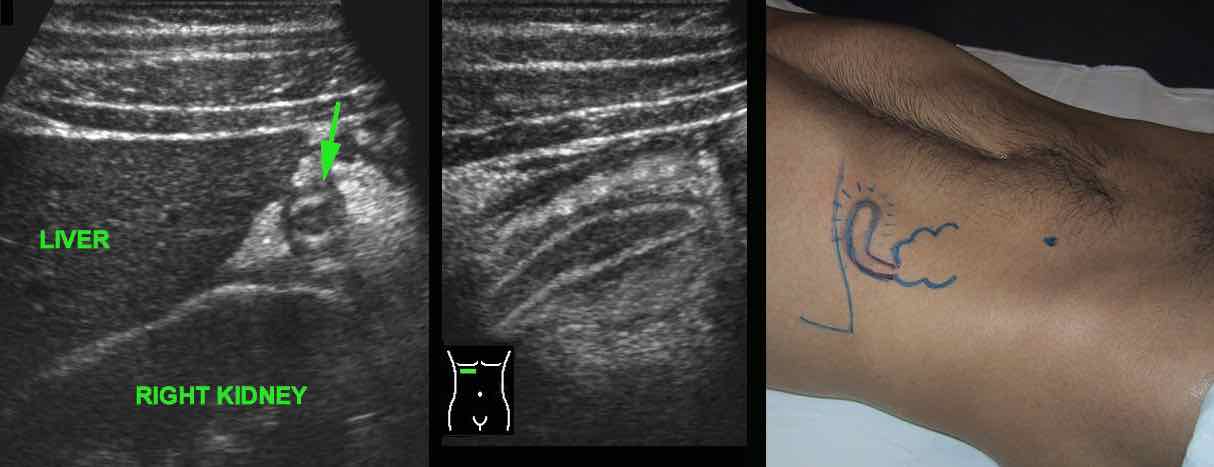

In case of an abnormal position of the inflamed appendix far from McBurney’s point, it is useful to indicate the location of the appendix on the skin with a waterproof pencil.

This may influence site, size and orientation of the incision and also the choice for laparoscopic appendectomy.

In this 30-week pregnant lady with early appendicitis (arrow), the drawing enabled the surgeon to perform a small incision, exactly over the appendix base.

In this young man the acute RUQ pain was explained by an inflamed appendix (arrow) in unusual high position.

Note the distance from McBurney’s point (dot).

The appendix was laparoscopically removed.

This patient was clinically suspected of pyelonephritis.

On the spot of maximum tenderness with the probe in intercostal position, an inflamed appendix (arrow) was visualized.

CT confirmed the unusual location (arrows).

A successful laparoscopic appendectomy was done.

Two patients with unusual clinical presentation due to unusual location of the inflamed appendix (arrows) in the left upper quadrant (left panel) and at the level of the umbilicus (right panel)

This 58-year old female presented with a slightly painful mass in the groin since two weeks and a low CRP.

US revealed an incarcerated, edematous appendix (arrow) surrounded by non-compressible fat in a femoral hernia (Garengeot hernia).

Hernioplasty was done, the appendix was not resected.

CT scan, performed for other reasons 17 years later (patient now 75 years), showed the appendix (arrows), still doing fine.

This patient with severe COPD presented with a painful mass in the right groin, suspect for incarcerated hernia or a purulent lymphadenitis.

CRP was 110.

US revealed a puscollection and an inflamed appendix (arrow) within a femoral hernial sac, confirmed by CT.

In view of his comorbidity, only abscess drainage was performed, with success.

Uneventful recovery thereafter.

No interval appendectomy.

“Foie appendiculaire”

Nowadays exceedingly rare, the so-called “foie appendiculaire” was a feared complication in the pre-antibiotic era.

This patient had longstanding appendicitis with multiple abscesses, one of them containing a fecolith (arrow).

In the portal vein a septic thrombus (arrowheads) is visualized while there are many, small, ill-defined liver abscesses (*).

Early complications after appendectomy

Post-operative abscess

Post-operative abscesses can be seen, even after uncomplicated appendectomy for non-perforated appendicitis.

In wound abscess there is little role for US and CT, in contrast to their role in intra-abdominal abscesses.

