US of the GI tract - Normal Anatomy

Julien Puylaert

Medical center Haaglanden in the Hague and Academical Medical Center in Amsterdam, the Netherlands

Publicationdate

Press ctrl+ for larger images and text on a PC or ⌘+ on a Mac.

Most images can be enlarged by clicking on them.

For critical comments and additional remarks: [email protected]

Normal anatomy

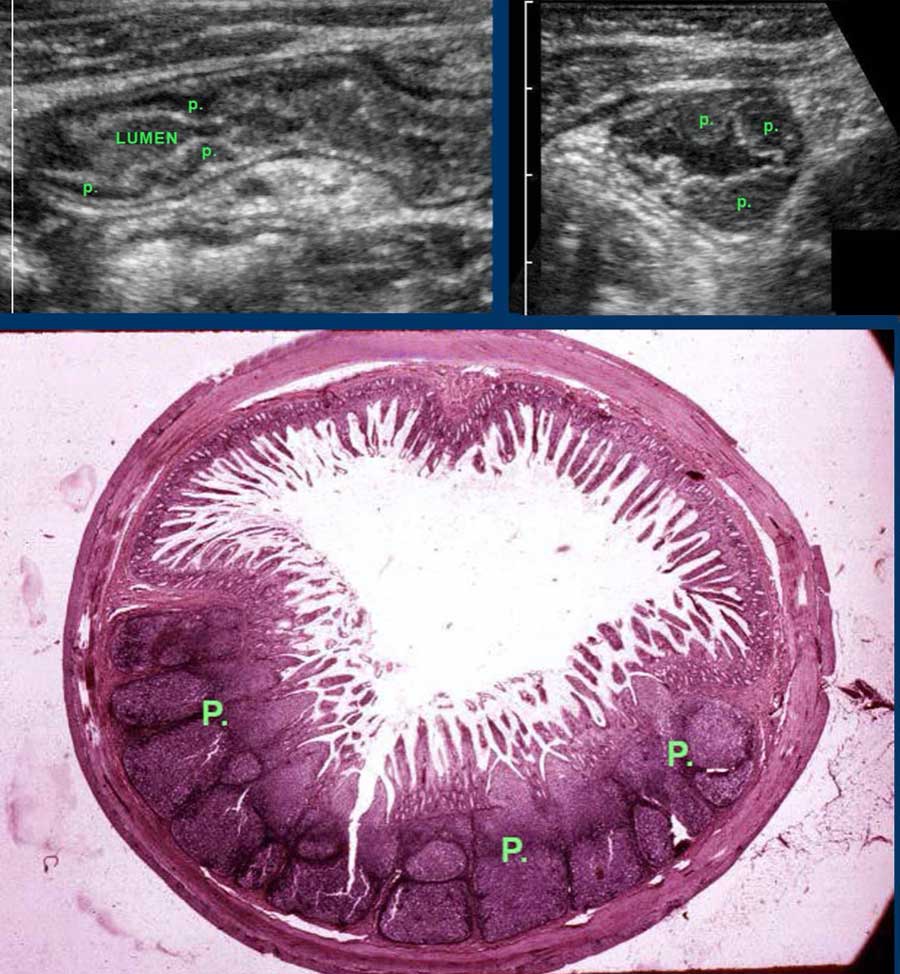

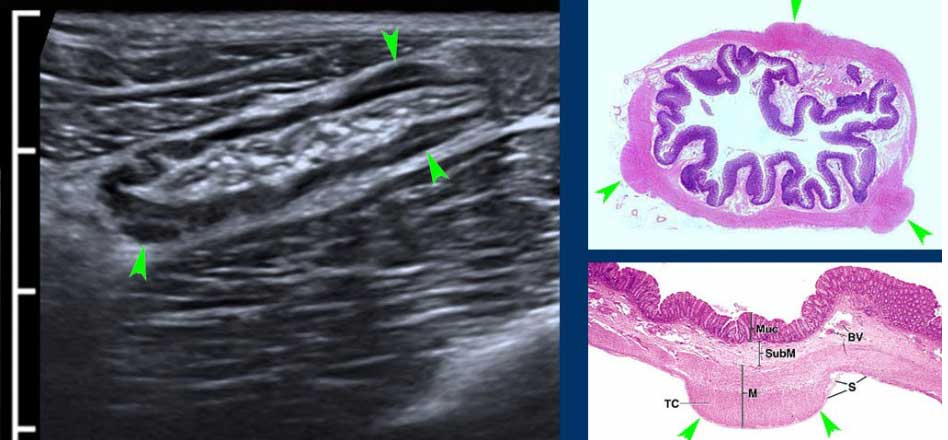

Histology of the GI tract

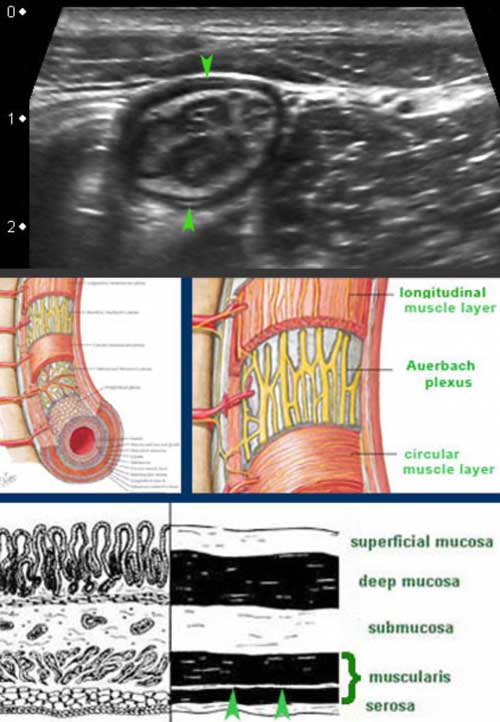

From inside to outside the layers of the small bowel are the mucosa (M.), the submucosa (S.M.), the circular muscle layer (C.M.), the longitudinal muscle layer (L.M.) and the serosa (S.)

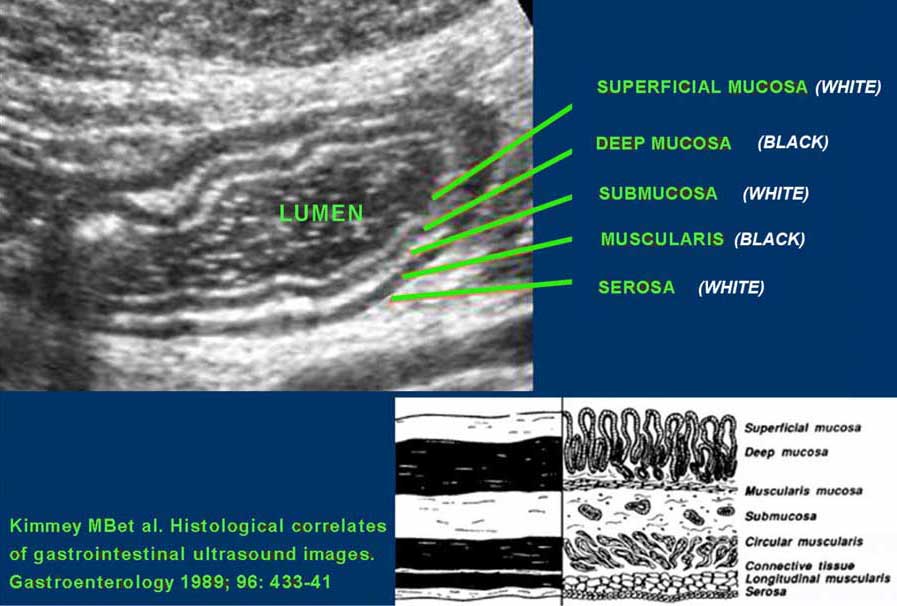

US fingerprint of the normal GI tract

The classic five-layer-US-structure of the bowel wall is easiest apprehended by studying the wall of the fluid filled stomach.

The layers, starting from inside to outside, are hyper-hypo-hyper-hypo-hyper-echoic or white-black-white-black-white.

The US architecture of the wall is essentially the same from the stomach to the rectum.

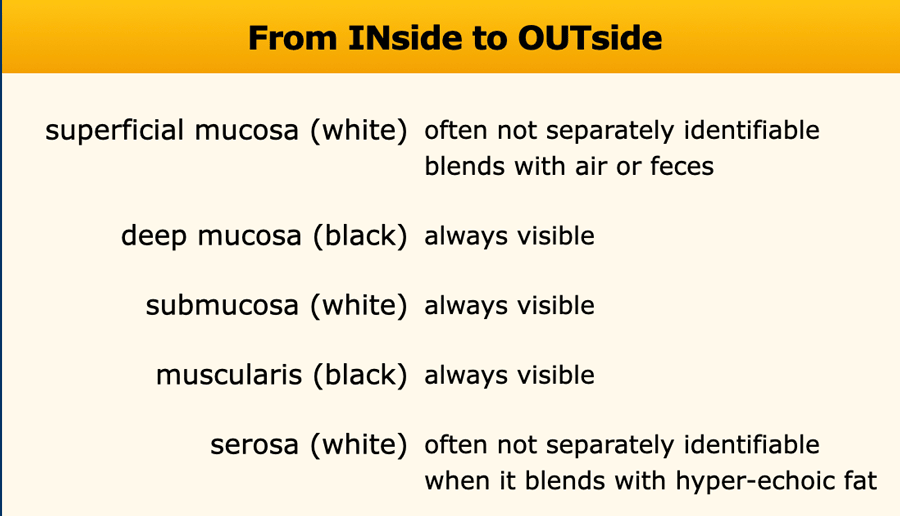

Superficial mucosa

The superficial mucosa is brightly hyperechoic, due to mucus and very tiny air-particles caught between the small intestinal villi.

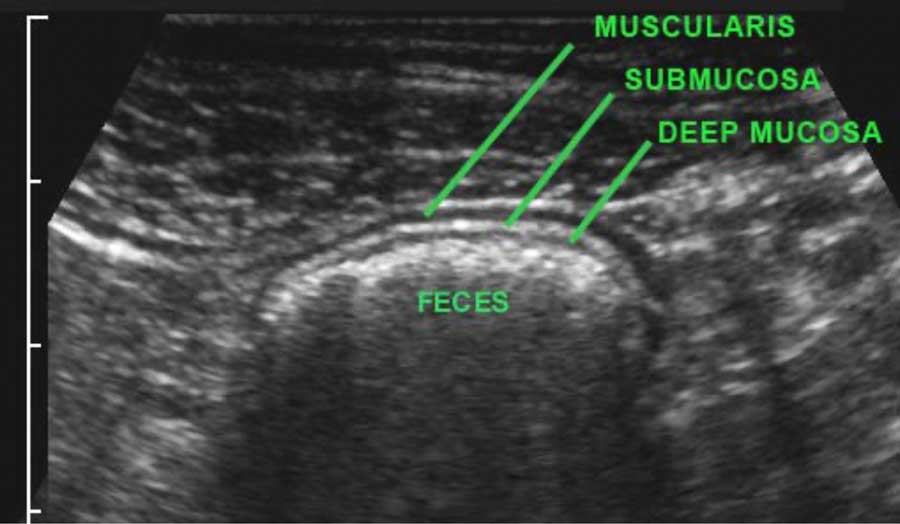

It is not separately identifiable, when it blends with hyperechoic feces, as in this US image of the colon.

