Ultrasound in Acute Abdomen

Julien Puylaert

Department of Radiology, MCH Westeinde Hospital, The Hague, The Netherlands

Publicationdate

Multi-slice CT is increasingly replacing ultrasonography for the evaluation of patients with acute abdominal pain.

Ultrasound however has specific advantages.

This review will focus on:

- The advantages of US compared to CT

- US technique

- The use of US in patients with Acute abdomen

- Pittfalls in the diagnosis of Appendicitis

For critical comments and additional remarks: [email protected]

Introduction

Why perform ultrasonography when you have CT ?

Multi-slice CT is increasingly replacing ultrasonography (US) for the evaluation of patients with acute abdominal pain

CT has major advantages over US: it is extremely fast and its time burden is often less than that of a US examination (1-4).

CT is not disturbed by gas and bone, while obesity is even an advantage.

Most of all, CT is not operator-dependent and can be reviewed by others, even at a distance.

With all these advantages, it is not surprising that US is losing field in the evaluation of the acute abdomen.

US however has some advantages.

Specific advantages of US

- US does not require ionizing radiation, which can be important in younger patients and pregnant women (5).

-

The spatial resolution of a high-frequency US image is higher than that of a CT image (Figure).

This is only true if the target organ can be approached closely, which requires either a thin patient or the use of graded compression.

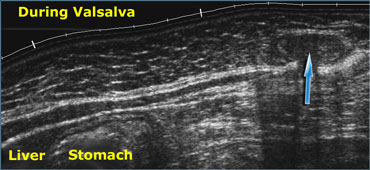

Realtime US allows to observe the effects of Valsalva manoeuvre. Intra-abdominal fat is pressed into the abdominal wall (arrow) through an epigastric hernia.

Realtime US allows to observe the effects of Valsalva manoeuvre. Intra-abdominal fat is pressed into the abdominal wall (arrow) through an epigastric hernia.

Specific advantages of US (2)

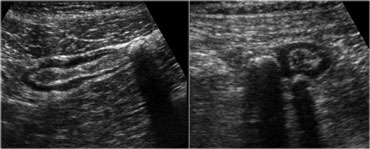

- The dynamic, real-time qualities of US are unique. US can observe fetal movements, peristalsis and also absence of peristalsis as in paralytic ileus.

US can directly visualize blood flow and pulsations, and it is also possible to appreciate the effects of respiration, Valsalva maneuver, gravity and compression.

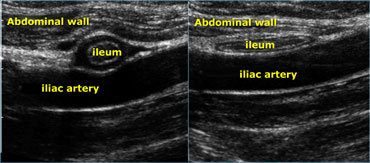

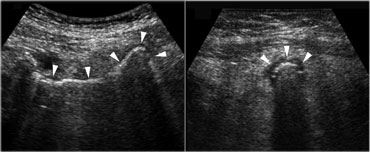

Realtime US allows to observe the effect of compression. Compare the contracted normal ileum (left) with the relaxed, flattened ileum in the same patient a few seconds later (right)

Realtime US allows to observe the effect of compression. Compare the contracted normal ileum (left) with the relaxed, flattened ileum in the same patient a few seconds later (right)

- The latter is especially useful to judge whether organs or tissues are soft or rigid.

Real time US allows one to observe the effect of compression.

On the far left a contracted normal ileum and next to it a relaxed flattened ileum a few seconds later.

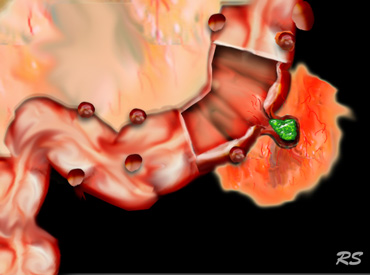

US guided puncture of intraperitoneal fluid reveals purulent nature of the fluid in a patient with perforated appendicitis.

US guided puncture of intraperitoneal fluid reveals purulent nature of the fluid in a patient with perforated appendicitis.

Specific advantages of US (3)

- The advantage of US over CT is that it allows precise correlation of the US findings with the area of maximum tenderness or with a palpable mass with.

- Another advantage of US is its mobility and flexibility: It can be done in the Emergency Ward, High Care Units and the Operating Room, and with the present generation of small, battery-assisted, hand-held units, in fact anywhere.

- Furthermore, in case of intraperitoneal fluid, US guided puncture is a safe and rapid way to determine if the fluid is blood, pus, bile, amylase, gastric contents, etc. (Figure).

-

US examination allows a natural and direct form of communication with the patient.

Information provided by the patient may lead to a specific search for a US finding, while, vice versa, certain US findings may lead to a specific question to the patient.

This interactive aspect is perhaps the greatest secret of a successful US examination. If performed in this way, US is much more than depicting abdominal organs.

As the examination proceeds, it is possible to correlate the US findings with the clinical data, the laboratory results, other imaging studies and the information provided by the patient.

Doing so, the long list of possible differential diagnoses will continuously narrow down until a definitive diagnosis is established, or at least, direction is given to subsequent imaging studies.

The point of maximum tenderness and a possible palpable mass, are correlated with the US findings and in case of free fluid, US guided puncture can be done (Figure).

Who does the US examination ?

Worldwide, there is a large variation of who performs the US examination of the acute abdomen. US is done by technicians, general radiologists, radiologists specialized in US, abdominal radiologists, and all sorts of clinicians, urologists, gynecologists and even family doctors.

The US examination performed as described above, requires a person with a thorough medical background, knowledge of all possible causative conditions (urological, gynecological, gastrointestinal, vascular, etc.), and with a large expertise in US as well as in CT, imaging guided puncture and other radiological imaging.

There is no doubt that the person who meets these conditions best is the radiologist, and preferably a radiologist with special interest in abdominal US and CT.

Additional advantages of concentrating all primary, diagnostic abdominal US examinations within the Radiology Department are obvious: It guarantees integrated imaging, constant quality, round-the-clock coverage, continuity, central archiving and accurate and early triage of patients with abdominal symptoms (6).