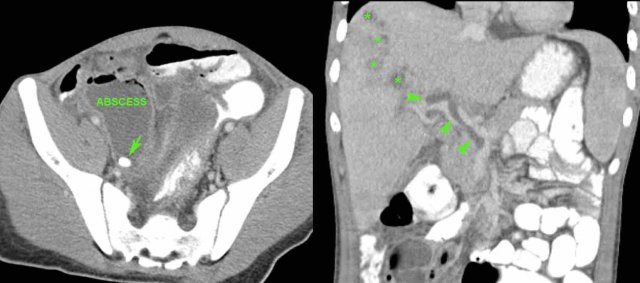

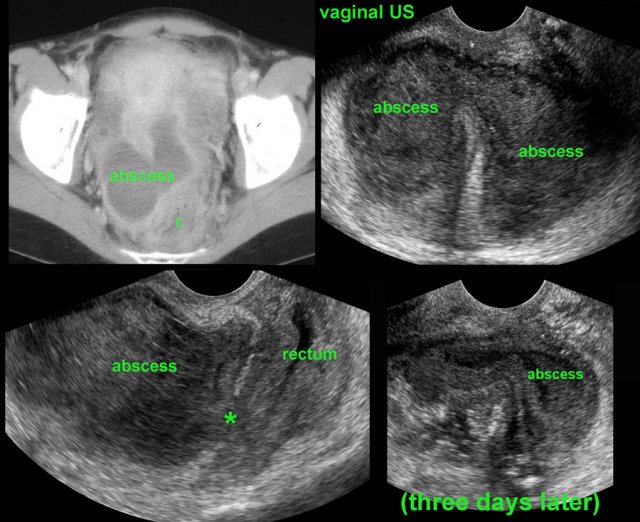

This 25 year old woman presented ten days after surgery for perforated appendicitis with fever.

She had a Douglas abscess, lying close to the rectum (r.) showing a thickened wall.

Vaginal US confirmed the abscess and secondary rectal wall thickening.

At the spot of closest contact (*) the wall layers of the rectum were locally obliterated.

Follow-up vaginal US showed complete, spontaneous transrectal evacuation.

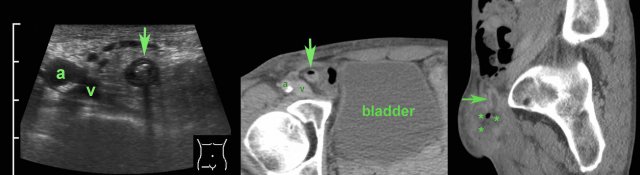

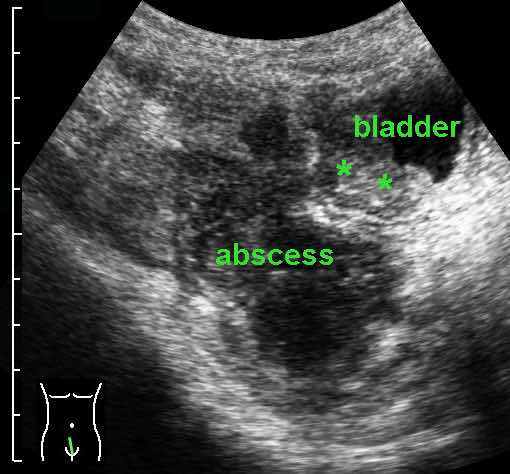

A 9-year-old, with persistent RLQ pain and painful micturition, two weeks after appendectomy for perforated appendicitis.

CRP 220.

He was not very ill.

US shows a large, irregularly defined Douglas abscess with reactive thickening of the bladder wall (**).

He had a few days of smelly stool (spontaneous evacuation of pus to the rectum) and made a full recovery without antibiotics or surgery.

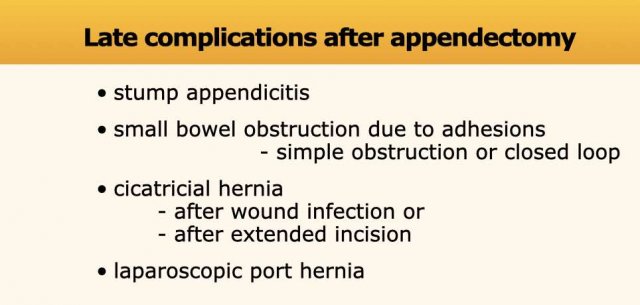

Late complications after appendectomy

Late complications after appendectomy are shown in the table.

Stump-appendicitis

This patient underwent a difficult appendectomy for longstanding appendicitis, resulting in a so-called “hockeystick-prolongation” of the McBurney incision, complicated by post-OR abscesses.

Three years later, he presented with pain in the RLQ and elevated WBC and CRP.

US revealed a 4 cm long, inflamed appendix: stump-appendicitis.

Surgery confirmed inflammation of a 4 cm appendix stump.

Apparently the appendix was not completely removed during the initial operation.