The outer white serosa can only be identified when there is ascites.

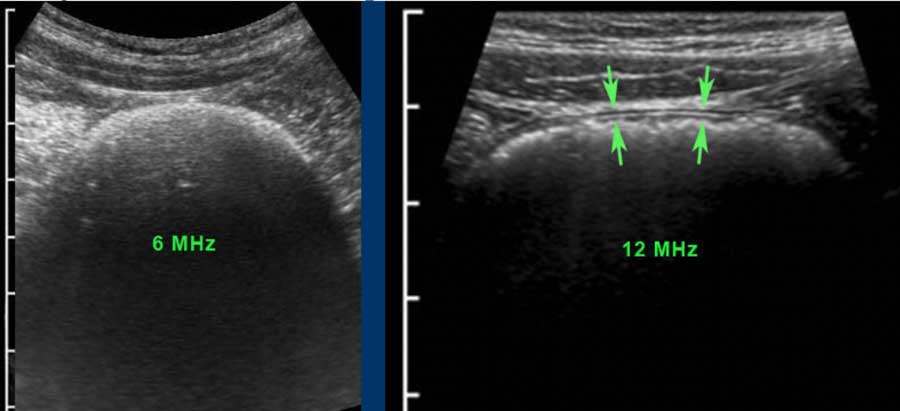

When a high frequency probe is used, the middle three layers, deep mucosa, submucosa and muscularis (black-white-black) are always visible.

In this patient with severe coprostasis, the three-layer wall architecture could only be recognized with a 12 MHz probe.

Deep Mucosa

The deep mucosa is hypoechoic and has a variable thickness. It represents the packed glandular tissue and - for only a small part- the muscularis mucosae.

Especially in the terminal ileum of children and young adults, prominent echolucent lymphoid tissue is found in the deep mucosa.

These so-called Peyer’s patches (p) may be impressively large and asymmetrical.

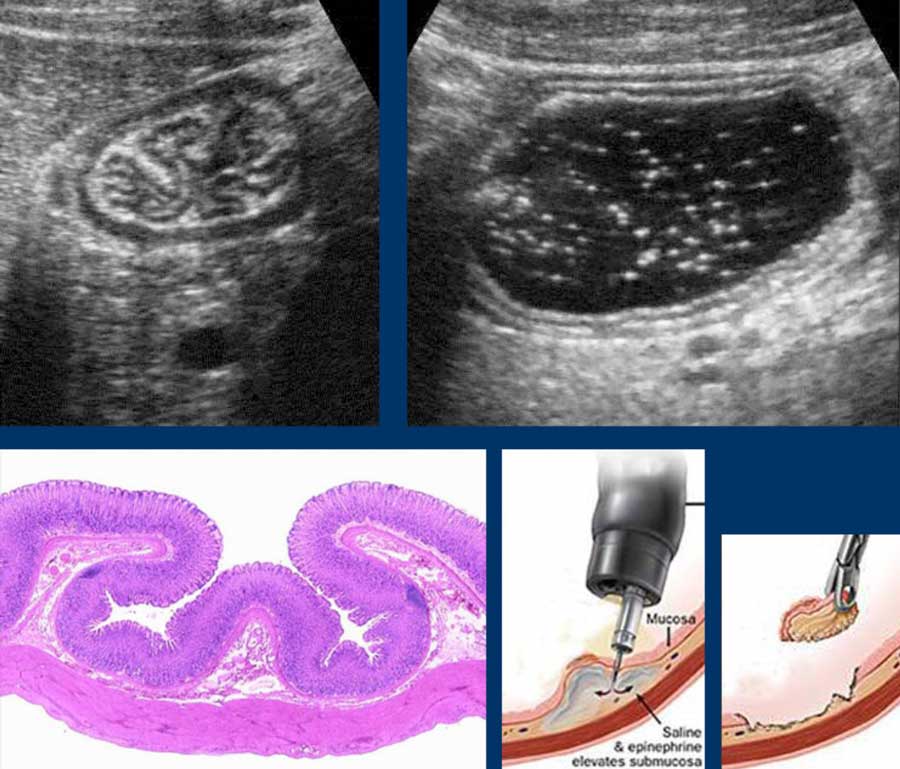

Submucosa

The submucosa contains vessels, nerves and fat and is hyperechoic due to abundant loose connective tissue.

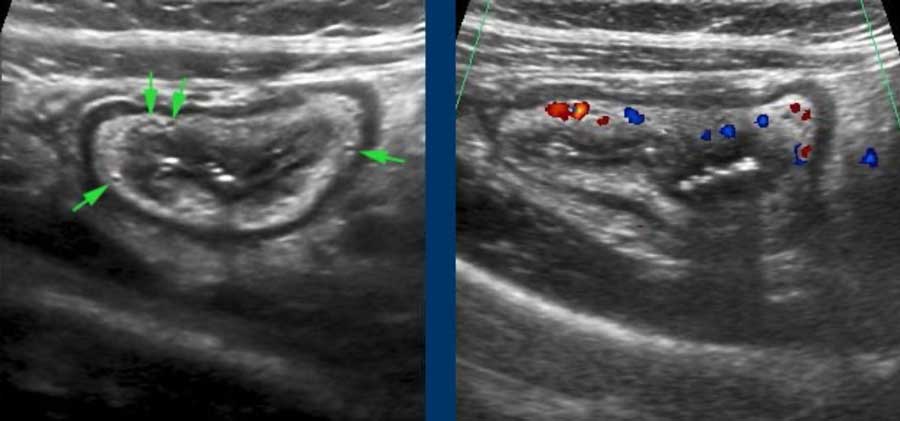

In this patient with ulcerative colitis, prominent vessels (arrows) in the submucosa are visualized and proven with color Doppler in the right image.

The submucosa “loosely connects” the mucosa with the muscularis, and during contraction, the submucosa can be seen to follow the mucosal folds (left upper).

After drinking water, the mucosa and submucosa are stretched and unfolded (right upper).

This loose connection also explains why gastroscopical biopsies can be taken unpunished, especially when the submucosa is injected with saline first (right under).

Muscularis

The muscularis is hypoechoic due to muscular tissue and as outer black layer is easy to identify.

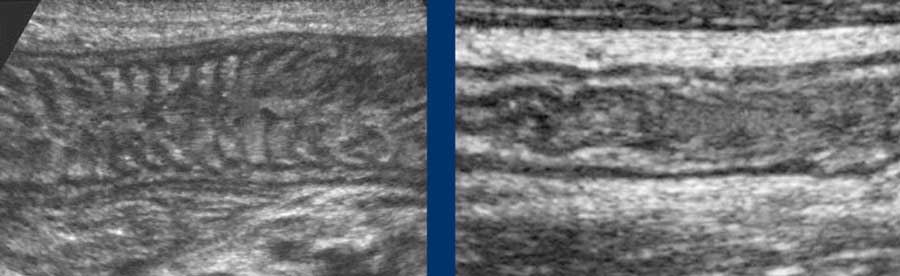

It consists of two layers: an inner circular muscle layer and an outer longitudinal muscle layer, which cooperate to produce peristaltic movements.

These two muscular layers are separated by a thin layer of connective tissue, containing the neural tissue of the Auerbach plexus.

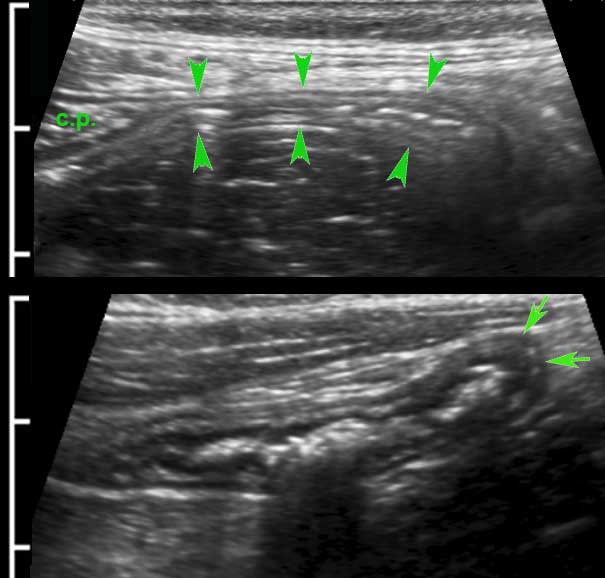

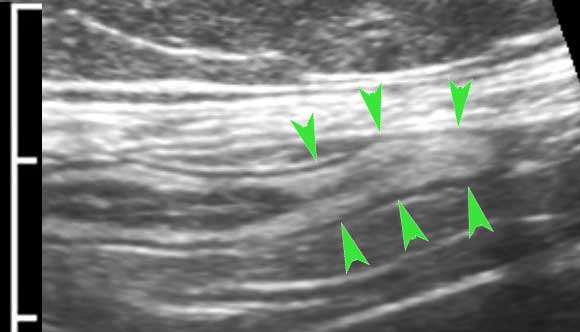

This thin layer (arrowheads) is hyperechoic on US and can be seen in the small bowel of lean patients.

Although clinically not relevant, the separate US identification of the Auerbach plexus, underlines the high resolution of US compared to CT and MRI.

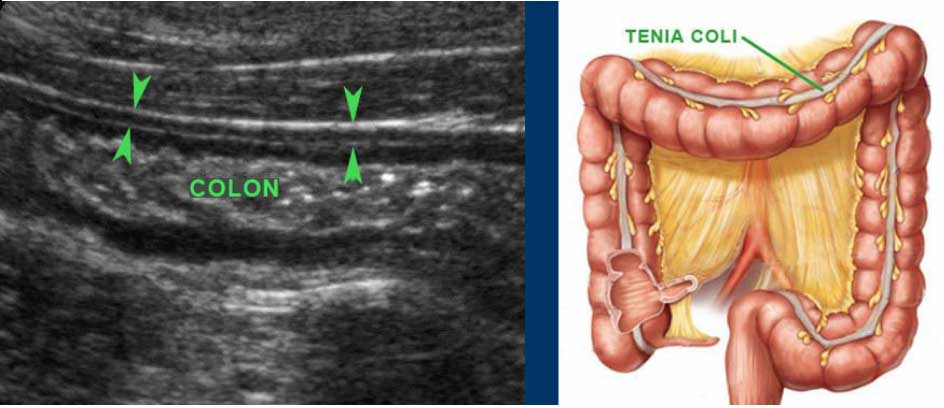

The muscularis of the large bowel is different from that of the small bowel.