US Technique

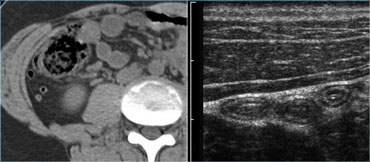

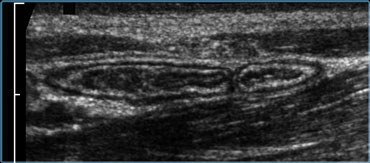

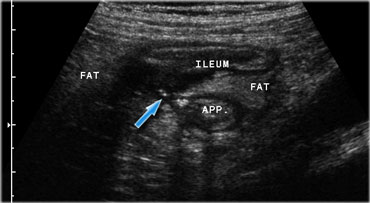

Normal ileum and appendix during compression. Thin habitus of the patient and the application of compression allow the use of a 13.5 MHz transducer with a high image quality.

Normal ileum and appendix during compression. Thin habitus of the patient and the application of compression allow the use of a 13.5 MHz transducer with a high image quality.

US examination in patients with acute abdominal pain requires a specific technique of graded compression.

In this way fat and bowel are displaced or compressed.

This eliminates the disturbing influence of bowel gas and reduces the distance from the transducer to the appendix, allowing the use of a high frequency probe with better image quality (Figure).

This technique also allows assessing the rigidity of a structure by evaluating its reaction upon compression In order to avoid pain, the compression should be applied slowly and gently, similar to the classic palpation of the abdomen.

Acutely inflamed appendix in deep pelvic position. The appendix could only be visualized with the help of a transvaginal probe.

Acutely inflamed appendix in deep pelvic position. The appendix could only be visualized with the help of a transvaginal probe.

The entire abdomen is examined to exclude disease of gallbladder, pancreas, kidney, aorta, stomach, small and large bowel, appendix, uterus and ovaries.

A moderately filled bladder allows better survey of the distal ureters, and of uterus and ovaries in women; however, a full bladder does not allow proper graded compression.

Transvaginal US may be used for gynecological conditions but also for pelvic appendicitis, diverticulitis and Douglas abscesses.

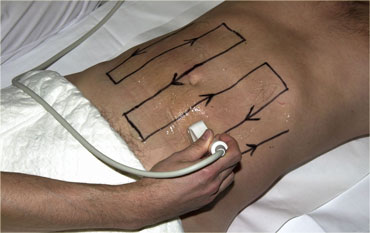

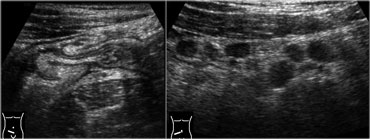

The peritoneal cavity is screened for bowel pathology with five to six vertically oriented, overlapping lanes using a broad based, high frequency probe.

We refer to this as 'mowing the lawn' (Figure).

This form of screening is facilitated by the use of thin-liquid US-gel.

Bowel pathology is usually conspicuous, because the diseased and empty bowel has a thickened and hypoechoic wall, which contrasts with the surrounding hyperechoic fatty tissue.

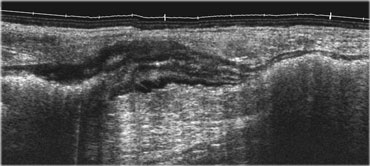

On the left a patient with segmental colitis caused by Crohn's disease.

The pathologic bowel segment is easily picked up using the 'mowing-the-lawn' technique.

Appendicitis

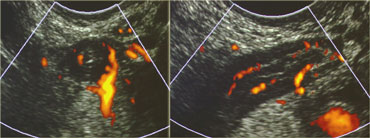

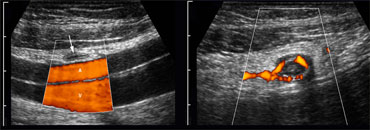

LEFT: The normal appendix is small, compressible, contains no Doppler signal, and is not surrounded by inflamed fat .RIGHT: The inflamed appendix is large, non-compressible and hypervascular, and is surrounded by hyperechoic, non-compressible tissue, representing the fatty mesoappendix

LEFT: The normal appendix is small, compressible, contains no Doppler signal, and is not surrounded by inflamed fat .RIGHT: The inflamed appendix is large, non-compressible and hypervascular, and is surrounded by hyperechoic, non-compressible tissue, representing the fatty mesoappendix

Acute appendicitis is the most common abdominal surgical emergency in the Western World.

The diagnosis may be easy but may also be very difficult.

The clinical diagnosis of appendicitis is as often wrongly made as it is initially overlooked, leading to unnecessary surgery, respectively to ill advised delay.

Using US it is possible to confirm appendicitis by visualizing the inflamed appendix (successful in 90 %) or to exclude appendicitis, either by visualization of the normal appendix (successful in 50%) or by demonstrating an alternative condition (possible in 20 %).

This means that there will always be a rather large group of patients in whom the US result is equivocal making further studies necessary.

A fortunate circumstance is that most of the patients in the latter group are obese, and therefore suitable for CT.

Normal appendix

The normal appendix presents as a small, easily compressible, concentrically layered, mobile, blind-ending, sausage-like structure.

A diameter up to 7mm is regarded as normal.

The normal appendix is mobile, may have a collapsed lumen, but also may contain air or some fecal material, and rarely a little fluid (6).

Power Doppler reveals scarce or no vascular signal and there is no hyperechoic, non-compressible inflamed fat around the appendix.

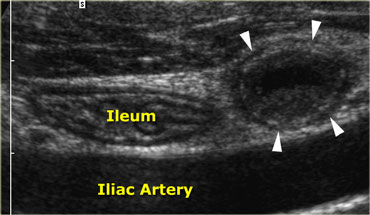

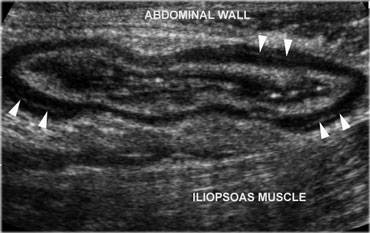

Acute appendicitis. Noncompressible, inflamed appendix (arrowheads) lies next to the normal well-compressable ileum. The lumen is dilated and the diameter is 11 by 13 mm. Note the fluid-debris level within the lumen.

Acute appendicitis. Noncompressible, inflamed appendix (arrowheads) lies next to the normal well-compressable ileum. The lumen is dilated and the diameter is 11 by 13 mm. Note the fluid-debris level within the lumen.

Appendicitis

The typical appearance of an inflamed appendix is that of a concentrically layered, non-compressible sausage-like structure demonstrated in a fixed position at the site of maximum tenderness (Figure).

The average maximum diameter is 9 mms with a variation from 7 to 17 mms. In 30% intraluminal fecoliths are found actually obstructing the lumen.

