US of the GI tract - Technique

Julien Puylaert

Medical center Haaglanden in the Hague and Academical Medical Center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

The GI tract is the most challenging part of the abdomen to examine by US.

Although technically demanding, its results have great clinical implications in early triage of bowel diseases and in the acute abdomen.

This is the first of a series on US of the GI tract.

Press ctrl+ for larger images and text on a PC or ⌘+ on a Mac.

This can be helpful for scroll-images.

Single images can be enlarged by clicking on them.

For critical comments and additional remarks: [email protected]

Examination technique

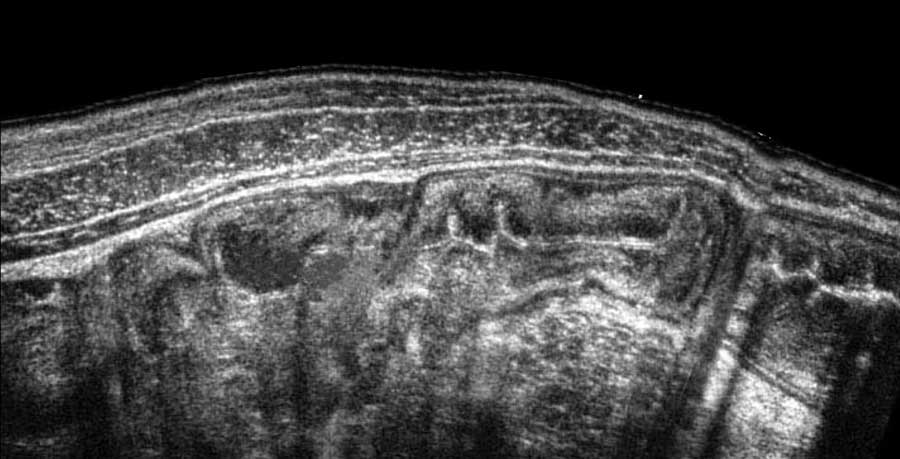

Modern ultrasound machines provide high resolution images of the GI tract, like in this patient with massive thickening of mucosa and submucosa in Clostridium colitis.

However nowadays cheap ultrasound systems consisting of a 1200 euro transducer connected to a tablet or phone will produce images of good quality (see next image).

We expect that more doctors and health workers will use ultrasound in their daily practice.

Knowledge of technique, normal anatomy and pathology of the GI tract will be important for patient management.

US machines and probes

- US machines are getting better, smaller and less expensive.

- In the future one probe connected to a tablet, covering 0-25 cm depth.

- At present a high-end US machine for GI tract still mandatory.

- Learning US is best mastered by practicing on thin patients with a high-end machine. This expertise will enable to successfully exam obese patients with a less fancy probe.

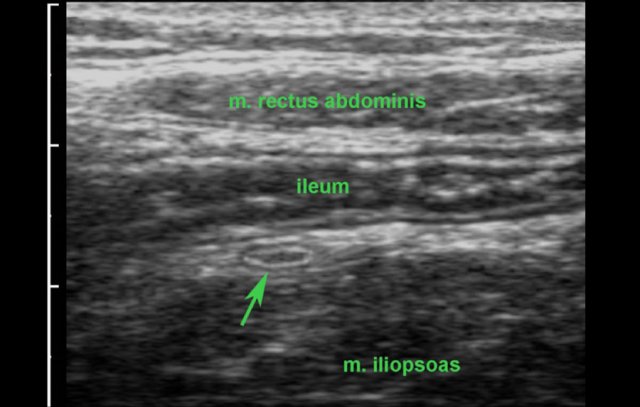

In this lean person, the normal terminal ileum and the normal, compressed appendix (arrow) are visualized on a tablet connected to a 1200 euro probe.