The longitudinal muscle layer is limited to three longitudinally oriented bands, known as teniae coli. In the empty, compressed colon in thin patients, these three teniae (arrowheads), can often be identified by US as a local thickening of the muscular layer, separated from the circular layer by a thin hyperechoic line.

In this longitudinal view only one tenia coli (arrowheads) is identified.

Serosa

The serosa or visceral peritoneum is the thin but tough outer hyperechoic layer, which usually blends with the hyperechoic fatty tissue of mesentery and omentum, surrounding the bowel.

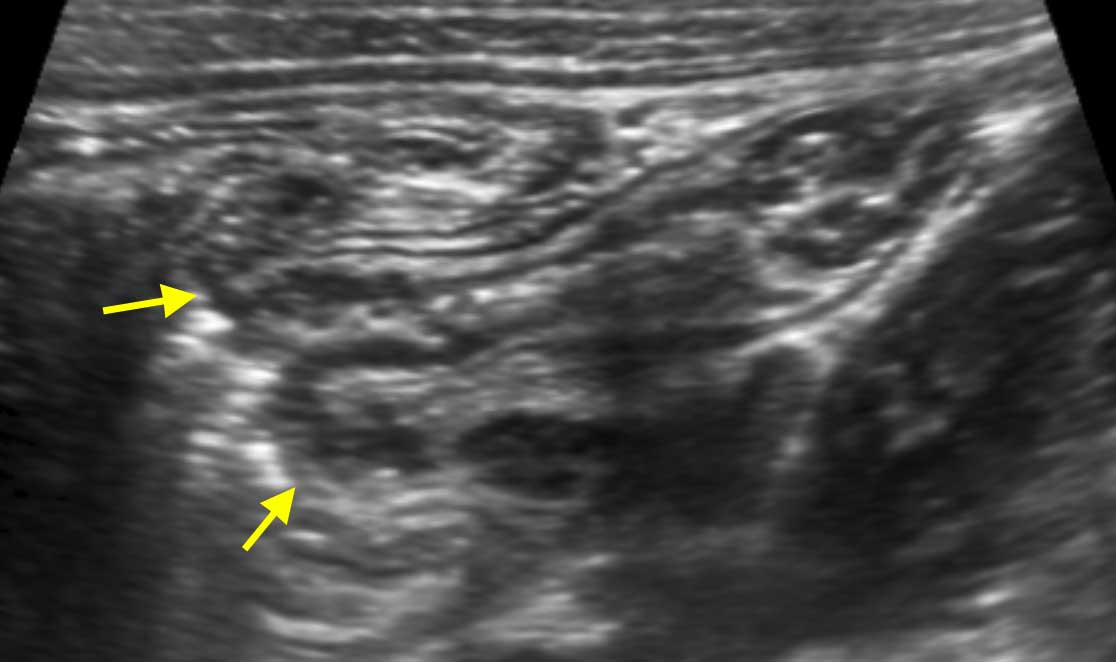

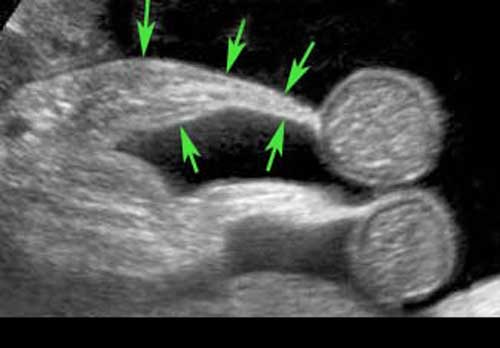

If there is intraperitoneal fluid, the hyperechoic serosa (arrow) can be separately identified, as in these ileal loops.

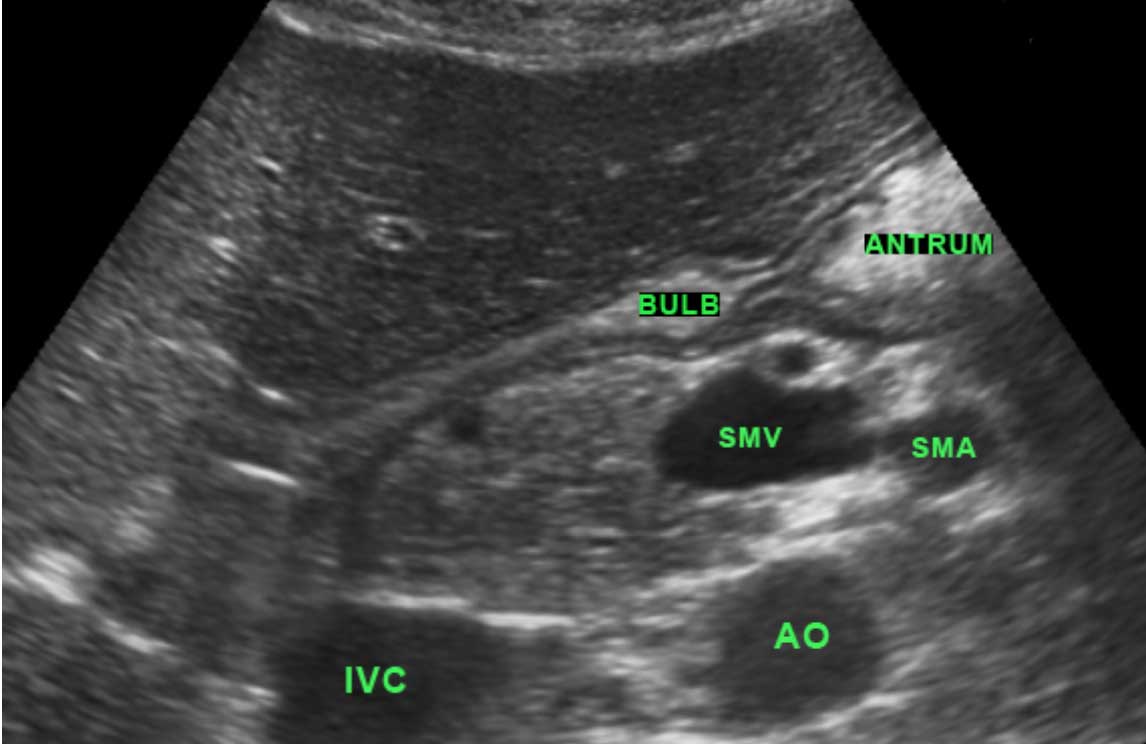

Stomach

In most patients referred for US, the stomach is empty, either because they have been asked not to drink too much prior to the examination, or because they have vomited associated with their acute abdominal problem.

If the stomach is fluid-filled and the patient denies previous drinking, this is a relevant finding.

It may be mechanical obstruction, gastric paresis or hypersecretion with stasis due to active peptic ulcer disease.

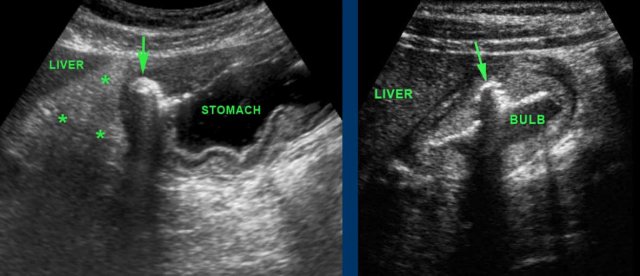

Antrum and duodenal bulb are the parts of the stomach best identified by US.

The pylorus is recognized as a local thickening of the muscularis distally to the antrum.

The wall of the duodenal bulb is thinner than that of the stomach.

Gastric fluid can be used to improve visualization of the antrum and duodenal area, by turning patients on their right side: air rises to the gastric fundus, and fluid enters antrum and duodenal bulb.

This is especially helpful in adults with peptic ulcer disease.

The left image shows a gastric ulcer (arrow).

Note the loss of layer structure in the ventral stomach wall and the inflamed fat (asterisks) representing the omentum and mesentery, trying to wall-off the imminent perforation from this deep penetrating gastric ulcer.

The right image shows an ulcer (arrow) in the ventral wall of the fluid-filled duodenal bulb.

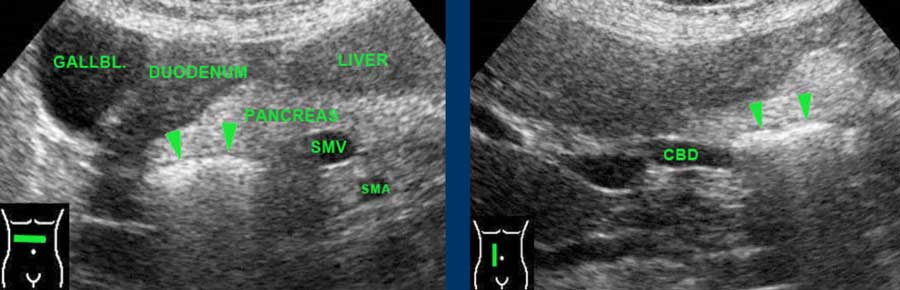

Descending and horizontal duodenum are rarely accessible for US.

When specifically looked for, large air-filled duodenal diverticula, present in 10-15 % of the normal population, can be identified.

They present as a (curvi)linear reflection within the pancreatic head.

Note that these patients often have a wider common bile duct than normal patients.

Small bowel

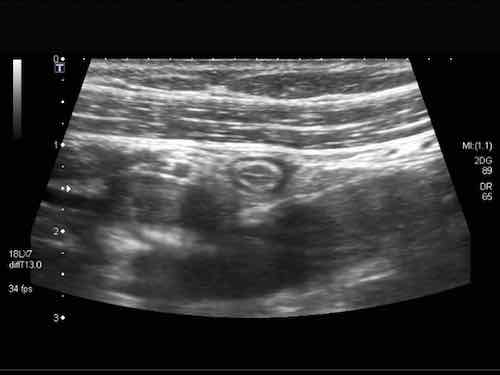

The normal small bowel is easily visualized by US and is recognized by continuous and vivid peristalsis, even if the lumen is empty.

Note multiple small round echolucencies with a hyperechoic border within the bright submucosa.

These represent normal 0.4 – 0.5 mm vessels.

Note also the thin hyperechoic line within the muscularis, representing the connective tissue separating the longitudinal and circular muscle layer, containing the Auerbach plexus.

Normal small bowel in the longitudinal plane.