Six to 12 hours after the onset of symptoms, the inflammation progresses to the adjacent fat of the meso-appendix, which becomes larger, more hyperechoic and less compressible.

Later on, this fatty tissue will tend to increase in volume around the appendix: this represents mesentery and omentum, which have migrated towards the appendix in an attempt to wall-off the imminent perforation.

Acute appendicitis. The inflamed appendix shows local disturbance of the layerstructure indicating local transmural progression of the infection. The surrounding inflamed fat will probably effectively wall-off the imminent perforation.

Acute appendicitis. The inflamed appendix shows local disturbance of the layerstructure indicating local transmural progression of the infection. The surrounding inflamed fat will probably effectively wall-off the imminent perforation.

Slowly applied intermittent compression is the best way to identify the non-compressible inflamed fat (Figure).

An irregular, asymmetrical contour and loss of the layer structure of the appendix indicate perforation or imminent perforation.

Vascularization of the appendiceal wall is either markedly increased or absent due to high intraluminal pressure with concomitant ischemic necrosis, however there is always increased vascularization in the directly surrounding fatty tissue .

The presence of a generalized, adynamic ileus is suspect for perforated appendicitis, even if the inflamed appendix cannot be visualized.

Inflamed appendix in unusual high position in a patient with clinical signs of cholecystitis. Due to its abnormal position far from McBurney's point (McB), the appendix was drawn on the skin with a waterproof pencil. This influenced site, size and orientation of the incision and facilitated the appendectomy.

Inflamed appendix in unusual high position in a patient with clinical signs of cholecystitis. Due to its abnormal position far from McBurney's point (McB), the appendix was drawn on the skin with a waterproof pencil. This influenced site, size and orientation of the incision and facilitated the appendectomy.

A small quantity of free intraperitoneal fluid is aspecific.

It may be present in both non-perforated and perforated appendicitis as well as in many other conditions, both surgical and non-surgical.

A large quantity of fluid in the presence of an inflamed appendix may represent pus from perforated appendicitis and then is usually accompanied by paralytic ileus.

Larger quantities of free fluid are also found in perforated peptic ulcer (note air and food particles) and gynecological conditions (puncture usually reveals blood).

In most patients with appendicitis inflamed mesenteric lymph nodes can be demonstrated higher up in the mesenterial root.

In case of an abnormal position of the inflamed appendix far from where the usual gridiron-incision is made, it is useful to indicate the location of the appendix on the skin of the patient with a waterproof marker.

This may influence site, size and orientation of the incision.

Spontaneous resolving appendicitis. LEFT: inflamed appendix with a dilated lumen and a diameter of 11mm. Patient experienced rapidly subsiding symptoms and did not undergo operation.RIGHT: Two days later the patient was symptom free. The appendix has decreased in size.

Spontaneous resolving appendicitis. LEFT: inflamed appendix with a dilated lumen and a diameter of 11mm. Patient experienced rapidly subsiding symptoms and did not undergo operation.RIGHT: Two days later the patient was symptom free. The appendix has decreased in size.

Spontaneous resolving appendicitis

If the clinical symptoms rapidly subside despite the presence of an unequivocally inflamed appendix on US, one should consider the diagnosis of spontaneously resolving appendicitis.

These patients initially have the typical clinical signs of appendicitis, but within 12-48 hours after the onset of pain the clinical symptoms relatively abruptly subside, probably due to relief of obstruction.

On US follow up, the appendix usually decreases in size in the course of days.

If the patient recalls similar previous attacks, immediate appendectomy is advisable, even if the patient is again completely free of symptoms at that time.

Histology in such cases will nevertheless- confirm acute inflammation.

In case conservative management is opted for, keep in mind that there is a recurrence rate of approximately 40 % (8).

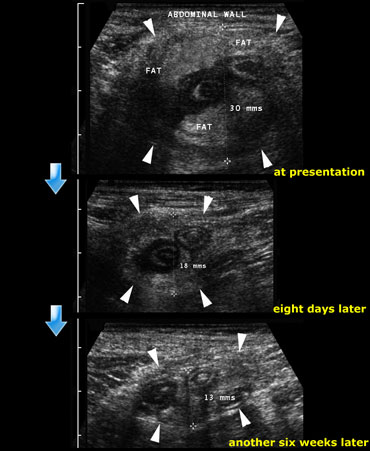

Resolution of an appendiceal phlegmon: At presentation, eight days later and finally another six weeks later.

Resolution of an appendiceal phlegmon: At presentation, eight days later and finally another six weeks later.

Appendiceal mass

Patients, who are admitted with considerable delay may present with a palpable mass and relatively mild peritonitis.

In these patients, who usually have a high ESR, US shows a large mass of non-compressible fat around the appendix, interspersed with echolucent streaks .

These patients are diagnosed as 'appendiceal phlegmon' and are usually managed conservatively because the surgeon knows that appendectomy in such cases is technically difficult or even impossible (9).

On the left a 35-year old man with a 10-day history of abdominal pain in the right lower quadrant.

At examination a palpable mass was found.

There was no evidence of peritonitis.

On the top image the US reveales a large noncompressable inflammatory mass consisting of the inflamed appendix, mesentery and omentum.

Patient was treated conservatively.

Follow up examination at 8 days and another 6 weeks later showed still some residual abnormalities.

The patient was completely symptom free.

There were no recurrent symptoms and the patient did not undergo operation.

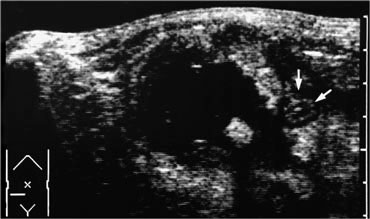

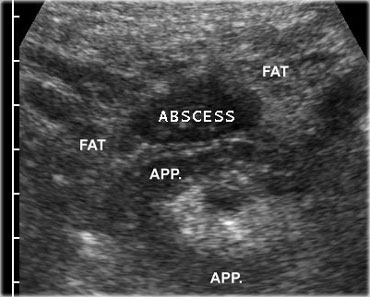

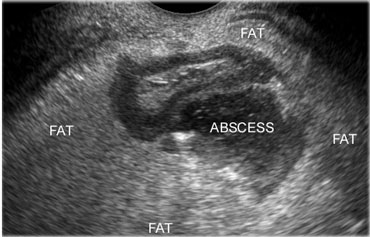

If next to the inflamed appendix, a fluidcollection is found, this is suggestive for an appendiceal abscess.