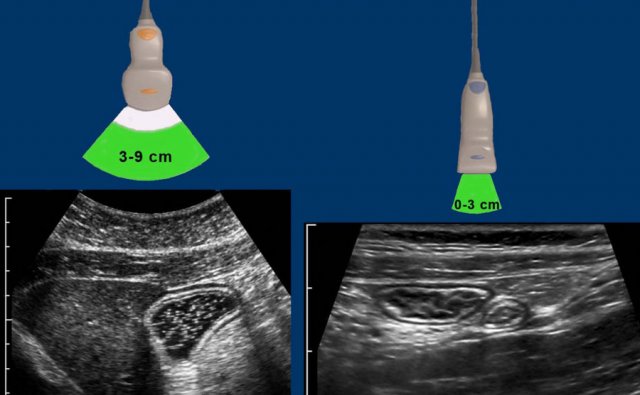

For the average abdominal US program with patients of varying habitus, still three probes is the minimum.

The cm’s indicate the range where image resolution is optimal.

Since bowel lies close to the abdominal wall, the middle and small probe are the workhorses in US of the GI tract.

Choice of the probe is based on the depth where the bowel is visualized during compression.

For example, the fluid-filled stomach in this obese patient (left), is best studied with the middle-transducer, the normal ileum and appendix in a thin patient (right), with the small transducer.

Pre-sets for specific abdominal organs can be helpful, but we use only two abdominal pre-sets per probe: normal and XL for large and obese patients.

The “over-processed” US image

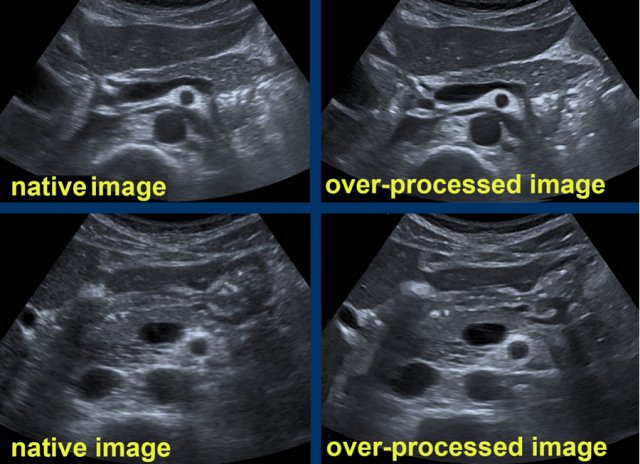

The processed US image: speckle-noise-reduction

- Advantages: sharper reflective contours, anechoic cysts and vessels, “smoothed image”

- Drawbacks: creation of unrealistic boundaries and reflections, lower image resolution

- Use with great caution, as confusing artifacts may outweigh its advantages

Compare the native US images (left) of the pancreatic region with the strongly processed US images (right).

In these over-processed images the vessels have a sharper delineation with a completely anechoic lumen.

However, also unrealistic reflections and contours are “created”.

Note the unnatural bright reflections in the area dorsal from the pancreatic tail (right upper image) and note the bizarre contour of the stomach and the falciform ligament (right lower image).