Jejunum

The jejunum (left image) is mainly located in the LUQ, and contains more Kerckring’s folds (valvulae conniventes) than the ileum (right image), which is more located in the RLQ.

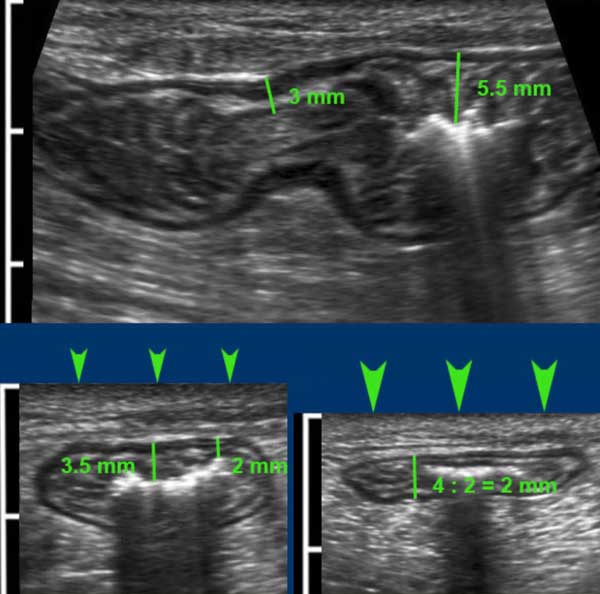

Measuring bowel wall thickness with US is difficult because thickness changes with peristaltic movements.

In this individual, measurements in the longitudinal plane (upper panel) and in the axial plane during light compression (left under) vary considerably, but during moderate compression (right under) measurements are well reproducible and accurate.

As the thin hyperechoic serosa is rarely discernible, bowel wall thickness is measured from the outer contour of the ventral muscularis to the outer contour of the dorsal muscularis, and then of course, divided by two.

Normally, single small bowel wall thickness during compression is about 1.5 - 2.5 mm.

Measuring bowel wall thickness by US this way is reproducible and comparable to what surgeons do with their fingers during laparotomy to decide whether small bowel is abnormal.

In contrast to most diseased bowel loops, normal small bowel loops are well compressible during relaxation.

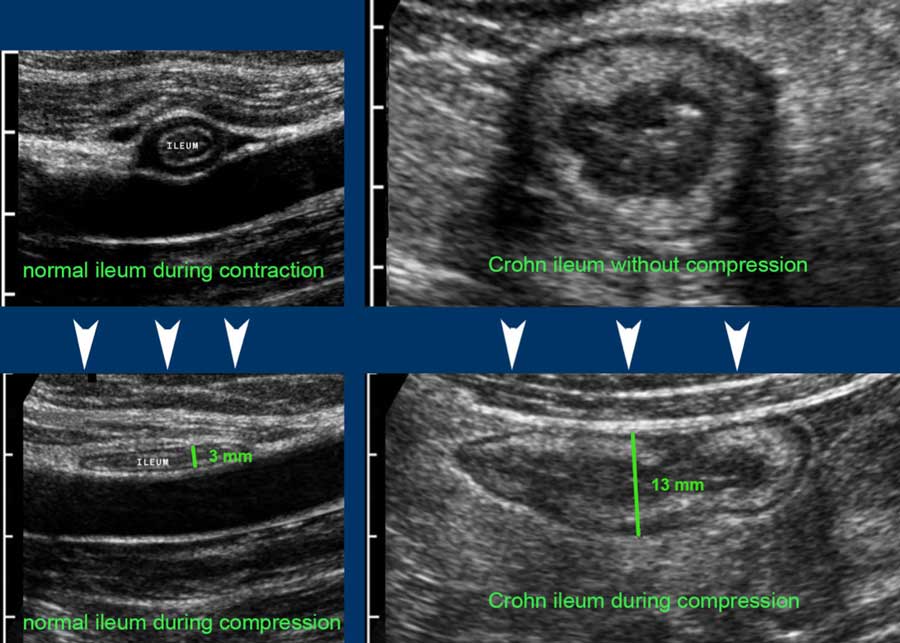

Compare a normal terminal ileum (left) and a Crohn’s ileum (right), without compression (upper images) and with compression (lower images).

Note the same cm-scale in all four US-images.

Single wall thickness in the normal individual is 1.5 mm, in the Crohn patient 6.5 mm

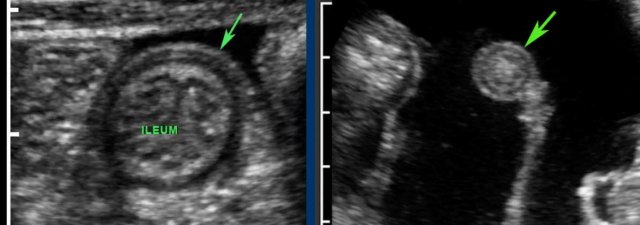

Terminal ileum

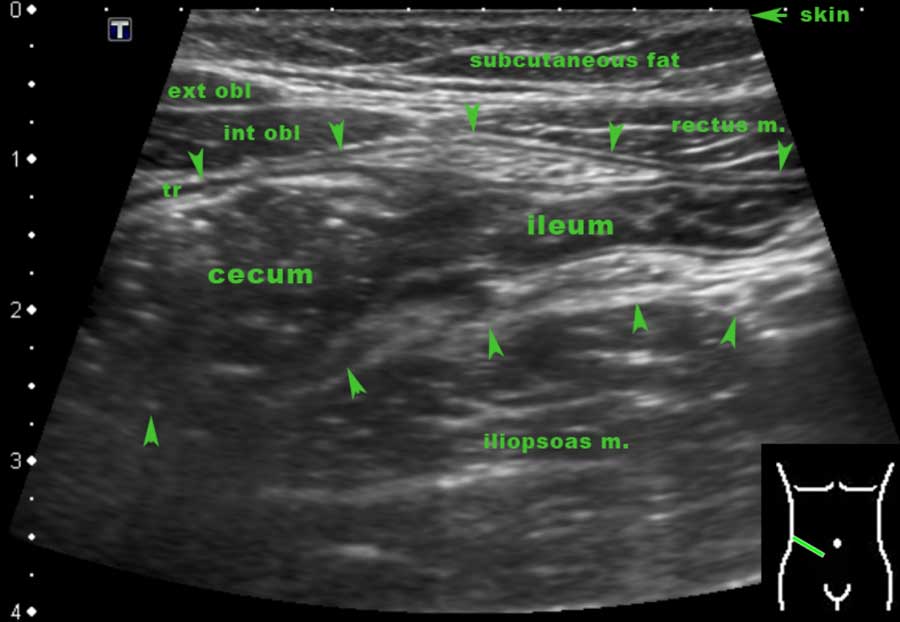

The terminal ileum can often be identified separately due to its specific location and course from the pelvis toward the paracolic gutter.

The actual discharging of the normal terminal ileum into the cecum can only be seen in thin patients with an empty cecum.

The location of the ileocecal valve may vary widely, but its average location is right of the umbilicus.

Note the lymphoid hyperplasia of the Peyer’s patches in the terminal ileum.

More frequently the terminal ileum can be followed until it disappears into the feces-filled cecum.

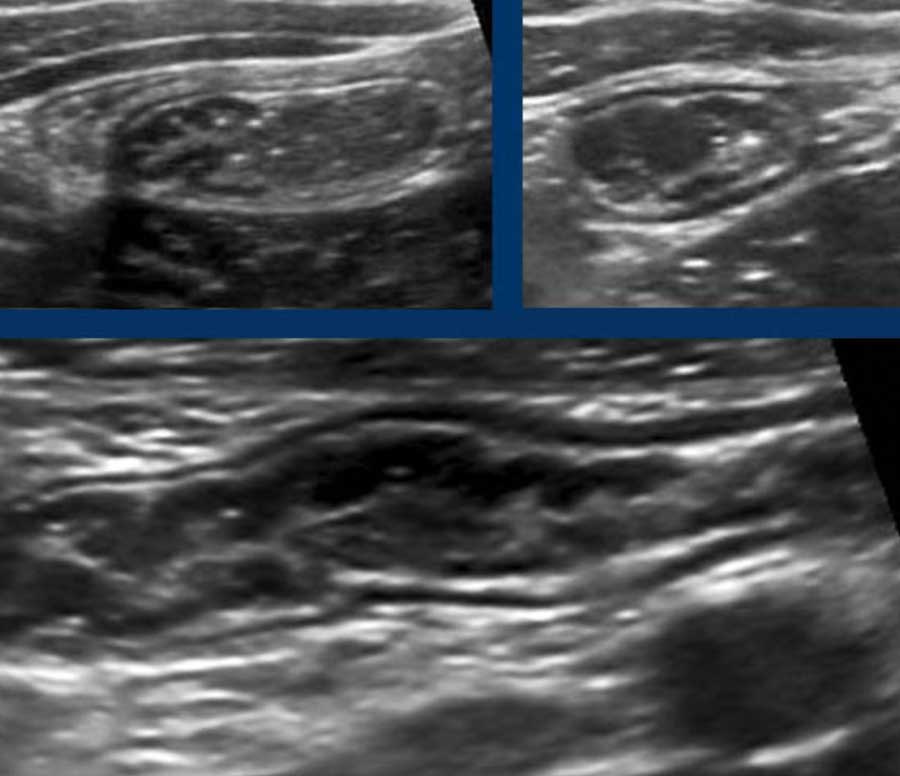

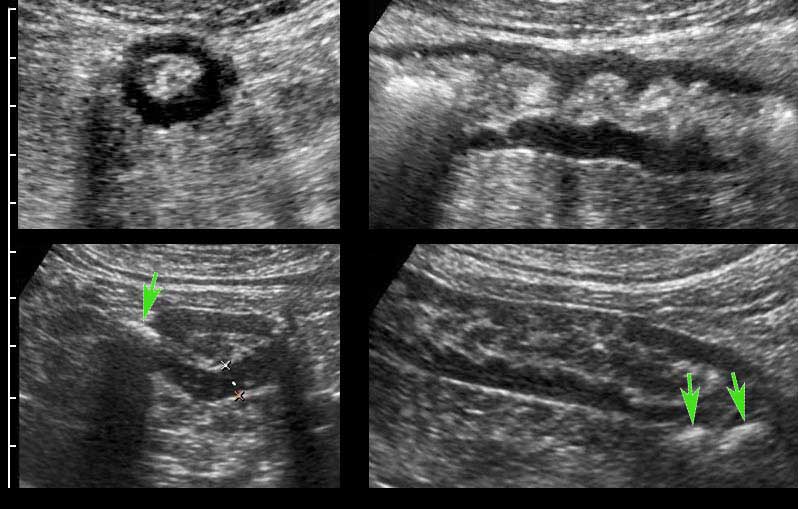

These are images of the terminal ileum in three different children and young adults with large Peyer’s patches presenting as asymmetrical, hypoechoic thickening of the deep mucosa.