The collection often contains air and is surrounded by inflamed non-compressible hyperechoic tissue representing omentum and mesentery as well as secondarily thickened neighboring bowel loops, attempting to seal-off the abscess from the peritoneal cavity.

If an appendiceal abscess is demonstrated and there is no frank peritonitis, percutaneous drainage is the treatment of choice.

In stable patients who have no fever and only mild pain, it can be even wise to await spontaneous drainage of the abscess to neighboring bowel.

On the left an abscess cavity that contains a fecolith.

Note the inflamed appendix (arrows) lying next to the abscess.

Better off with immediate surgery

Finally, there are some patients with an appendiceal abscess who are better off with immediate surgery: this goes in general for children and for those patients with severe peritonitis, which indicates that the walling-off process is failing.

Immediate surgery is also indicated for patients who have a small abscess with a history of only a few days of symptoms, in whom appendectomy with evacuation of the abscess is usually technically easy (Figure).

On the left a patient with a 4-day history of right lower quadrant pain.

There was peritonitis at physical examination.

The sedimentation rate was 48mm/hour. Palpation was unreliable.

Subsequent appendectomy with evacuation of the abscess was performed without technical difficulties.

Prior to percutaneous drainage, CT is necessary to delineate the extent of the abscess and to determine the safest access route.

If expertise is available in US guided puncture, the combination US plus fluoroscopy has several advantages over CT guided drainage.

It is rapid, allows continuous control, any angulation, and can be performed as a bed-side procedure.

Pitfalls in the US diagnosis of appendicitis

A false positive diagnosis can be made if the normal appendix is mistaken for an inflamed one.

Not infrequently the normal appendix is larger than 7 mms, especially in children due to lymphoid hyperplasia and in adults due to fecal impaction.

Appendiceal compressibility, the absence of a Doppler signal and the absence of inflamed fat are the most important features in deciding if it is normal or inflamed.

Mistaking a normal appendix for an inflamed one may also occur if there is secondary thickening of the appendix associated with cecal carcinoma.

In the latter case, the appendiceal lumen is obstructed giving rise to sterile accumulation of mucus in the lumen.

The patient often has remarkably mild symptoms and is managed conservatively under the erroneous diagnosis of an appendiceal phlegmon.

If the underlying tumour is small and is not recognized, this may lead to considerable delay in surgical treatment.

The combination of a relatively large appendix with paradoxically mild and atypical symptoms should raise suspicion of underlying malignancy.

Other conditions with secondary thickening of the appendix are perforated peptic ulcer, Crohn's disease and sigmoid diverticulitis.

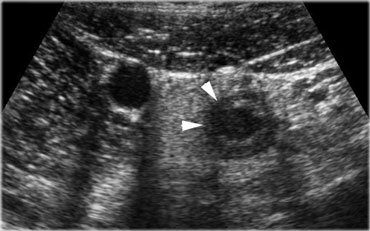

Pitfall. The inflamed appendix, demonstrated in the longitudinal (left) and axial (right) plane, has a gas-filled lumen (arrowheads), making it difficult to identify.The sausage shape and the inflamed fat are the clue to the diagnosis.

Pitfall. The inflamed appendix, demonstrated in the longitudinal (left) and axial (right) plane, has a gas-filled lumen (arrowheads), making it difficult to identify.The sausage shape and the inflamed fat are the clue to the diagnosis.

Pitfalls in the US diagnosis of appendicitis (2)

A false negative ultrasound examination is mostly the result of overlooking the inflamed appendix.

In experienced hands the inflamed appendix can be visualized in 90% of patients with acute appendicitis.

Generalized peritonitis hampers graded compression which may account for a lower score in patients with free appendiceal perforation.

Also air-filled dilated bowel loops from adynamic ileus may hide the appendix from view.

Air in the lumen can make it difficult to identify the inflamed appendix.

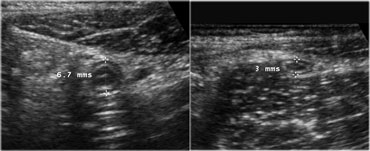

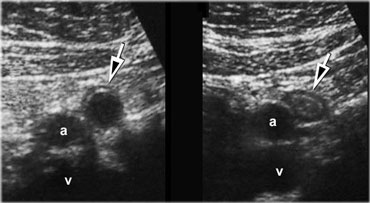

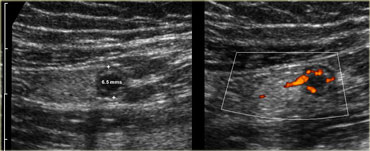

Pitfall. Acute appendicitis, but appendix has a diameter of only 6.5mm. However there is inflamed fat and an increased Doppler signal indicating that it is acutely inflamed.

Pitfall. Acute appendicitis, but appendix has a diameter of only 6.5mm. However there is inflamed fat and an increased Doppler signal indicating that it is acutely inflamed.

Pitfalls in the US diagnosis of appendicitis (3)

Another pitfall is demonstration of the normal proximal part of the appendix while the distal inflamed tip is overlooked, because it is obscured by bowelgas.

Rarely, the inflamed appendix has a maximal diameter of less than 7 mms.

In those cases rigidity, hypervascularity and the presence of inflamed fat must give the clue.

On thr left a patient with acute pain in the right lower quadrant.

The appendix has a diameter of only 6.5mm.

However there is inflamed fat and an increased Doppler signal indicating that it is acutely inflamed.

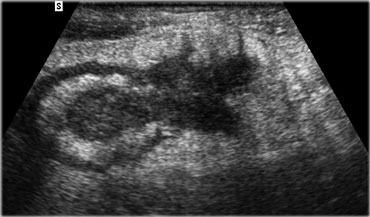

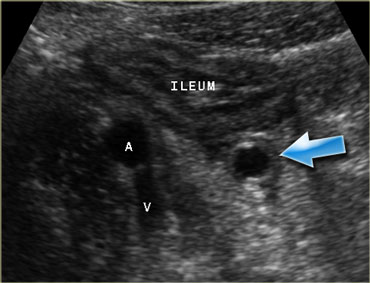

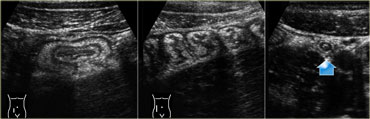

Pitfall. Secondary thickening of the ileum by appendicitis. If the prominent ileum is appreciated, but the inflamed appendix (arrow) is overlooked, an erroneus diagnosis of Crohn's disease or infectious ileocolitis can be made.