US examination of bowel

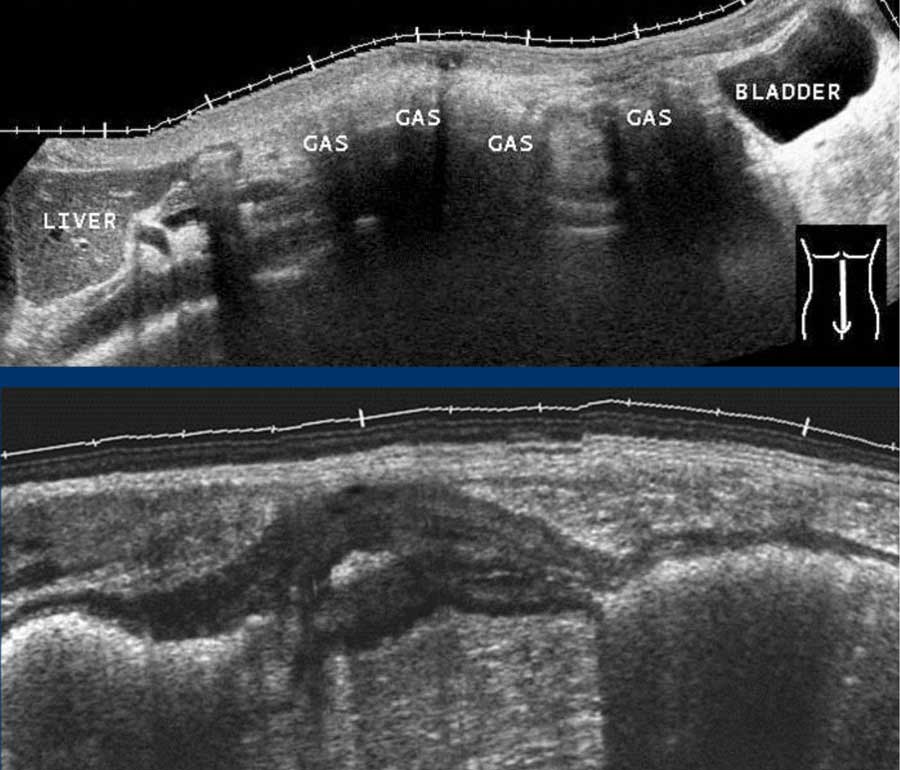

US of the GI tract has been quite unpopular in the past because of the interference of gas and other bowel contents (upper image).

The good news is that pathological bowel usually is often conspicuous, due to local wall thickening and an empty lumen, e.g. in this patient with segmental Crohn’s colitis (lower image).

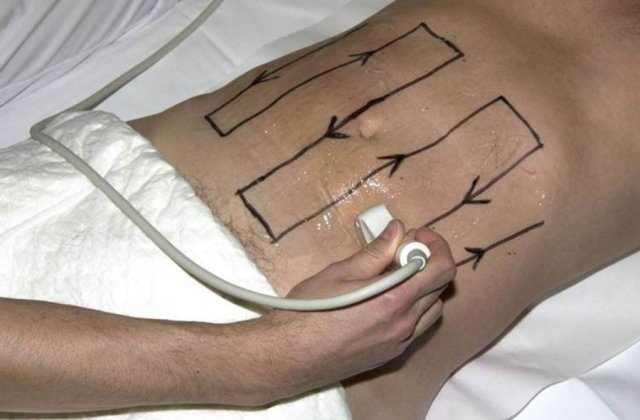

Searching and screening for bowel pathology is best done using the so-called “mowing-the-lawn” technique.

This technique requires graded compression, a high-frequency probe and not too viscous US gel.

Like in mowing the lawn, overlapping lanes are necessary, not to miss any pathology.

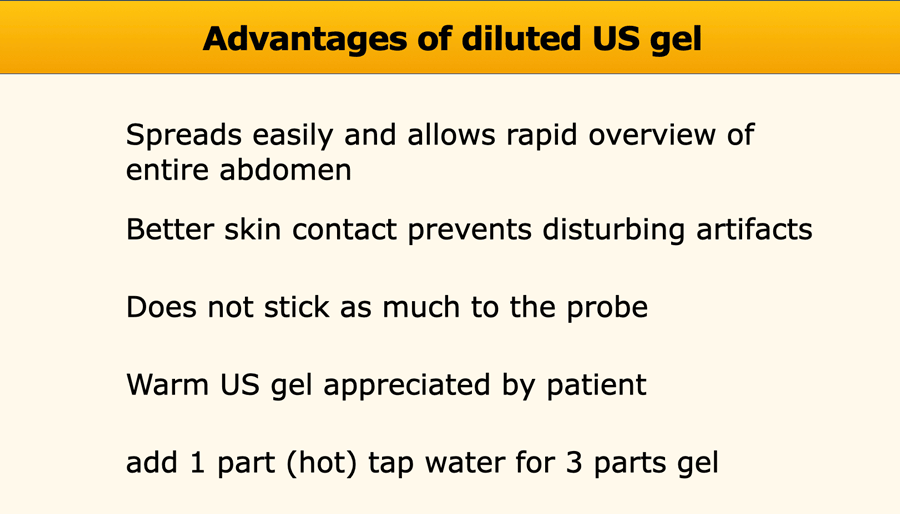

Most commercially available US gels are quite viscous.