With every new antigen, the lymphoid tissue becomes reactivated.

In young patients both mesenteric lymph nodes and Peyer’s patches are –also in absolute dimensions- much larger than in adults.

The stimulated lymphoid tissue in youngsters not only results in prominent Peyer’s patches in the terminal ileum and enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes (left under), but also in a thickened deep mucosa of the appendix (right under).

Note that the –sometimes polyp-like- protrusions (right upper), may act as lead-point in the classic ileocecal intussusception in young children

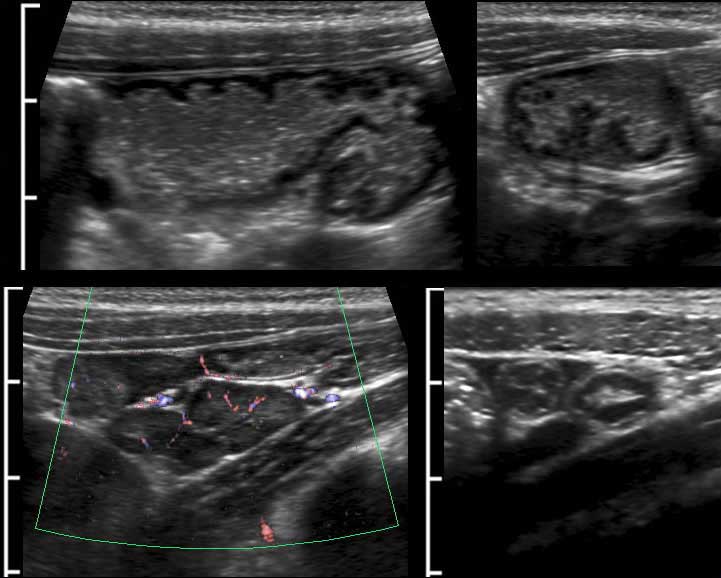

Intussusception

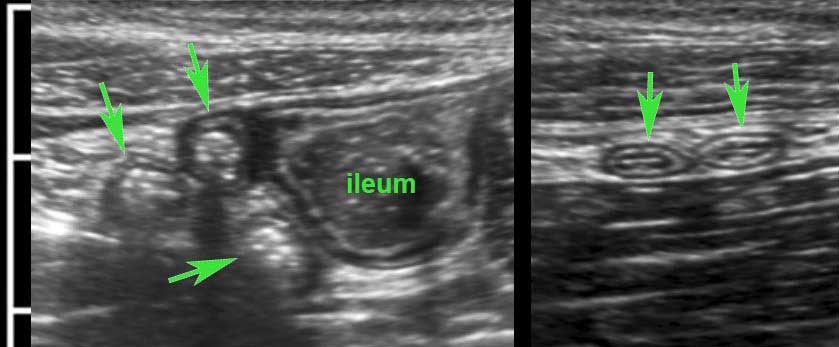

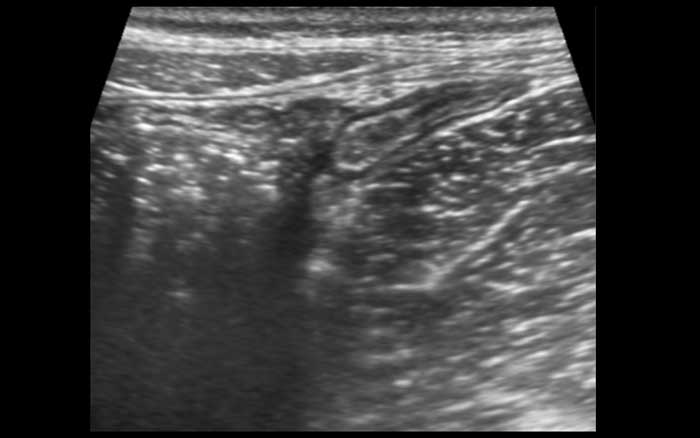

Here the US image in a 2 year-old child with intermittent ileocecal intussusception, examined in between attacks.

The ileum with abundant Peyer’s patches shows prolaps into the cecum.

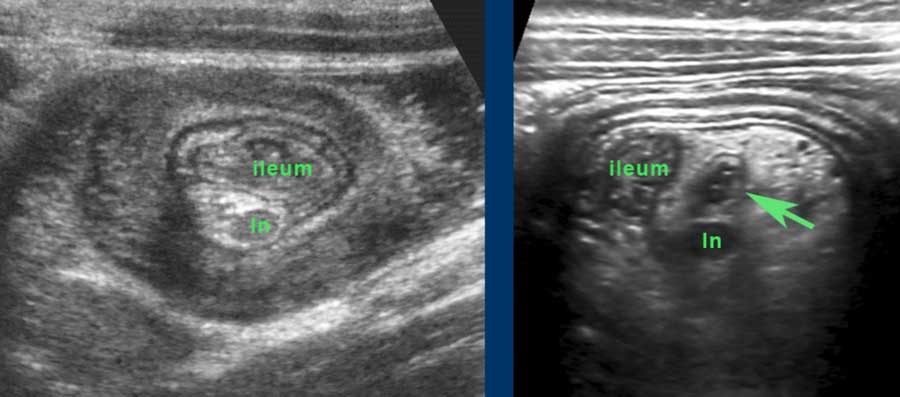

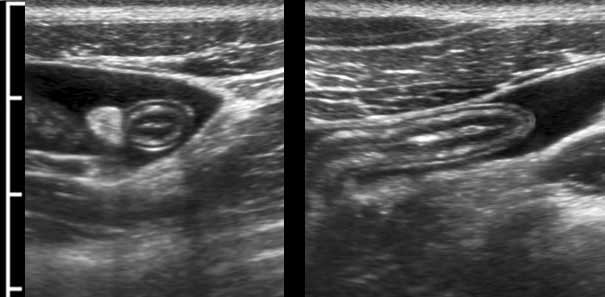

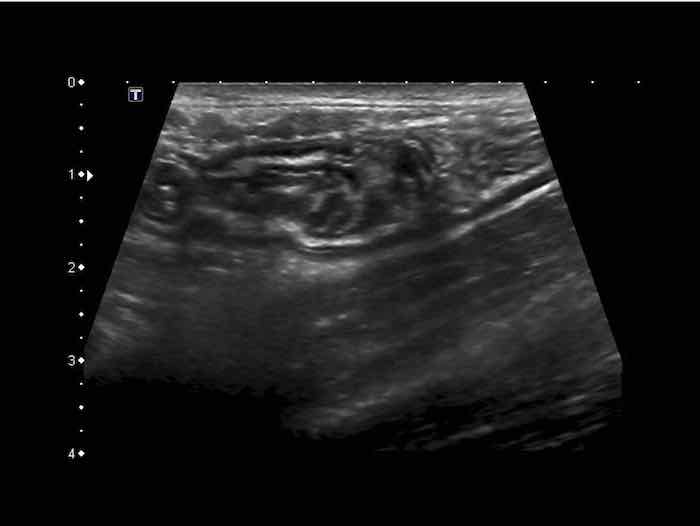

Classic US image of ileocecal intussusceptions in two different children.

In both, the intussuscepted ileum is asymmetrically positioned within the intussuscipiens, due to the hyperechoic fatty mesentery, attached to the ileum and following the ileum, when pulled in.

Within the mesentery US shows an enlarged mesenteric lymph node (ln) in both.

These nodes are enlarged as part of the general lymphoid hyperplasia and are not localised in the ileal lumen.

Therefore it is not the primary lead point. In the patient on the right, the appendix (arrow) is pulled in also.

Note the multi-layered aspect of the ventral wall of the intussusception complex, representing three folded bowel wall layers.

Although the lymphoid tissue in the terminal ileum is most impressive in the young child, it may be found until the age of 20 years.

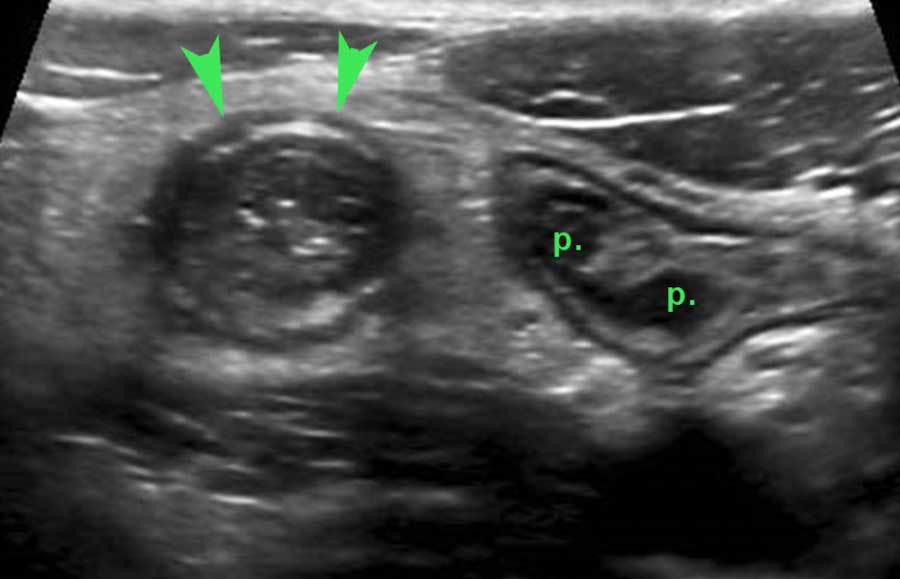

In this young man of 15 years with an acute appendicitis (arrowheads), there are still prominent Peyer’s patches (p.) in the deep mucosa of the terminal ileum.

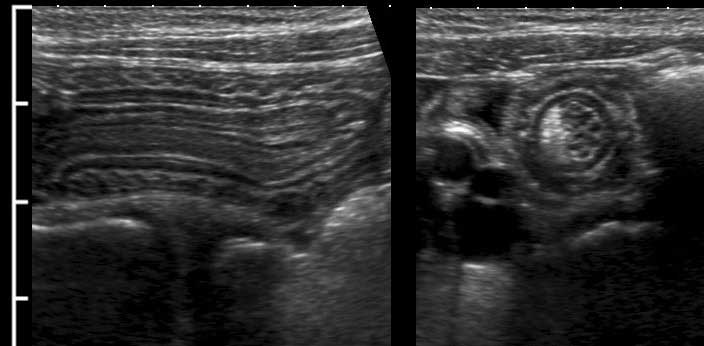

During US examination, it is not unusual to witness a small, transient, ileo-ileal intussusception.

Apart from lack of symptoms, these can be discriminated by US from the real symptomatic intussusception, because they are smaller (< 2 cm), compressible, transient and have no lead point.