Pitfall. Secondary thickening of the ileum by appendicitis. If the prominent ileum is appreciated, but the inflamed appendix (arrow) is overlooked, an erroneus diagnosis of Crohn's disease or infectious ileocolitis can be made.

Pitfalls in the US diagnosis of appendicitis (4)

Another pitfall is advanced appendicitis where there is secondary wall thickening of the ileum.

Often the ileal thickening is more prominent and conspicuous on US than the underlying inflamed appendix (Figure).

If only the ileum is appreciated and the appendix is overlooked, an erroneous diagnosis of infectious

ileocecitis or Crohn's disease can be made, leading to ill-advised surgical delay.

Similarly, if in an adult patient enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes are the sole US finding, one should be cautious to diagnose mesenteric lymphadenitis because these nodes could be secondarily enlarged due to acute

appendicitis, while the inflamed appendix is overlooked.

If in a patient with appendicitis only the fecolith in the appendiceal base is visualized and the rest of the appendix is overlooked, this may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of cecal diverticulitis.

Pitfalls in the US diagnosis of appendicitis (5)

Also, if in a woman a relatively large rightsided ovarian cyst is found, this is not necessarily the cause of her symptoms and appendicitis should still be searched for.

Finally, if in advanced appendicitis only the hyperechoic non-compressible inflamed fat of omentum and mesentery is visualized, and the inflamed appendix is overlooked, this may lead to an erroneous diagnosis of omental infarction or epiploic appendagitis (10,11).

In patients with equivocal US findings, CT scan is indicated.

A fortunate circumstance is that these are often obese patients.

Ileocecal Crohns disease

Patients with ileocecal Crohn's disease often have protracted and atypical symptoms causing marked diagnostic delay.

On the other hand, Crohn's disease may also present with acute, appendicitis-like symptoms and lead to an ill-advized operation. In both scenarios US may play an important role in establishing the initial diagnosis (12,13).

The sensitivity of US for detecting ileocecal Crohn's disease of over 95%.

On the left a patient with Crohn's ileitis.

US reveals marked wall thickening of the terminal ileum with focal disruption of the wall and a small abscess, walled of by hypoechoic, inflamed fat.

Crohn's ileitis with fistula (arrow) to the adjacent appendix. Note the focal loss of layer structure of the ileal wall and large masses of surrounding inflamed fat (fat).

Crohn's ileitis with fistula (arrow) to the adjacent appendix. Note the focal loss of layer structure of the ileal wall and large masses of surrounding inflamed fat (fat).

Sonographically, there is marked mural thickening of the ileum, which shows decreased or no peristalsis and is not compressible.

Classically, all layers are involved and layerstructure is often locally disturbed , the earliest sign being echolucent changes in the submucosa.

There is inflammation of the fatty mesentery and omentum, recognizable as hyperechoic, non-compressible tissue adjacent to the ileum.

In the echolucent wall bright eccentric foci may indicate deep ulceration.

Echolucent streaks within the hyperechoic tissue indicate liponecrotic tracts, which may herald fistulaformation (Figure).

Cecum and appendix may also show mural thickening.

Mesenteric lymph nodes are often markedly enlarged, but hypovascular.

In longstanding Crohn's disease, 'creeping fat' is found which is recognized as a large, moderately well-compressible fatty mass encompassing most of the circumference of the ileum and iso-echoic to normal fat.

Eventually, there are often US signs of prestenotic dilatation, abscess formation, or fistulaformation.

Infectious ileocolitis and Infectious ileocecitis

Infectious ileocolitis is a bacterial infection of terminal ileum and colon which is characterized by diarrhea and abdominal pain.

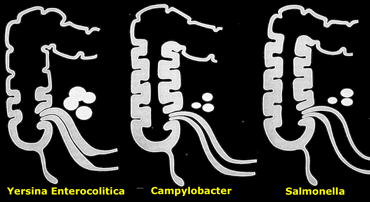

The most frequently cultured bacteria are Campylobacter and Salmonella, and Yersinia.

The infection is generally limited to the mucosa, is self-limiting and rarely poses diagnostic problems.

There is an interesting variant of infectious ileocolitis in which the infection is mainly limited to the ileocecal area and is therefore has been coined infectious ileocecitis (14).

It is usually caused by the same bacteria and the importance of this variant is that its clinial symptoms are dominated by acute right lower abdominal pain, while diarrhea is absent or only mild.

These symptoms masquerade as the clinical signs of appendicitis and explain why infectious ileocecitis often leads to an unnecessary laparotomy.

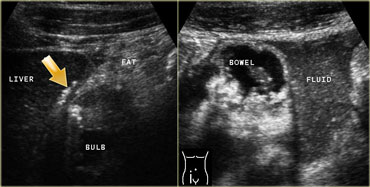

Infectious ileocecitis in a patient with clinical symptoms of appendicitis. There is marked mucosal and submucosal wall thickening of ileum and cecum.

Infectious ileocecitis in a patient with clinical symptoms of appendicitis. There is marked mucosal and submucosal wall thickening of ileum and cecum.

The symptoms of Yersinia are often more protracted and then both the clinical symptoms and the US features may mimick those of Crohn's disease.

The absence of a transmural component, the self-limiting course and of course positive stool cultures or serology will yield the correct diagnosis.

The frequency of infectious ileocecitis is fairly high and has a ratio of 1 to 8 compared to appendicitis (14).

On the left a 26-year old woman with clinical symptoms of appendicitis.

US shows prominent ileocecal valve and to marked mucosal and submucosal wallthickening of ileum and cecum.

Enlarged lymph nodes were found in the radix of the mesentery.

The appendix was normal.

Appendectomy was cancelled.

The next day the patient developed diarrhea and stool cultures eventually revealed Campylobacter jejuni.

Infectious ileocecitis. US reveals mucosal and submucosal wall thickening. The ascending colon is contracted with prominent haustration. The appendix is normal (arrow).

Infectious ileocecitis. US reveals mucosal and submucosal wall thickening. The ascending colon is contracted with prominent haustration. The appendix is normal (arrow).

In infectious ileocecitis US shows fairly characteristic features.

There is diffuse thickening of mucosa and submucosa of the terminal ileum and the cecum.