It has several advantages to make it more fluent by adding about one third of hot tap water.

Better skin contact prevents disturbing air-artifacts (arrowheads).

It is time-efficient to put the US gel on the patient, and not on the probe.

With a normal habitus, one large dose ( ~25 cc) of diluted US gel is sufficient for the entire examination.

A small reservoir in the epigastric area may be used for “dipping”.

In general, liberal use of US gel has great advantages.

There are however two drawbacks: things may get quite messy and hygiene may be endangered.

This requires “US gel discipline” and a lot of towels or cleaning tissue.

To avoid the cable getting sticky, you can put it around your neck or place it on the patient’s chest when studying the left flank.

US gel should be removed from the probe, before putting the probe back.

Proper cleaning of the probes after each patient speaks for itself.

Ask the manufacturer what to use as cleaning fluid.

It is very important to keep the fingers of the probe-hand free of US gel: the combination of rather forceful compression with subtle rotational movements requires a dry hand.

Graded compression

Advantages compression

- closer to the bowel allows high frequency probe

- compressing and/or displacing gas-filled bowel

Compression should be graded and gentle

- not to cause pain

- to avoid pushing bowel entirely out of the US plane

Graded compression is remarkably well tolerated, even in peritonitis.

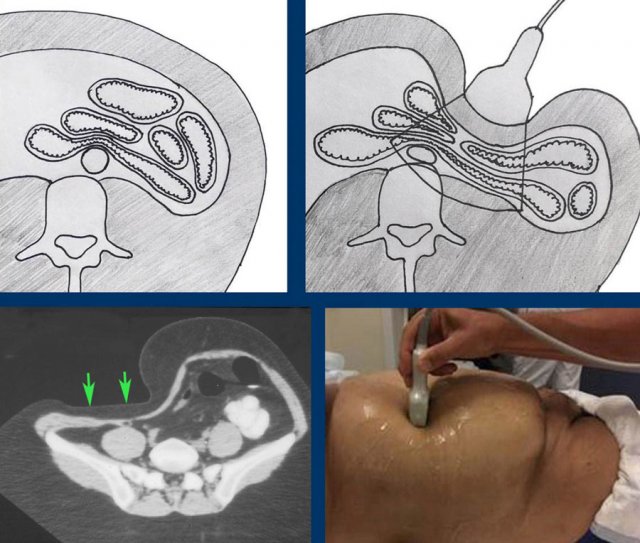

The CT scan shows how intra-abdominal anatomic relations are altered by graded compression.

During compression, the ventral wall of the bowel is compressed against the dorsal wall, eliminating the disturbing effect of gas and other bowel contents.

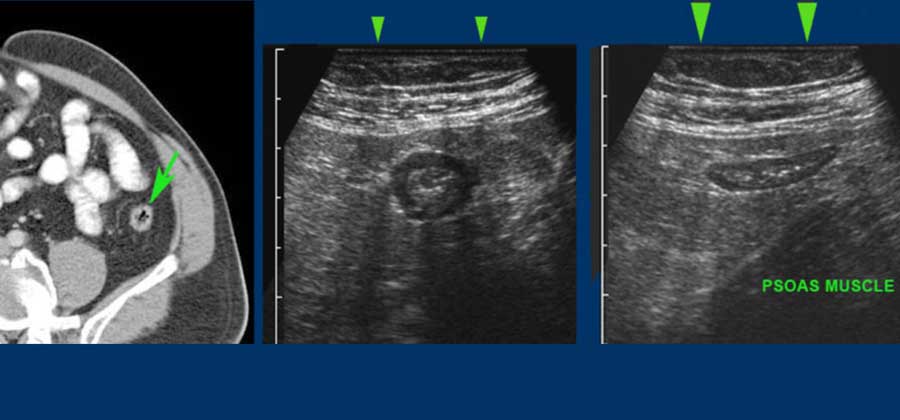

This sagittal CT scan demonstrates a retrocecal, inflamed appendix (arrowheads) with an obstructing fecolith (arrow).