These transient intussusceptions may be associated with celiac disease and it is important to exclude this condition with blood tests.

Omentum, mesentery and lymph nodes

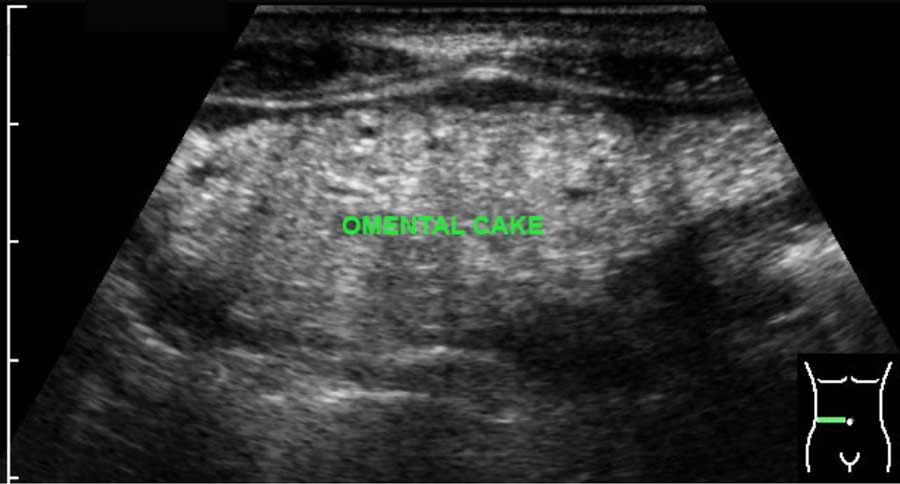

The normal omentum is usually not separately visible.

When it is thickened e.g. in malignant or, more rarely, in tuberculous peritonitis, it may present as omental cake, especially if there is concomitant ascites.

US can also visualize the omentum (arrowheads) in segmental omental infarction, in which the omentum is swollen due to venous hemorrhagic infarction.

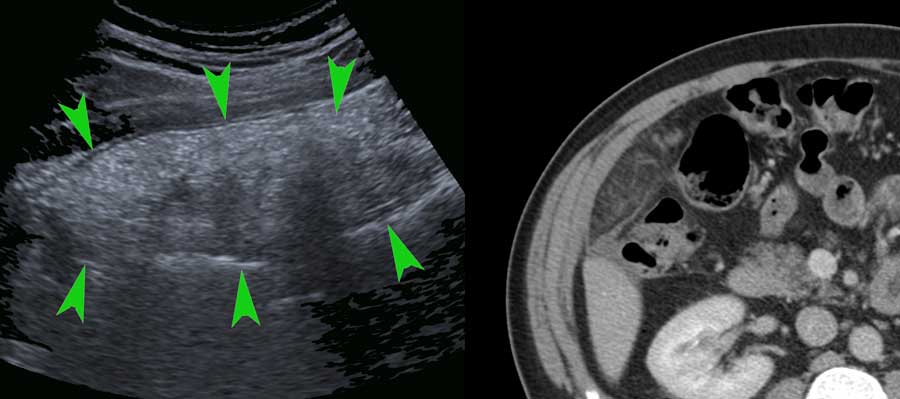

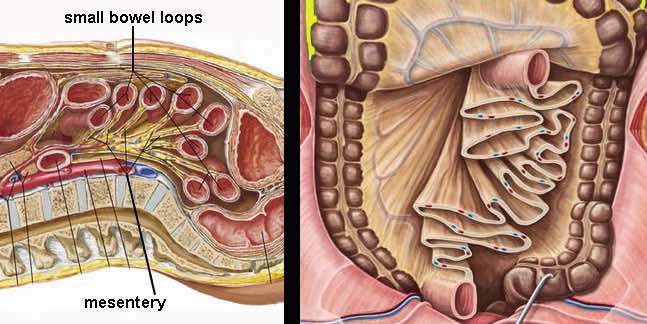

The small bowel is attached to the mesentery which is folded like a fan.

The mesentery contains a variable amount of fat, and the folded, fatty mesentery has a multi-layered aspect, especially when compressed during US.

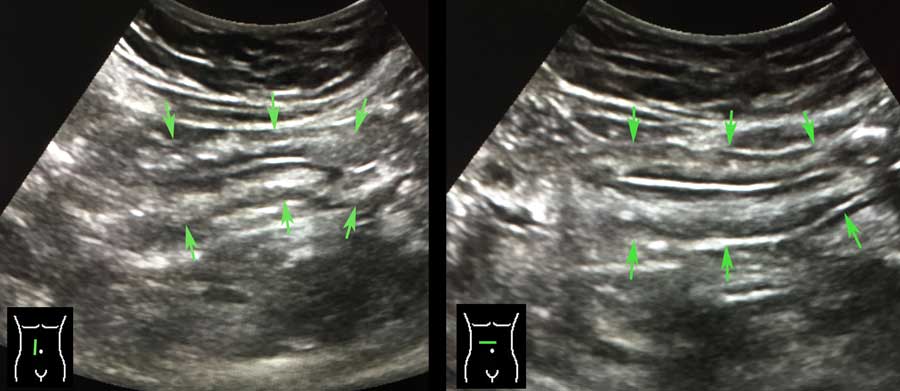

The normal mesentery (arrows) in thin patients is only visible when there is ascites.

In the obese, the mesentery contains a lot of fat and can be visualized as a well-compressible, flat, multi-layered structure.

In one plane this may simulate a thickened bowel wall (arrows in left image) .

Turning the probe 90 degrees (right image), it is immediately recognized as a flat structure (arrows).

At the edge of the fatty mesentery, vivid peristalsis in two small bowel loops can be visualized.

Click image for animation.

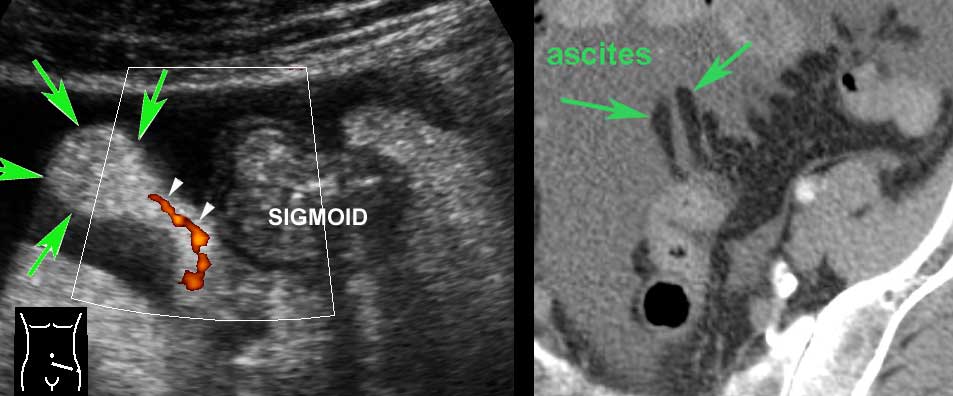

Epiploic appendages

Next to mesentery and omentum, also the properitoneal fat is part of the intra-abdominal fatty tissue, as are the epiploic appendages (arrows).

They have a fragile blood supply (white arrowheads) , prone to hemorrhagic infarction (epiploic appendagitis).

Normal epiploic appendages are only visible on US and CT in case of ascites.

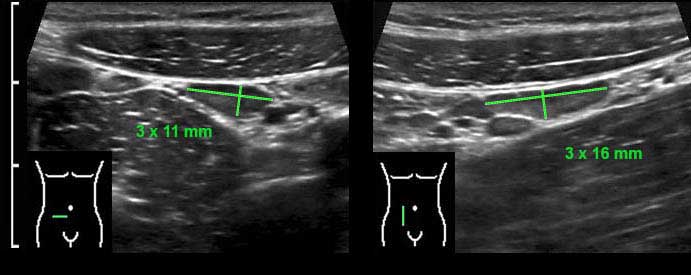

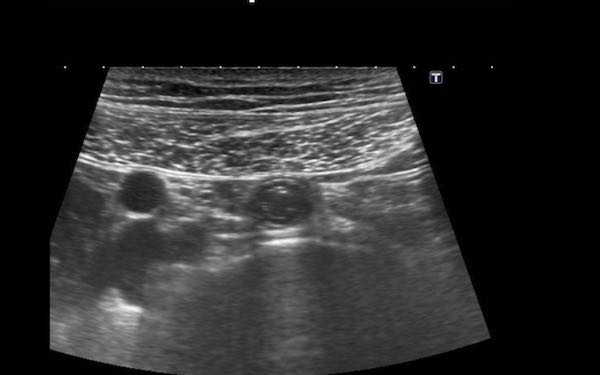

Within the mesentery the mesenteric lymph nodes can be visualized, predominantly in the region right of the umbilicus.

During graded compression in thin patients the nodes appear very close to psoas muscle and iliac vessels.

The dimensions of the normal mesenteric lymph node are variable, in this case the dimensions in three planes are 3 x 11 x 16 mm.

Although transverse and longitudinal diameters may even be larger, the shortest axial diameter in adults should not exceed 5 mm.

In case of enlarged mesenteric lymph nodes, it is -initially- only the shortest axial diameter that increases.

Therefore, to decide whether a node is normal or abnormal, measuring the shortest axial diameter suffices.

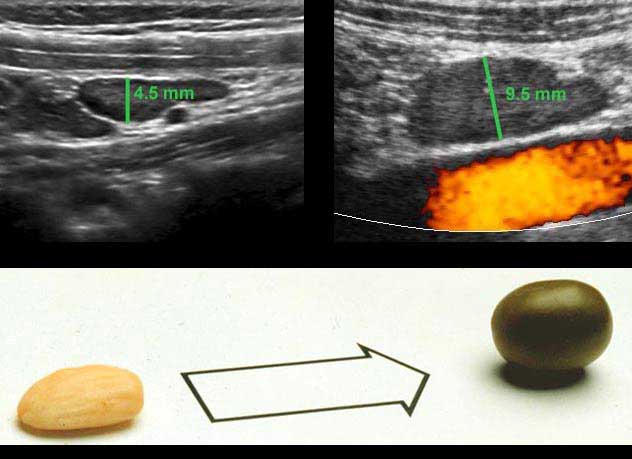

The shape of a normal versus an abnormal mesenteric lymph node, is that of an almond versus an olive. In children, especially those of 5 to 10 years old, the mesenteric lymph nodes are much larger than in adults, with short axial diameters up to 10 mm.

These large mesenteric lymph nodes in children, may be associated with viral infections, but can be found in otherwise healthy kids.

Normal mesenteric lymph nodes have a relatively hyperechoic center and a lobulated, echolucent peripheral zone, representing the germinal centers.