The appendix has to be sonographically normal (Figure).

In contrast to ileocecal Crohn's disease, in infectious ileocecitis, the wall layers are always intact and the muscularis and serosa, are never affected.

Also omentum and mesentery are never involved and there are never signs of bowel obstruction, abscess- or fistula-formation.

The various micro-organisms have a slightly different pattern of affecting the ileocecal area (Figure).

On the left a schematic representation of relative involvement of ileum, cecum and mesenteric nodes in infectious ileocolitis caused by Yersinia, Campylobacter, and .

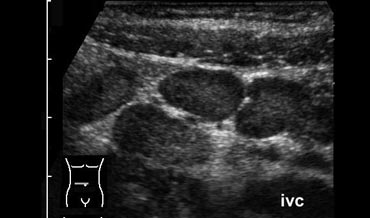

Mesenteric Lymphadenitis

This is an ill-defined entity, probably of viral origin, in which the mesenteric lymph nodes become inflamed and enlarged.

It is a typical disease of childhood and is only rarely seen in young adults. It mimicks the clinical signs of appendicitis and may therefore lead to an unnecessary appen?dectomy.

The US findings are solely enlarged, hypervascular mesenteric lymph nodes.

However if these are the only US findings in a symptomatic young adult, it is well possible that these nodes are in fact secondarily enlarged due to acute appendicitis and the inflamed appendix is overlooked.

Cecal carcinoma

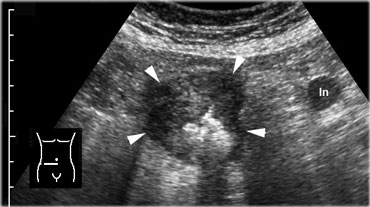

Cecal carcinoma. US reveals asymmetric, hypoechoic, circumferential wall thickening of the cecum (arrowheads) with narrowing of the lumen. There is one pathologically enlarged lymph node.

Cecal carcinoma. US reveals asymmetric, hypoechoic, circumferential wall thickening of the cecum (arrowheads) with narrowing of the lumen. There is one pathologically enlarged lymph node.

Patients with cecal carcinoma can present with acute or subacute abdominal symptoms, in several ways.

The tumour may cause acute small bowel obstruction, the appendix may be involved, the tumour may perforate and the tumour itself may cause direct pain.

The often bulky nature of the tumour and the close proximity of the right colon to the abdominal wall makes cecal carcinoma in most cases fairly conspicuous on US.

The majority presents as a hypoechoic, solid, well-vascularized irregular and asymmetrical thickening of the cecal wall (Figure).

In the proximity enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes can be found, and in most cases there is also some inflamed fat around the tumour.

In a minority of cases the tumour is of the scirrhous type, which is less easy to detect.

The finding of livermetastases of course strongly supports the diagnosis of malignancy.

Ingrowth of the tumour in the appendiceal base only rarely causes a full-blown appendicitis, but rather will lead to mucinous dilatation of the appendiceal lumen.

On US the enlarged appendix is often more conspicuous than the underlying tumour and, since there is often a palpable mass and protracted symptoms, these patients are often misdiagnosed as to have an appendiceal phlegmon, leading to significant surgical delay.

A clue to the correct diagnosis is the discrepancy between the relatively mild and protracted symptoms of intermittent, nagging pain and the impressive size of the appendix and the surrounding tissue.

Another helpful sign are markedly enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes (short axial diameter > 12 mms).

If CT is not helpful and both clinical symptoms and US abnormalities do not resolve within weeks, colonoscopy is indicated.

Sigmoid diverticulitis

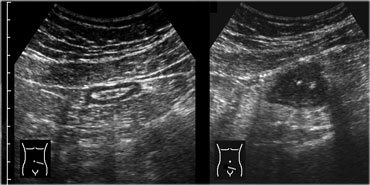

Normal, empty sigmoid. Axial view during relaxation and compression with the transducer shows the colonic anatomy the best. Note the three teniae coli, visible as a focal thickening of the muscularis layer. Note the separation of each tenia from the circular muscular layer by a thin, echogenic layer of connective tissue (arrowheads).

Normal, empty sigmoid. Axial view during relaxation and compression with the transducer shows the colonic anatomy the best. Note the three teniae coli, visible as a focal thickening of the muscularis layer. Note the separation of each tenia from the circular muscular layer by a thin, echogenic layer of connective tissue (arrowheads).

The diagnosis of sigmoid diverticulitis is often made on clinical grounds.

In the classical case the patient presents with localized pain and guarding in the left lower abdomen, fever, leukocytosis and, later on, elevation of the sedimentation rate. However, the diagnosis is not always clear.

On one hand the clinical signs may be so atypical that initially another diagnosis is considered, as urinary tract infection, renal colic, perforated peptic ulcer, adnexitis or, -in case of diverticulitis in a rightsided loop of sigmoid- appendicitis.

On the other hand, the clinician may think of sigmoid diverticulitis while in fact another condition is present, as sigmoid carcinoma, epiploic appendagitis, a gynecological or urological condition or even a ruptured aortic aneurysm.

In all of these cases, US may play a role by making the correct diagnosis at an early point in time.

On US, the normal descending colon and upper part of the sigmoid can reliably be identified in virtually all patients due to its consistent location laterally in the left paracolic gutter.

The US appearance of the normal sigmoid is variable.

The lumen can be empty or filled with feces, and the sigmoid can be contracted or relaxed (Figure).

Sigmoid diverticulosis in two asymptomatic patients. The fecalith-filled diverticula are recognized as strongly reflective, round structures casting an acoustic shadow and localized at the outer contour of the empty sigmoid. The thin wall of the diverticulum, consisting of mucosa only, is not separately visible.

Sigmoid diverticulosis in two asymptomatic patients. The fecalith-filled diverticula are recognized as strongly reflective, round structures casting an acoustic shadow and localized at the outer contour of the empty sigmoid. The thin wall of the diverticulum, consisting of mucosa only, is not separately visible.

A third factor influencing the aspect is compression by the transducer, which flattens the colon.

The muscularis in diverticulosis is often markedly thickened and fecolith-containing diverticula can easily be recognized, as large (4-12 mms), strongly reflective, round-ovoid structures casting an acoustic shadow and localized on the outside of the contour of the contracted colon.

If the sigmoid is filled with feces, the diverticula are hardly recognizable.