Stump-appendicitis is more often seen:

- After difficult appendectomy, often unnoticed by the surgeon

- After laparoscopic appendectomy

If small and close to the cecum, conservative management is possible just like in cecum diverticulitis.

This is a 34-year-old woman with mild clinical signs of appendicitis and a CRP of 125.

US was inconclusive.

CT showed a small stump appendicitis containing a fecolith.

At surgery the stump could only be removed by stapling-off part of the cecal pole.

In hindsight, conservative management would have been a good alternative, as the fecolith probably would have evacuated spontaneously to the cecal lumen.

Eight months after a complicated appendectomy with open wound healing, this 52-year-old woman had pain in the RLQ.

US and CT revealed a 2 cm stump appendicitis (arrows).

Note also the large cicatricial hernia, as a late result of the infected operation wound.

Small bowel obstruction due to adhesions

A man of 61 years old presents with severe crampy pain over the entire abdomen since 6 hours.

WBC 13, CRP 1.

He had an appendectomy 9 years earlier.

US of the RLQ reveals dilated small bowel loops, that are not well compressible (arrowheads) and some free fluid.

Continue with next images...

Both clinical and US images are suspect for a closed loop obstruction.

CT scan was performed immediately and confirmed a closed loop obstruction with a large bunch of dilated converging loops with edema, and two transition points (arrowheads), close to each other.

The invisible adhesion is represented by the small half loop.

Continue with the next images...

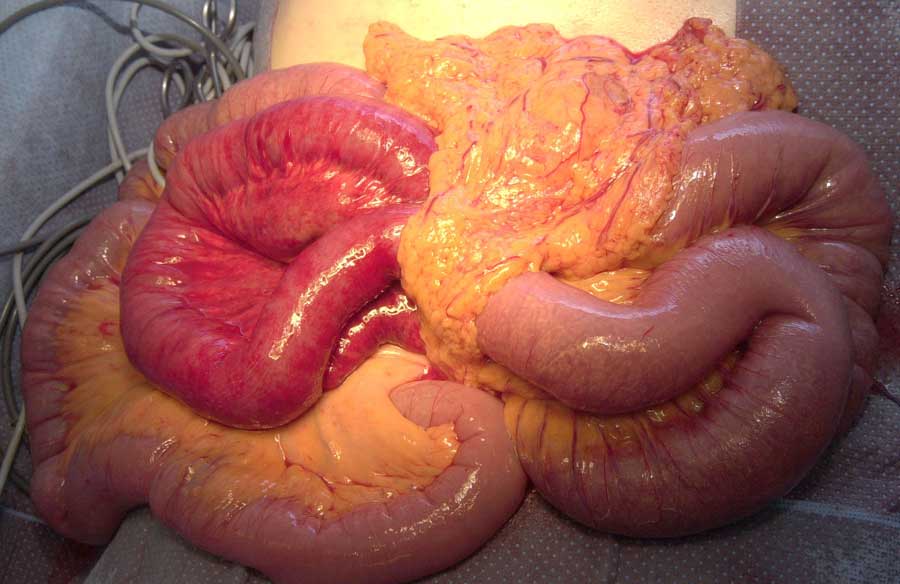

Immediate surgery confirmed a closed loop obstruction due to an adhesion in the RLQ.

After cutting the adhesion, the strangulated bowel quickly regained a normal color and peristalsis.

No resection was necessary.

Uneventful recovery.

Cicatricial hernia

Image of a 47-year-old obese woman with a very painful umbilical mass, three years after laparoscopic appendectomy.

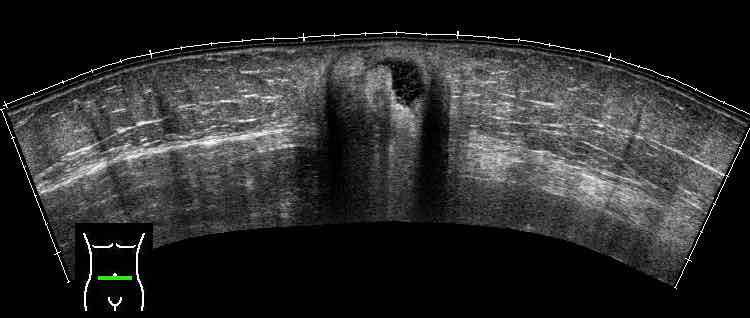

Panoramic US demonstrated an incarcerated slip of the omentum within an port site hernia.

-iffi-re-gifje-1594469586.gif/eaabfdad863abc011aeddc49d11024f8.gif)