Appendix

An experienced sonographer can identify the entire normal appendix -including the blind end- in about 30 % of adult patients and 80 % of children.

US visualization of the entire normal appendix, excludes appendicitis.

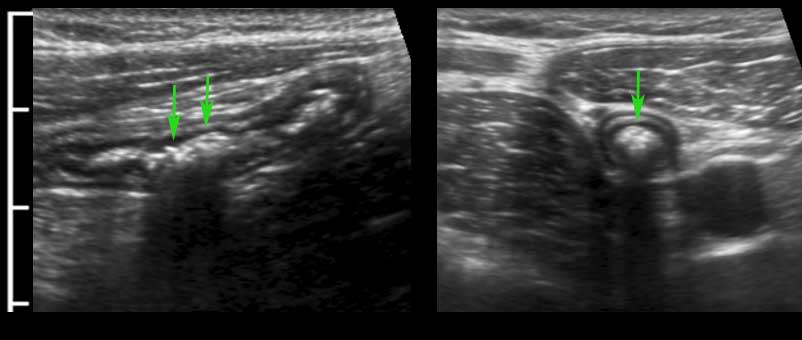

The normal appendix has the same layers as in normal bowel wall. In this young woman all five layers are visible including the serosa, thanks to a little intraperitoneal fluid.

Note the empty lumen and the normal triangle-shaped hyperechoic meso-appendix.

To compress the appendix, a rather firm underground is mandatory like iliac artery, psoas muscle or vertebral body.

The normal appendix (arrowheads) is discriminated from small bowel by its location, its size, its absence of peristalsis, its attachment to the cecal pole (c.p.) and its blind distal end (arrows).

The blind end of the normal appendix is firmly demonstrated using a “mini-clip”.

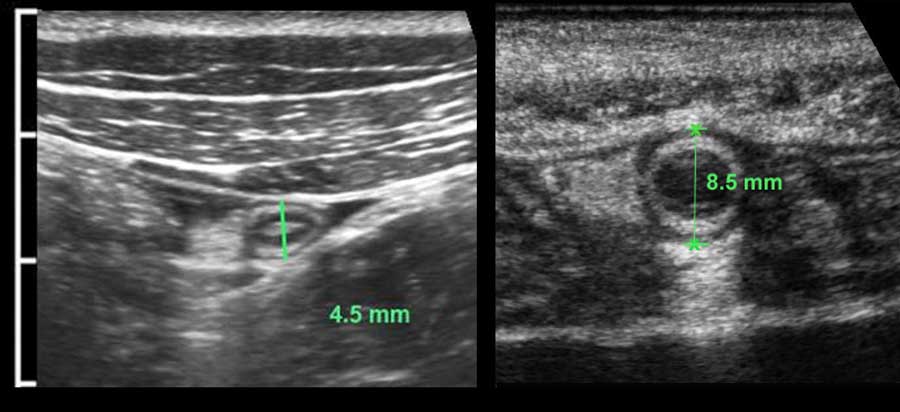

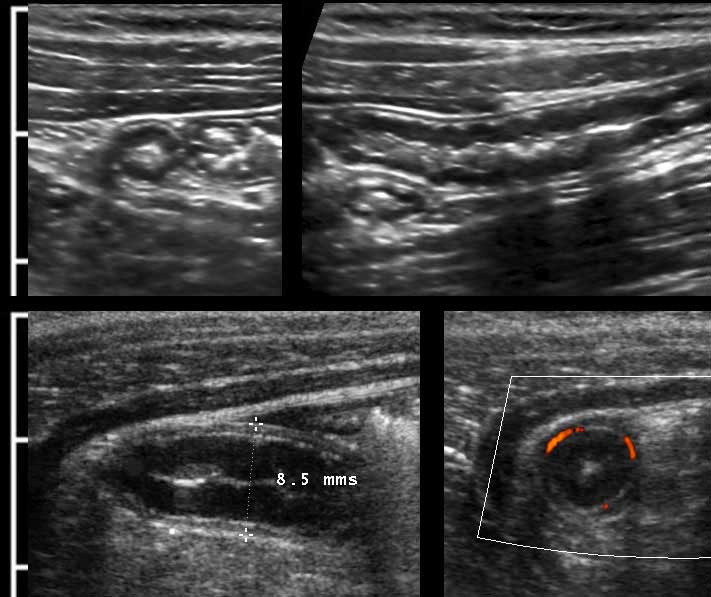

The US diameter of the appendix is measured the same way as bowel: during moderate compression from outer contour of the ventral muscularis to the outer contour of the dorsal muscularis.

Thus measured, the diameter of this normal appendix (left) is 4.5 mm and of this inflamed appendix (right) 8.5 mm.

In many textbooks a cut-off value of 6 mm is reported, however this is not a reliable value.

Rettenbacher (Radiology 2001; 218: 757-62) did a large study and found that the diameter of the normal appendix was 6 mm or larger in 27 % of cases, with a range of 2-13 mm.

The US criteria of appendicitis will be discussed in a special chapter on appendicitis.

CT measurements overestimate the appendix diameter compared to US.

In the literature the mean CT diameter of a normal appendix is 6.5- 8 mms (range, 3 to14 mm).

The explanation for this discrepancy may be that on CT:

- The serosa is included in the measurement

- There is no compression involved.

- Also, the contours of the appendix on CT are rather fuzzy, making measurements less reproducible.

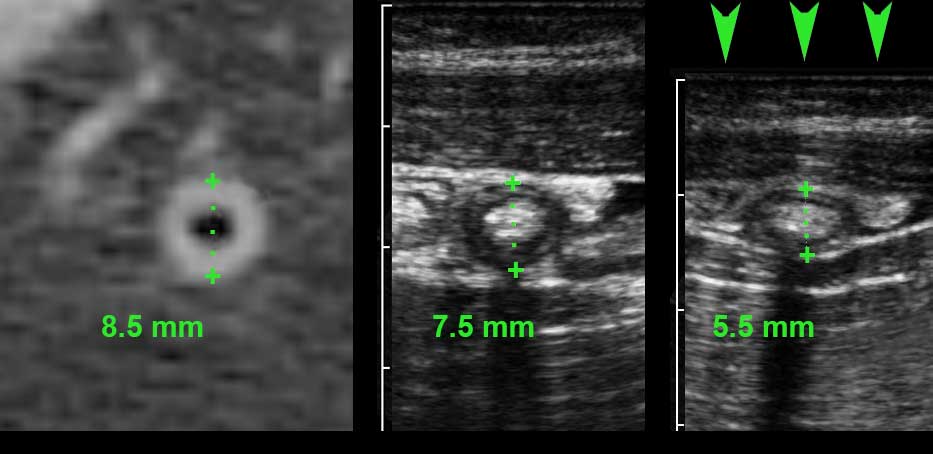

The left panel here shows a CT of a normal, feces-filled appendix of 8.5 mm.

The middle panel is a US image of a comparable normal appendix in a different patient measuring 7.5 mm, the right panel shows that same appendix during compression (5.5.mm).

The literature indicates that the US diameter of the normal appendix is 6 mms or less in 73 % of cases.

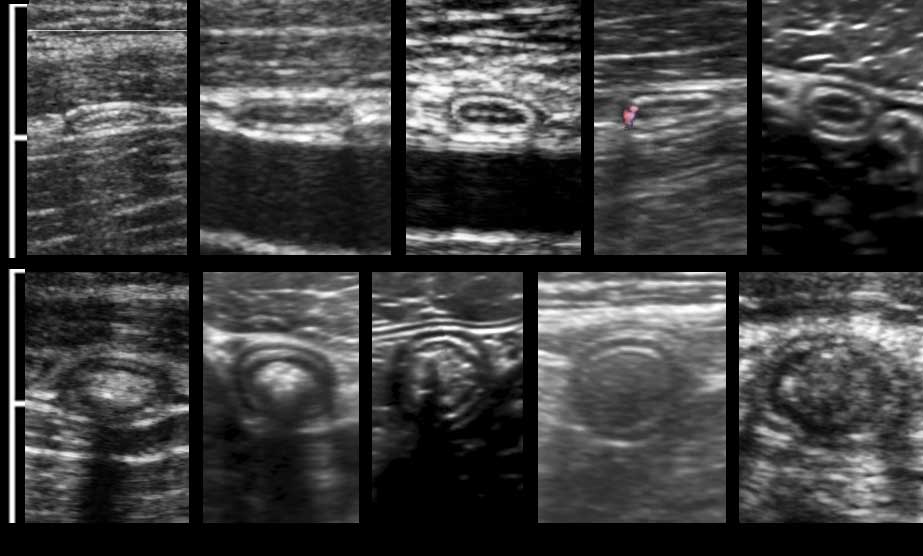

Here you see the normal appendix during compression in ten different patients with AP-diameters varying from 2-10 mm (Note the same cm-scale).

In the lower five, the lumen is filled with fecal material of various reflectivity, which make the appendix less compressible.

The most important discriminating feature indicating appendicitis is inflamed fat, followed by diameter, non-compressibility, hyperemia and a fixed position.

There are of course additional US features in advanced appendicitis, as fluid collections and loss of layer structure, but in these cases it is clear that the appendix is inflamed.

More rarely, some intraluminal fluid is seen, in which case the appendix is easily compressible.

Not rarely, the blind ending tip (arrowheads) of the normal appendix has no lumen due to fibrosis.

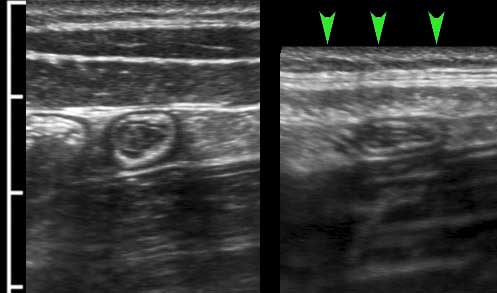

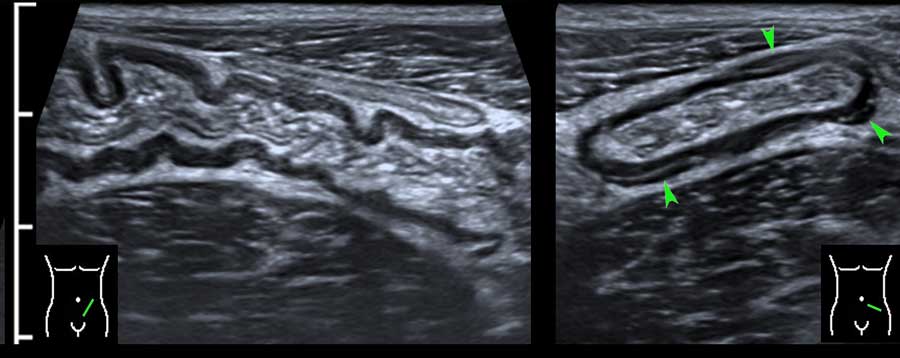

Unlike the inflamed appendix, the normal appendix has no fixed position and during the US examination may appear in different places in the abdominal cavity.