On the left sigmoid diverticulosis in two asymptomatic patients.

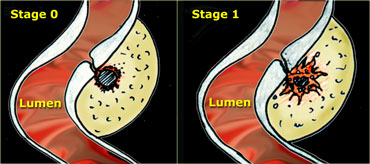

LEFT: The neck of the diverticulum becomes obstructed. Surrounding inflamed fat represents mesentery and omentum attempting to wall-off the imminent perforation. RIGHT: Development of a small paracolic abscess, successfully walled-off by mesentery and omentum.

LEFT: The neck of the diverticulum becomes obstructed. Surrounding inflamed fat represents mesentery and omentum attempting to wall-off the imminent perforation. RIGHT: Development of a small paracolic abscess, successfully walled-off by mesentery and omentum.

The US appearance of diverticulitis depends on the stage of the disease.

In the earliest stage there is usually local wall thickening of the colon, at first without but later with local blurring of the layer structure.

Around the fecolith there is hyperechoic, non-compressible tissue, which represents the inflamed mesentery and omentum trying to seal off the imminent perforation.

This inflamed fat, which is best identified during gentle, intermittent compression with the transducer, is obligatory for the diagnosis of diverticulitis (15).

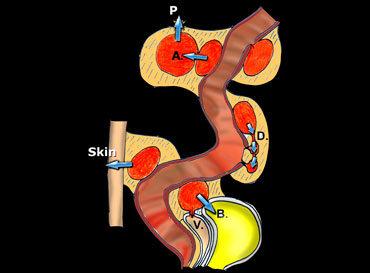

On the left a schematic presentation of the benign, natural course of sigmoid diverticulitis as it is observed in 80 % of patients.

In stage 0 the neck of the diverticulum becomes obstructed, followed by high intra-diverticular pressure and an impaired defense system against the bacteria lodging within the fecolith.

Surrounding inflamed fat represents mesentery and omentum attempting to wall-off the imminent perforation.

In stage 1 there is development of a small paracolic abscess, successfully walled-off by mesentery and omentum.

The fecolith usually disintegrates and the sigmoid wall is locally weakened.

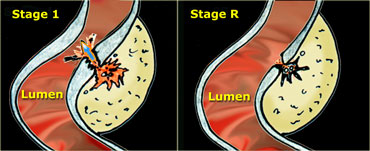

LEFT: Evacuation of pus and residual fecal material through the weakened sigmoid wall into the colonic lumen. RIGHT: Residual abnormalities remain fairly long after resolution of the symptoms.

LEFT: Evacuation of pus and residual fecal material through the weakened sigmoid wall into the colonic lumen. RIGHT: Residual abnormalities remain fairly long after resolution of the symptoms.

In over 80 % of patients, after one or two days, the pus and the fecolith evacuate towards the colonic lumen via local weakening of the colonic wall at the level of the original diverticular neck. (Figure) .

Correspondingly, the patient's symptoms resolve.

Note that the residual inflammatory changes (stage R) may remain present for a long time after the evacuation, so the patient can be completely symptomfree when there are still considerable US visible abnormalities present.

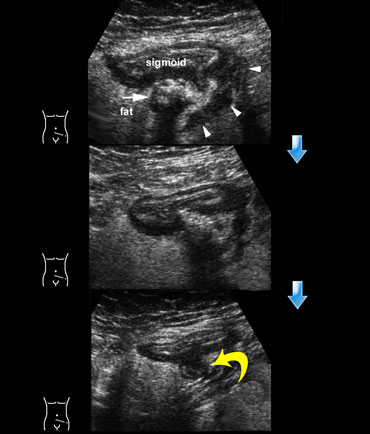

On the left the natural, benign course of sigmoid diverticulitis.

TOP: US reveals mural thickening of the sigmoid at the level of an inflamed diverticulum (arrow) containing a fecolith (stage 0).

Note the surrounding hyperechoic, non-compressible tissue representing the omentum and mesentery effectively walling-off the imminent perforation.

Within the fat, echolucent linear streaks (arrowheads) are visible.

MIDDLE: One day later the patient feels slightly better.

The fecolith cannot be recognized as such and the contents of the diverticulum are bulging towards the sigmoid lumen, sign of impending evacuation.

BOTTOM: Another two days later, the patient was almost symptomfree.

Pus and fecal material have completely evacuated to the sigmoid lumen, leaving an empty diverticulum (curved arrow).

In about 20 % of patients, diverticulitis takes a complicated course.

Free perforation without any sealing-off by mesentery or omentum, is relatively rare.

Spill of fecal material and/or pus to the peritoneal cavity quickly leads to severe peritonitis rendering laparotomy inevitable.

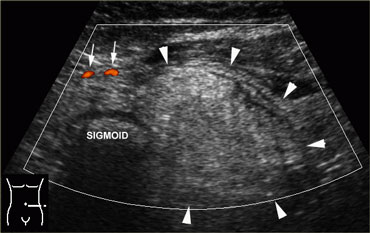

Even in case of a larger diverticular abscess (> 2.5 cms) spontaneous evacuation to the colonic lumen remains the rule (Figure).

On the left a paracolic abscess due to diverticulitis, effectively walled-off by large masses of inflamed fat, representing mesentery and omentum.

The abscess eventually evacuated completely, and the patient recovered without surgery.

Schematic presentation of the natural evolution of sigmoid diverticulitis, once a paracolic abscess has developed.

Schematic presentation of the natural evolution of sigmoid diverticulitis, once a paracolic abscess has developed.

In some patients however the abscess may evacuate in a less favourable direction (Figure).

In the first place, it may find its way to neighbouring diverticula, thus giving rise to more longitudinally oriented abscesses undermining the colonic wall.

These abscesses tend to heal badly and often lead to recurrent inflammation with stenosis eventually requiring elective surgery.

In rare cases the abscess breaks through to the peritoneal cavity which may lead to diffuse peritonitis or to secondary abscessformation.

If a diverticular abscess evacuates into bladder or vagina, a fistula may result.

On the left a schematic presentation of the natural evolution of sigmoid diverticulitis, once a paracolic abscess has developed.

The most frequent and most favourable pathway is evacuation to the sigmoid lumen.

Less favourable is breakthrough to neighboring diverticula (D), giving rise to persistent, longitudinal, cuff-like abscesses.

Even worse is the formation of secondary abscesses (A), and eventual perforation to the peritoneal cavity (P).