By graded compression with the US probe, the air-filled cecum is pushed aside and the appendix is visualized close to the abdominal wall (note cm-scale).

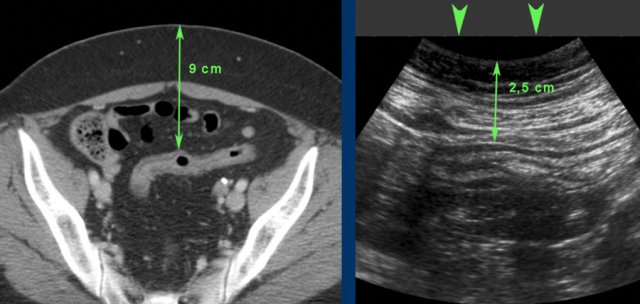

CT shows contracted colon (arrow) in obese patient.

During light compression (middle) the contracted colon can be visualized with a 12 MHz probe.

During moderate compression (right), the relaxed colon can even be seen flattened against the dorsally located psoas muscle.

CT of an obese patient with inactive ulcerative colitis. The sigmoid lies 9 cms from the skin.

During compression (arrowheads) this distance was decreased to 2.5 cms allowing the use of a high frequency probe.

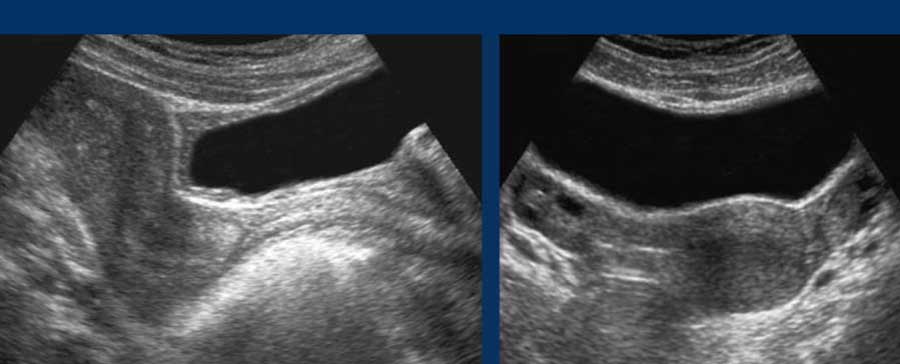

To visualize a tubular structure (e.g. the inflamed appendix) in two perpendicular planes, it is essential to bring the structure in its axial view in the middle of the US image.

This allows to keep the structure visible, while rotating the probe 90 degrees (click on image).

Gentle “rocking” of the probe during rotation helps in keeping a small tubular structure in sight.

The rather ovoid than round shape of most probe-handles is not very helpful in making easy and subtle rotational movements combined with compression.

Try to develop a grip that allows you to rotate the probe from your wrist, and not from your arm or shoulder, always trying to hold the red line axis.

Preparation of the patient

- Allow light breakfast (a cup of tea, juice, some crackers etc.)

- No ratio for absolute fasting (unpleasant, hazardous for diabetics, patients may skip vital medication)

- No full bladder (unpleasant for the patient and hampers the US examination hindering compression and displacing bowel dorsally).

- A half-full bladder is best, but it may be difficult to instruct patients

A half-full bladder allows optimal examination of the bladder and distal ureters and uterus and ovaries in women (images).

In patients with acute abdominal pain, preparation is not an issue: most of the patients have not eaten or have vomited, and are readily instructed not to eat or drink, until a surgical condition is ruled out.