If lying in a curved position, the individual sections (arrows) are close to each other, in contrast to the inflamed appendix that becomes more rigid and stretches to some extent.

Not infrequently strongly reflective structures (arrows) with an acoustic shadow are found, indicating inspissated feces.

As they are small and not calcified on CT, they are no true fecoliths and also do not predispose for appendicitis.

US images in this 15 year old boy show a normal compressible appendix with a large fecolith (arrows), producing a hard acoustic shadow.

The patient was symptom free at the time of the US examination, but he recalled four, one-day-lasting, self-limiting episodes of severe RLQ pain over the past nine months, suggestive for recurrent acute appendicitis. After appendectomy he had no more attacks.

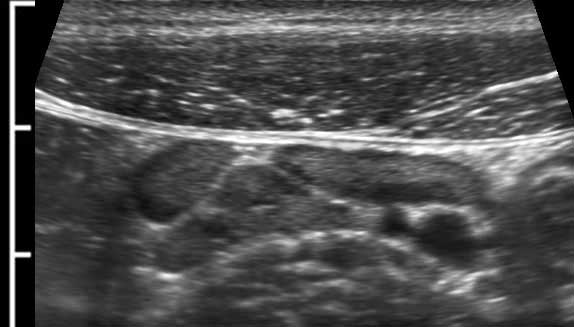

In children, the deep mucosa may show remarkable hypoechoic thickening due to lymphoid hyperplasia, which may also render the appendix less compressible.

This is a common finding in healthy kids, but in case of very prominent hyperplasia, a viral infection may be present.

Note the complete absence of inflamed fat.

Colon

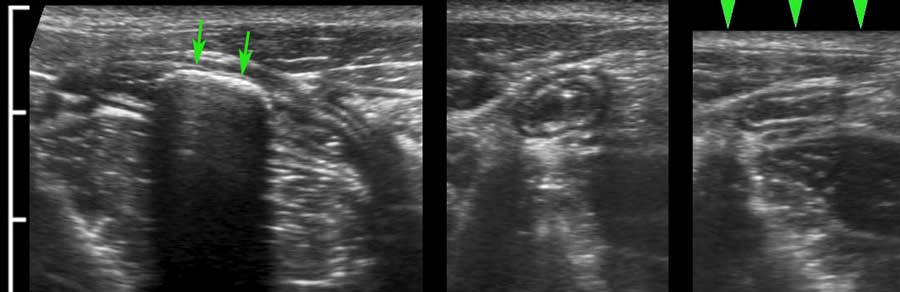

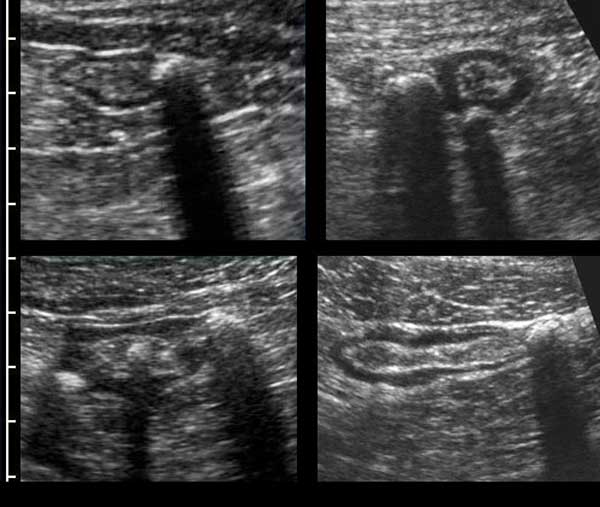

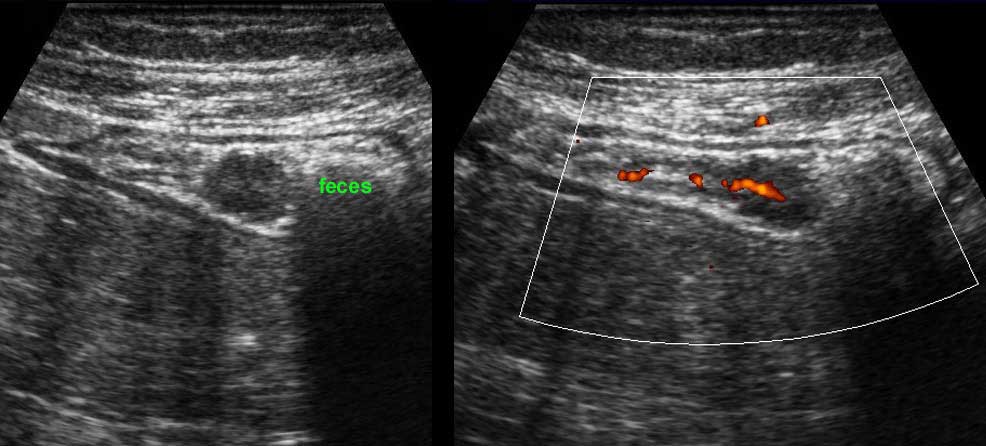

Longitudinal (left) and transverse (right) image of the empty sigmoid in a lean patient.

In the transverse image three areas of local thickening of the muscularis (arrowheads) represent the three teniae coli (arrowheads).

Normal colon filled with feces (left), during contraction (middle) and during relaxation and compression (right).

Normal colon wall thickness during compression is 3-4 mms.

Acoustic shadowing of the feces prevents US visualization of the posterior wall (left).

Colon is distinguished from small bowel by location, fecal contents, scarce peristalsis and a thick outer muscle layer with three tenia coli.

The muscularis of the sigmoid may considerably vary in thickness, mainly due to contraction.

Permanent thickening of the muscularis is associated with the development of diverticula (arrows).

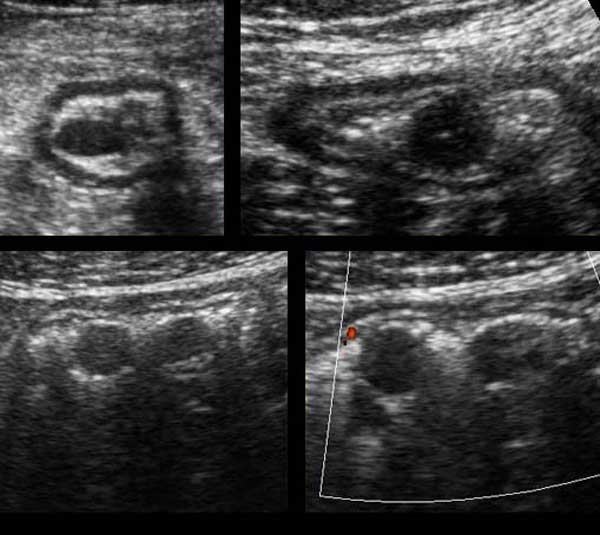

Sigmoid diverticulosis in four different patients.

Feces-filled diverticula are best visualized when the colon is contracted.

They present as bright reflective structures with an acoustic shadow on the outer contour of the colon.

Note the variable thickness of the muscularis in these four patients.

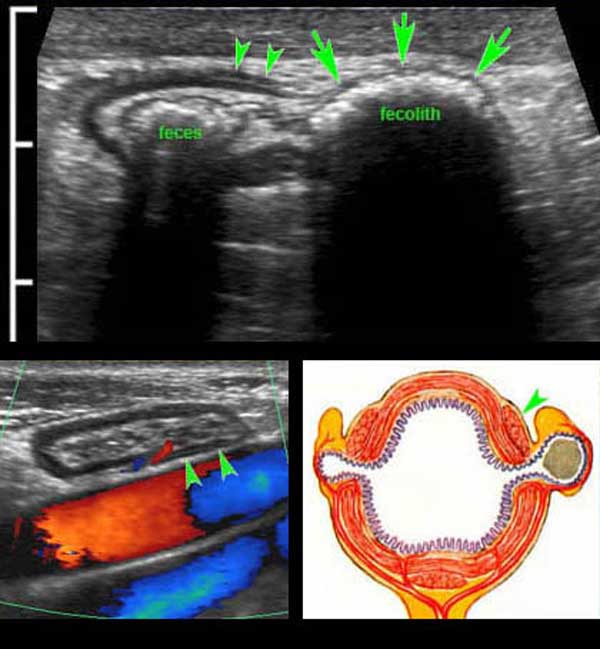

Detailed US image of sigmoid diverticulum in very lean 61-year old patient.

There is a little feces present in the sigmoid lumen and a large fecolith in the diverticulum (arrows).

Note the very thin wall of the diverticulum, consisting of herniated (sub)mucosa covered by a very thin serosa.

The herniation through the muscularis, invariably occurs at a weak spot where the vessels penetrate the circular muscle layer, immediately next to the tenia coli (arrowheads). These penetrating vessels are identified by color Doppler in another very lean patient (left under) and illustrated in the Netter image right under.

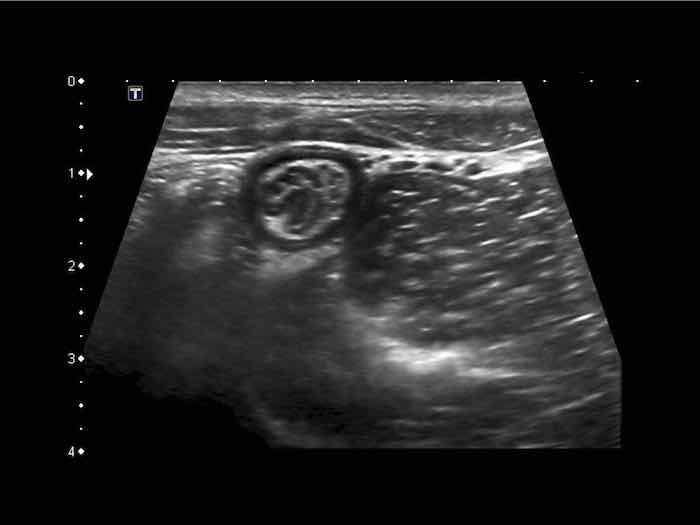

Undigested vegetables may incidentally appear as so-called “black feces” within the colonic lumen. These can be differentiated from colonic polyps by their edgy contours, lack of vascularity, their lack of adherence to the mucosa and their disappearance during follow-up.

Incidental finding of a round echolucent structure in the sigmoid lumen. This proved to be a vascularized polyp at color Doppler. Subsequent colonoscopy and histology confirmed a polypoid, tubulovillous adenoma. Colonoscopy found also three other adenomas, not detected by US.