Finally, evacuation to bladder (B), vagina (V) and through the skin will lead to fistulaformation.

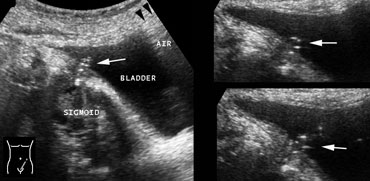

On the left a colovesical fistula from sigmoid diverticulitis.

LEFT: From the lumen of the sigmoid an air-track (arrow) can be followed all the way to the bladder.

RIGHT: In the dome of the bladder gas (arrowheads) is seen.

From the orificium of the fistula, from time to time the passage of air-bubbles (arrows) could be witnessed.

Differential diagnosis of diverticulitis

Finally, US has an important role in the diagnosis of alternative conditions: ureterolithiasis, sigmoid carcinoma, ruptured aortic aneurysm, perforated peptic ulcer, appendicitis, epiploic appendagitis.

On the left a sigmoid carcinoma in 39-year old patient with clinical signs of diverticulitis.

LEFT: Transverse image of the sigmoid 5 cms cranial to the tumour: the colon is thin-walled and well-compressible.

RIGHT: Axial US image of the tumour shows asymmetrical, moderately echolucent, wallthickening of the sigmoid.

There is also non-compressible fat around the tumour, representing a desmoplastic reaction.

On the left a 48-year old man with clinical signs of diverticulitis. br> US reveals an ovoid, non-compressible, avascular fatty mass (arrowheads) while the adjacent sigmoid has a normal aspect. br> The neighboring fat shows hyperemia (arrows). br> During respiration the mass was seen to be adherent to the parietal peritoneum. br> The patient's symptoms disappeared within a week without treatment.

These findings are typical for epiploic appendagitis.br> The mass represents the infarcted epiploic appendagebr> The patient's symptoms disappeared within a week without treatment.br>

Although in lean patients and in women using the transvaginal probe, differentiation of diverticulitis from colonic carcinoma is often well-possible, it is good practice that in every patient with diverticulitis, colonoscopy is performed when the inflammatory changes have subsided.

Percutaneous drainage of a large diverticular abscess is indicated in case of persistent spiking fever, however it is only rarely needed.

The presence of a persistent, large paracolic abscess should always raise the suspicion of underlying malignancy.

Right sided colonic diverticulitis

Rightsided colonic diverticulitis in many respects differs from sigmoid diverticulitis.

Diverticula of the right colon are usually congenital, solitary, true diverticula containing all bowel layers.

The fecoliths within these diverticula are larger, the diverticular neck is wider and there is no hypertrophy of the muscularis of the right colonic wall.

Understandably, right colonic diverticulitis, which can occur at any age, almost invariably has a favourable course and never leads to free perforation with peritonitis or large abscesses.

Although relatively rare, it is crucial to make a correct diagnosis, since the clinical symptoms of acute RLQ pain may lead to an unnecessary operation for suspected appendicitis.

In 40% of patients it even leads to a right hemicolectomy because the surgeon during the operation assumes he is dealing with a colonic malignancy.

Although much more frequent in Asians, the diagnosis in the Western world is not rare: in a recent study one case of right colonic diverticulitis is seen for every 15 cases of sigmoid diverticulitis, and for every 30 cases of appendicitis [Oudenhoven].

US, if necessary complemented by CT, has characteristic features and prevents unnecessary surgery for this benign and self-limiting condition.

For proper understan?ding of the US images, it is vital to realize the dynamic sequence of the inflammatory process, where each stage of the disease has its own US image [Oudenhoven].

A dangerous pitfall is to mistake a fecolith in the base of an inflamed appendix for a case of cecal diverticu?li?tis.

Perforated Peptic Ulcer

LEFT: In the right upper quadrant wall thickening of the duodenal bulb is found. There are both transmural and extramural (arrow) gasconfigurations. The inflamed fat represents mesenterial and omental fat (fat) attempting -in vain- to wall off the perforation. RIGHT: In the right lower quadrant a large amount of debris-like peritoneal fluid is found.

LEFT: In the right upper quadrant wall thickening of the duodenal bulb is found. There are both transmural and extramural (arrow) gasconfigurations. The inflamed fat represents mesenterial and omental fat (fat) attempting -in vain- to wall off the perforation. RIGHT: In the right lower quadrant a large amount of debris-like peritoneal fluid is found.

The finding of pneumoperitoneum on a standing chest X-ray in combination with severe acute upper abdominal pain, is strongly suggestive for perforated peptic ulcer.

A laparotomy will usually follow without additional imaging.

In some cases however, symptoms of a perforated ulcer may be atypical and mimic those of appendicitis, in which case no chest X-ray is made.

In other cases of perforated ulcer free air is not present or not detectable.

In all those cases, US and CT may be of help.

Free air is easier detected by CT than by US, but US better defines the ulcer, demonstrates the free fluid, and can guide puncture of this fluid.

On the left a patient with a perforated duodenal ulcer.

In the right upper quadrant wall thickening of the duodenal bulb is seen.

There are both transmural and extramural (arrow) gasconfigurations.

The inflamed fat represents mesenterial and omental fat (fat) attempting -in vain- to wall off the perforation.

In the right lower quadrant a large amount of debris-like peritoneal fluid is found (right image).

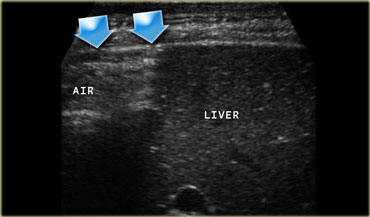

(Continued) On the left another image of the patient with the perforated duodenal ulcer. In the left decubitus position free air can be seen to collect between liver and the lateral abdominal wall.

In peptic ulcer US visualizes asymmetrical thickening of the duodenal wall which contains a constant air configuration reaching from the duodenal lumen to the periphery of the wall or even penetrating into the adjacent inflamed fat.

Right decubitus position will allow gastric fluid- which is usually present in peptic ulcer disease- to proceed to the duodenum, enabling a better visualization of the ulcer.

In case of perforation, an air-track can be found from the ulcer to the peritoneal cavity usually in ventral or cranial direction.

Free air is best demonstrated in the left decubitus position between liver and right abdominal wall.

A lot of free fluid is usually present which contains airbubbles and foodparticles.

Puncture reveals turbid or purulent fluid